Activists: Don’t Blow Another Opportunity on Homelessness

This story was produced as part of a larger project led by Jacob Pierce, a participant in the 2020 California Fellowship, about the health impacts of homelessness.

Other stories by Jacob Pierce:

Homeless-oriented housing aimed at saving lives and money

Disease, Dirty Needles: Santa Cruz County’s Other Health Crisis

An Overdose, New Services and Uncertainty on Homelessness

Santa Cruz County Fires: Meet the Climate Refugees

Environmentalist’s Take on the San Lorenzo River Homeless Camps

If Kicking Out the Homeless Doesn’t Work, What’s Next

Santa Cruz’s Homeless Die Much Younger Than Everyone Else. Why?

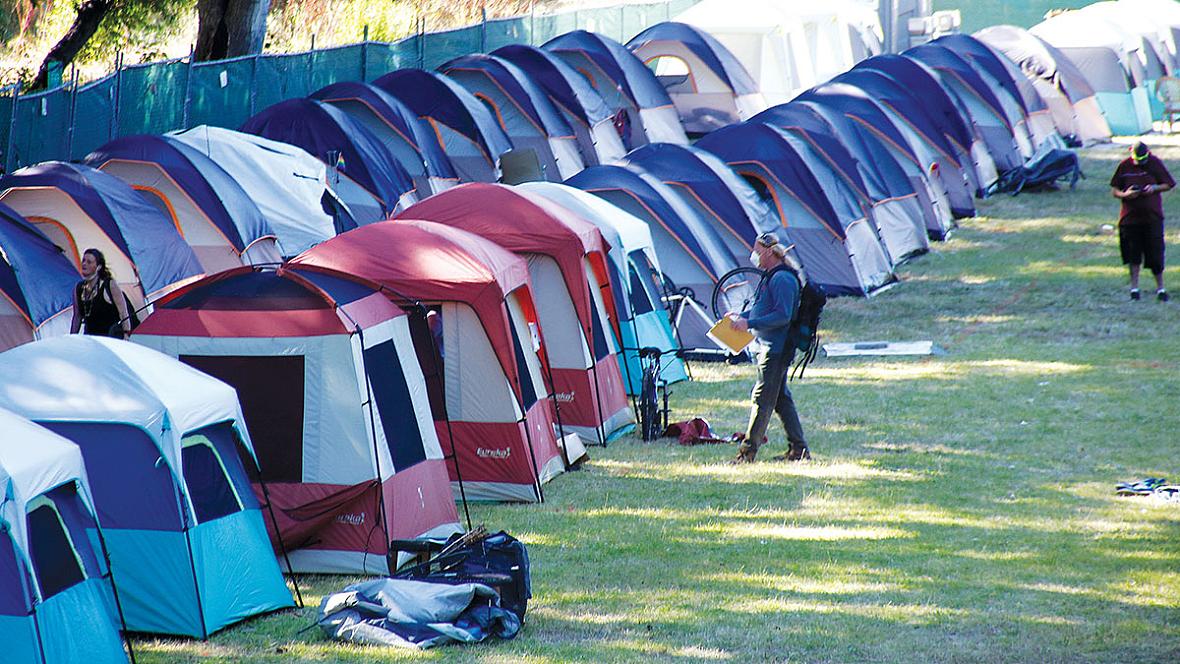

THE CITY AND COUNTY OF SANTA CRUZ HAVE PARTNERED IN A NEW MANAGED ENCAMPMENT IN SAN LORENZO PARK.

PHOTO: TARMO HANNULA

Joey Crottogini, manager of the Homeless Persons Health Project (HPHP), sees homeless patients all week at his small county-run clinic at the Housing Matters shelter campus in Harvey West. His staff treats patients for everything from infected wounds to their psychiatric needs.

Crottogini says the current Covid-19 pandemic poses a number of threats to the county’s homeless population. Many people living on the streets, for example, are medically vulnerable. They may not have a phone or a computer, limiting their access to up-to-date public health guidance. And when beds are available, some stay in shelters or other facilities, where social distancing guidelines could be difficult to enforce. (A cluster of Covid-19 cases temporarily closed a Watsonville shelter last month.) On top of all that, a history of stigma and discrimination against homeless individuals—combined with the limited ways for homeless people to access services—can make them reluctant to seek medical help, he says.

“The best way to prevent further outbreaks is to shelter in place,” he says. “That really creates a dilemma: How do you do that with a population that has no shelter?”

REPORTING OUT

The threat that the pandemic poses to Santa Cruz County’s homeless population is not totally unique. Every December, Crottogini works with HPHP Administrative Aide David Davis to put together a list of all the local homeless people who have died that year. They totaled 58 homeless deaths this past year. Crottogini says it’s likely an undercount. According to their findings, the individuals died at an average age of 53, 22 years younger than the average housed resident who died.

Lately, Crottogini has seen the pandemic shift the paradigm on homeless issues and people’s access to facilities in a way that makes him optimistic.

Suddenly, there are more portable toilets and hand-washing stations around Santa Cruz. There are managed homeless encampments, too, and government officials have handed out 180 state-funded motel vouchers to medically vulnerable homeless individuals, who now have places to stay for the foreseeable future. Crottogini adds that he had never seen the leaders from the city and county of Santa Cruz collaborate so well on homeless issues.

There’s also a highly anticipated report from a citizens’ group looking at homelessness. The report is finished and ready to go to the Santa Cruz City Council for review before its Aug. 11 meeting.

The council first formed the 13-member Community Advisory Committee on Homelessness (CACH) last year once rancor over the homeless issues reached a fever pitch. The city’s residents and council members were fighting about ideas, like transitional encampments and expansions of overnight parking zones.

The problem now is that some CACH members say that the council had a chance to take a big swing at ways to reenvision homeless services in the county, and they worry they’ve blown it.

“We missed that opportunity to present the council with something that was controversial,” says CACH member Rafa Sonnenfeld, one of five CACH members GT spoke with. “I felt like the CACH was created to deflect community pressure. We can be the dumb committee. They can blame us if we present something controversial, but we didn’t have the political courage to do that.”

Sonnenfeld stresses he does not disagree with anything in the report per se. He just thinks it could have been more ambitious.

He got some on-the-ground experience around the issues four months ago, volunteering with fellow CACH member Serge Kagno to manage a city-run encampment near the Kaiser Permanente Arena that lasted about 36 hours in the early days of the pandemic, while the city was still ironing out the details of its Covid-19 response.

Although the CACH unanimously signed off on the final report, Kagno and Sonnenfeld view the CACH’s mid-term report—which went to the City Council in February—as a purer distillation of the committee’s findings. The council took action on seven of those 22 recommendations in February.

Kagno, a homeless services consultant, and Sonnenfeld both wish the committee’s report had turned out more like the Santa Cruz County Civil Grand Jury report on homelessness. That report blasted government officials for their lack of leadership, electeds for their limited political will and the broader community for its disinterest in proven solutions. Kagno and Sonnenfeld say they had hoped the committee would pull together a rubric, laying out a variety of shelter options—weighing the pros, cons and various costs of each.

The two of them served on the Safe Sleep Sub-Committee with a few CACH members, including former Mayor Don Lane.

Lane, a longtime homeless advocate, shares some of the frustrations expressed by Sonnenfeld. But the pandemic created distractions both within the committee and across the community, he says, while also eating up time of city staffers, whom the committee members needed to have present every time they met. And at the end of the day, the committee had a deadline to meet.

“The report was the best we could do,” he says.

The final report, which was obtained by GT, recommends robust community engagement around homelessness, safe places to sleep and a new navigation center shelter campus.

Two Santa Cruz city staffers wrote the final CACH report with input from co-chairs Taj Leahy and Candice Elliot, who says the report pulls from a wide range of the committee’s meeting materials, as well as community input. She’s proud of the final result.

“What we passed is not watered down,” Elliot says. “It’s supposed to be a community assessment. It’s not a revolutionary group.”

CAMPING UP

If it sounds like a couple of the CACH members put high expectations on a 22-page document, it’s worth remembering that this is not the first local homeless-related document—nor was the Grand Jury report “Homelessness: Big Problem, Little Progress,” which came out last month.

The City Council already approved a report from a Homelessness Coordinating Committee back in 2017. At times, it has appeared that the city was better at approving plans than at acting on them.

But right now in this moment, Vice Mayor Donna Meyers says the city absolutely has the political will to start reducing homelessness, but she says the city may not make serious progress for 10 years. After five years, community members might be able to watch for signposts to monitor the ways in which progress is underway. “We’re going to be building out these systems for a long time—for at least a decade, and we really need to acknowledge the longevity,” she says.

Santa Cruz Mayor Justin Cummings says the CACH’s work has been instrumental in developing new models for homeless services.

Unhoused residents are moving into the new shelters and managed encampments. A fenced-off managed camp—a partnership between Santa Cruz city and county officials—opened this past week in San Lorenzo Park, for example. “We’re doing so much more than we were two years ago,” Cummings says, “and we’re doing even more, since Covid started.”

The discussion around homelessness can, at times, get touchy. Both committee member Kagno and co-chair Leahy say that much of the unstructured community feedback the committee got did not help to move the conversation forward in any meaningful way.

Leahy says that, at CACH meetings, most commenters from the public could be split into three camps: the anti-homeless NIMBYs, who oppose everything; the pro-homeless activists, who won’t compromise; and ordinary residents who simply want to see changes happen.

And Leahy—who doesn’t wish to name names here—says that sometimes it’s the homeless advocates that cause the most issues.

“Just support us; don’t poo-poo everything,” Leahy says. “It’s no wonder people are so disillusioned with politics. People are just tired of trying to get things through.”

This story was reported with support from the California Fellowship through the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism.

[This story was originally published by GoodTimes.]