Dallas Fire-Rescue to move forward with pilot blood transfusion program

The story was originally published in The Dallas Morning News with support from our 2023 Data Fellowship.

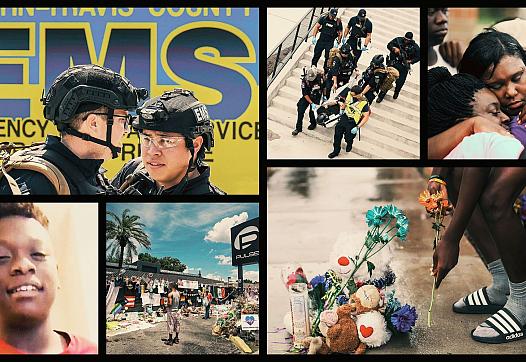

Austin-Travis County EMS medics and Austin firefighters worked on a victim of a motor vehicle accident in the back of an ambulance in May. Unlike in North Texas, paramedics in Austin have routinely carried blood to accident scenes for years.

Smiley N. Pool / Staff Photographer

Dallas Fire-Rescue plans to roll out a pilot program this summer that could benefit hundreds of patients with emergency bleeding from serious injuries across the city each year.

The fire department, which provides emergency medical services to the city of Dallas, intends to start carrying blood on some EMS vehicles in the coming months to speed access to transfusions for patients with life-threatening bleeding from shootings, stabbings, car crashes and other major injuries. That intervention could have benefitted as many as 674 patients treated by Dallas paramedics for serious injuries in 2023, according to a preliminary analysis of data that was presented to Dallas City Council’s public safety committee on Monday afternoon.

Medical research shows that mortality rates increase every minute for people with severe internal bleeding, sending many patients into irreversible shock before they reach a hospital. Decades of evidence from military conflicts, coupled with other medical research, shows that rapid blood transfusions administered by paramedics are safe and can save the lives of hemorrhaging patients who urgently need their blood replaced.

Such transfusions have been standard practice for years in other major Texas cities, including San Antonio and Austin, but they remain largely unavailable on ambulances across most of the Dallas-Fort Worth area. Nationally, a small but growing number of EMS providers have begun transfusing blood products in the field over the past five years.

Dallas Fire-Rescue is moving forward with the creation of its own blood program in response to Bleeding Out, a six-part investigation published by The Dallas Morning News and the San Antonio Express-News in November. The series found that tens of thousands of injured Americans bleed to death annually from potentially survivable injuries. The investigation highlighted the story of Malik Tyler, a 13-year-old boy who died from a potentially survivable gunshot wound in 2019 after being hit by a stray bullet while walking home with friends in his Pleasant Grove neighborhood.

The analysis of Dallas Fire-Rescue trauma calls found that many were concentrated in the downtown area, as well as large swaths of southeast and southwest Dallas, according to a heat map included in the presentation.

For many years, paramedics in Dallas and the rest of the country did not have access to blood products, which were typically only available during air medical transports and at trauma centers. Instead, they transported hemorrhaging patients as quickly as possible with only a limited set of tools: direct pressure and tourniquets, which can slow some types of bleeding, and saline, which replaces lost fluids.

None of those interventions are effective for treating severe internal bleeding, which kills many patients within the first half-hour after an injury — a quick timeline for patients in major cities and rural areas alike. Dr. S. Marshal Isaacs, the fire department’s chief medical director, said during the public safety meeting that saline lacks oxygen, which is crucial for keeping vital organs alive, and other components of blood that help stop bleeding.

For its blood program, Dallas Fire-Rescue is in talks with Parkland Health about potentially partnering with the Level I trauma center. Parkland representatives are considering providing blood to EMS supervisors who respond directly to major injuries that often result in serious bleeding. If the partnership moves forward, the blood would be stored in coolers and monitored to ensure it stayed within the correct temperature range. Unused units would be exchanged for fresh ones at the hospital before expiration to prevent waste, Isaacs said.

A similar system has facilitated more than 1,300 prehospital transfusions by the San Antonio Fire Department since 2018.

If Dallas Fire-Rescue finalizes a partnership with a blood supplier by spring, the pilot would launch in late summer. Isaacs said that additional analysis of calls for service will help the department focus on areas of the city where the most lives could be saved.

The benefits of the program could extend beyond patients with major injuries. The fire department’s presentation noted that patients who are hemorrhaging from medical conditions, such as gastrointestinal bleeds or pregnancy complications, could also receive prehospital transfusions.

Dallas Fire-Rescue’s blood program is being developed alongside another pilot at the North Central Texas Trauma Regional Advisory Council, which works with EMS providers across the region. Last year, representatives from the trauma council told The News that it intends to support five more EMS providers across D-FW in carrying blood products by the end of this year, particularly in areas where patients face longer transport times to major trauma centers.

“What we know is that blood transfusions initiated in the field can save lives — especially when the time it takes to get a patient and transport them to the trauma center exceeds 30 minutes,” Isaacs said.

CLARIFICATION, 4:41 p.m., Feb. 13, 2024: An earlier version of this story said Parkland Health planned to provide blood for Dallas Fire-Rescue’s pilot transfusion program, based on comments made at a public meeting. Parkland is still in ongoing discussions with DFR about whether it will provide blood for the program.