Why so many Americans bleed to death after a traumatic injury

The story was originally published by the The Dallas Morning News with support from our 2022 National Fellowship.

Malik Tyler was bleeding to death.

On a warm June evening four years ago, the 13-year-old was walking home with his friends after buying snacks from Adams Food Mart in southeast Dallas when they heard gunshots.

One boy ran back to the store while Malik and his other friend sprinted down the street to their families’ apartments. Outside the complex, Malik asked his friend if he had been shot.

He lifted up his shirt. There was blood on his torso.

The bullet that hit Malik in the back had fractured a rib and pierced his right lung, medical records show.

The friend ran for help. A security guard and Malik’s mother, Tina Sanders, heard the shots and sprinted to Malik, who had collapsed.

Tina, who had worked as a certified nursing assistant and a dialysis technician, found her son’s wound. Even in her panic, she instinctively knew he was bleeding internally into his chest, drowning in his own blood.

“Breathe, Malik. Breathe, Malik. Come on, Malik,” she sobbed in the background of a 911 call.

By the time Malik made it to Baylor University Medical Center, an estimated 36 minutes had passed since he was shot. By then, so much blood had pooled in his chest and lungs that it was likely impossible for him to breathe, medical records show. His organs, starved of oxygen, were failing.

Doctors and nurses pumped blood into Malik, desperately trying to replace what he’d lost.

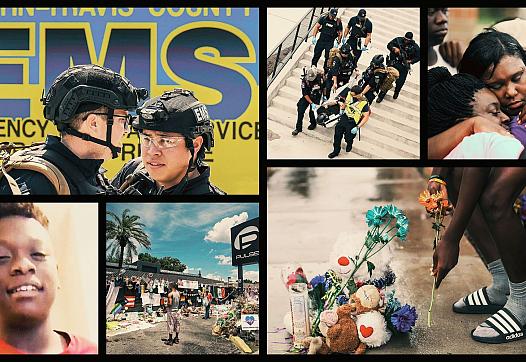

Tina Sanders (center), the mother of Malik Tyler, hugged friends and family during a vigil for Malik on June 5, 2019, near the scene where the 13-year-old was fatally shot in Dallas. Malik bled for about 20 minutes before paramedics arrived, death records indicate. Had Dallas Fire-Rescue paramedics been equipped with blood that day, or if Malik had been shot closer to a trauma hospital, the outcome may have been different.

File Photo / Staff

Ultimately he lost about as much blood as the average adult body contains — an estimated 5,000 milliliters. The transfusions came too late, medical experts who later reviewed his case said.

Malik was pronounced dead at 8:07 p.m., about an hour after he was shot.

The rising eighth-grader at the Young Men’s Leadership Academy at Fred F. Florence Middle School, who loved sports and video games and volunteered at a day care at his apartments, might have lived if the transfusions and control of his bleeding had come sooner, two experts who reviewed his autopsy said.

Malik, an incoming eighth-grader at the Young Men’s Leadership Academy at Fred Florence Middle School, was fatally shot near an intersection that had been problematic for years.

Family photo

Across the U.S., deaths like Malik’s unfold with grim regularity after shootings, car wrecks, falls and other accidents. Yet they don’t have to. A two-year investigation by The Dallas Morning News and the San Antonio Express-News has found dozens of deaths each day, from rural towns in Texas to major cities on both coasts, could potentially be prevented with faster access to blood.

After more than 140 interviews and reviews of hundreds of medical journal articles, The News and Express-News found that the vast majority of emergency medical providers — not just in Dallas and across Texas, but nationwide — are unequipped and underfunded, leaving them unprepared to fully treat patients with severe internal bleeding. Across the country, bleeding patients receive drastically different care depending on where they are injured and the emergency providers who treat them, our investigation found.

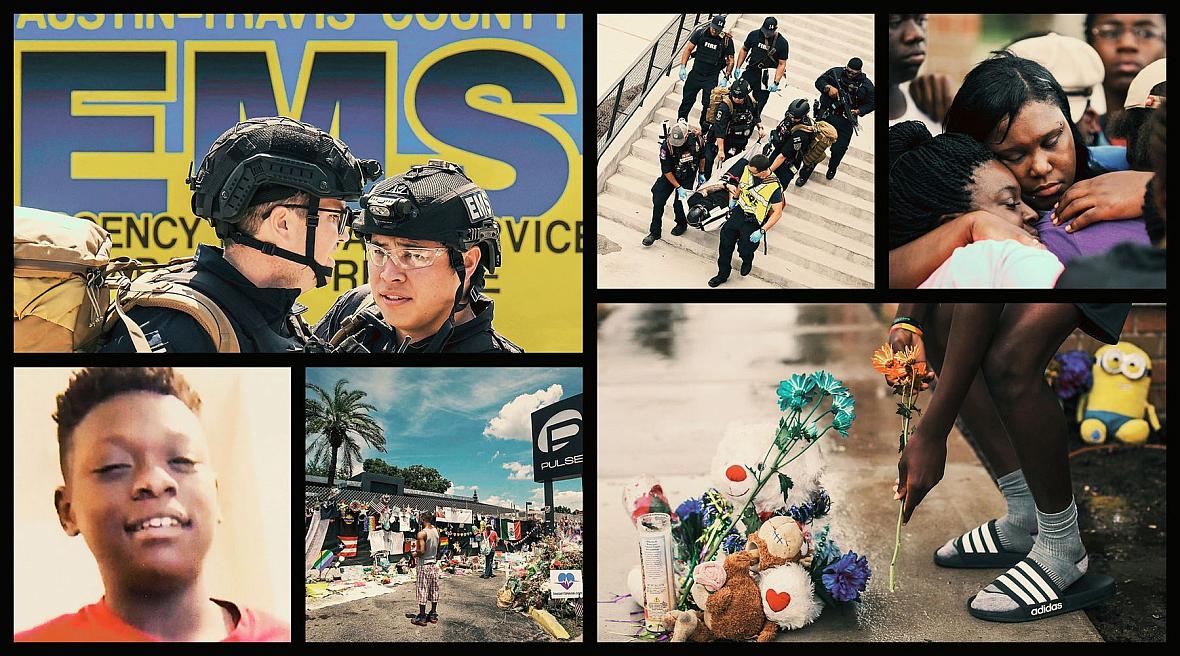

The consequences are dire: Traumatic injury is the top killer of children and adults under 45, far outstripping cancer and heart disease as a leading cause of premature death. In 2020, traumatic injury killed at alarming rates, claiming an American about every 3½ minutes, a Texan every 42 minutes and a Dallas County resident every 7½ hours, according to the most recent data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. No one is immune, regardless of age, race or socioeconomic status.

Each year, that translates to as many as 31,000 people bleeding to death from injuries they could have survived, researchers estimate. That’s the number of fans that would fill American Airlines Center during a Dallas Mavericks game 1½ times over.

“This is a public health disaster, and it’s been going on at least since the ’60s,” said Dr. John Holcomb, a trauma surgeon with the University of Alabama at Birmingham and leading expert on preventable trauma deaths.

For years, awareness of these deaths has been mostly confined to medical journals and discussions within the medical community, leaving the general public largely uninformed about the extent of the epidemic.

The news organizations’ investigation, which included interviews with dozens of physicians across the country, found trauma specialists are acutely aware that many patients are dying needlessly.

At its core, the solution is straightforward: If paramedics widely carried blood, as military medics have done for years, tens of thousands of lives could be spared annually. But the country’s fragmented health care system does not allow for an easy fix.

That crucial gap in care is a symptom of a larger problem.

For decades, despite repeated pleas from specialists, the federal government has not prioritized or properly invested in the plight of injured Americans, dozens of medical professionals and researchers said. Again and again, they have implored Congress to increase funds for research that could help save more lives. When lawmakers learned of the high rates of potentially preventable injury deaths at a U.S. House hearing in 2016, they failed to act, even as the military took steps years ago that have slashed mortality rates for wounded troops, our investigation revealed.

In the meantime, paramedics and doctors continue to watch helplessly as, day after day, patients like Malik die, despite their best efforts to save them.

“It’s like having nine 9/11s every year,” said Dr. Philip Spinella, a preeminent expert on trauma-related bleeding at the University of Pittsburgh. “And we’re doing nothing about it.”

INSIDE THE BLEEDING BODY

When someone is bleeding to death, it sets off a cascade of complex but predictable physiological reactions inside the body.

As cells become starved of oxygen, they overproduce lactic acid, impairing the ability of blood to clot. The heart works harder and the pulse skyrockets. The body diverts what blood remains away from the limbs and toward the heart and brain. The skin grows pale and clammy as the body’s core temperature plummets.

If lost blood is not quickly replaced, tissue begins to die and vital organs sustain permanent damage. These fundamental breakdowns within the body create a self-perpetuating cycle, signaling that death is near.

“What’s really difficult for people to get their minds around is this idea that trauma or injury should be thought of like a disease,” said Dr. Barbara Gaines, chief of pediatric surgery at UT Southwestern Medical Center. “It is an acute disruption of the body that happens, and it could happen through a fall, or it could happen through a car crash, or at the end of a bullet.”

For the most severely injured patients — especially those with internal bleeding like Malik’s that cannot be treated with tourniquets — the odds are bleak.

Mortality rates increase with each minute that passes, especially within the first half-hour, when severe bleeding deaths peak, according to research. That’s before many patients can make it to a hospital, let alone receive transfusions to replace what blood was lost.

Too often, people bleed out because our nation’s system for treating patients before they get to a hospital is too slow to save them — just as it was too slow to save Malik.

As Tina held her son in her arms, she knew the help he needed was taking too long. Responding police officers administered CPR, but she did not believe it would do any good for Malik’s internal bleeding.

“Had he got to the hospital on time … he probably would have made it,” she said.

PREVENTABLE TRAUMA DEATHS

Over the past decade, researchers from Texas, Alabama and Florida have studied autopsies of injured patients to better understand preventable deaths. While estimates vary across about a dozen studies, these reviews indicate that as many as 1 in 3 trauma victims could recover from their injuries with faster access to high-quality medical care.

The most common cause of preventable death is when patients bleed out before they can be treated, just as Malik did, the studies show.

Holcomb, who previously served as a commander at the U.S. Army Institute of Surgical Research in San Antonio, has researched preventable trauma deaths for more than a decade. During his long military career, he studied bleeding deaths and helped pioneer advancements in the treatment of wounded soldiers. When he retired from active duty in 2008, he took those lessons with him to civilian medicine.

In one study, he reviewed more than 1,800 trauma deaths in 2014 in Texas’ Harris County, which includes Houston. It found that 36% of deaths resulted from potentially survivable wounds, with 1 in 6 deaths caused by uncontrolled bleeding. Nearly half of hemorrhaging victims could have survived their injuries, his research found.

When another research group from George Washington University studied the 2016 shooting at the Pulse nightclub in Orlando, Fla., they found 16 of the 49 deaths involved potentially survivable wounds.

People visit a makeshift memorial outside the Pulse nightclub in Orlando, Fla., the day before the one-month anniversary of a mass shooting at the club. On June 12, 2016, a gunman killed 49 people and injured 53 others. Of those who died, researchers say 16 involved potentially survivable wounds.

File Photo / The Associated Press

These studies echo the work of military researchers, who for years have examined combat deaths from bleeding and other preventable causes and taken steps to reduce them.

During the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, military medical teams evacuated wounded troops faster, increased tourniquet use and administered blood on the way to the hospital. Military leaders made these changes throughout the 2000s based on rigorous data collection, including performing autopsies on every combat fatality and standardizing treatment across the military.

From 2005 to 2013, mortality rates for troops serving in Afghanistan fell by nearly 50%, even as the severity of injuries increased. One Army special operations unit, the 75th Ranger Regiment, virtually eliminated prehospital preventable trauma fatalities during their missions in Iraq and Afghanistan.

No such overhaul has happened in U.S. health care, and efforts have not been made to broadly adopt the military’s best practices, particularly before patients reach a hospital.

Despite pleas to elected officials for more research funding from some of the nation’s most respected researchers, mortality rates remain stubbornly high for Americans with traumatic bleeding.

Hemorrhaging patients need a higher level of care, especially quicker access to blood, said Dr. Zaffer Qasim, a critical care physician with the University of Pennsylvania Health System.

“It’s like a coin flip whether they survive or not, because they’re so far into the process of dying,” he said. “Sometimes you just can’t reverse it, no matter how fast you are once they get to the hospital.”

In 2019, the year Malik died, an analysis by researchers from the University of Alabama at Birmingham of EMS data for more than 3 million trauma patients across the country found less than 1% received blood products of any kind on the way to the hospital, even when they displayed clear warning signs of bleeding out.

Another study of patient data from that year by the UAB team estimated 50,000 to 300,000 injured patients had the hallmarks of major blood loss before they arrived at a hospital, indicating they likely needed blood.

Earlier this year, three medical associations, including the American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma, published a joint statement showing their support for giving blood to hemorrhaging patients on the way to the hospital whenever possible.

The bullet that struck Malik was meant for someone else, testimony from the trial of the man convicted of his death shows. The teen was caught in the crossfire at a street corner known for drug deals and gang violence. Malik, who had just started his summer break, suffered the consequences.

Death records indicate Malik bled for about 20 minutes before paramedics arrived, a crucial delay for a rapidly deteriorating patient. Had Dallas Fire-Rescue paramedics been equipped with blood that day, or if Malik had been shot closer to a trauma hospital, the outcome may have been different, Holcomb, the UAB trauma surgeon, said.

Gaines, who separately reviewed Malik’s records while she was the pediatric surgery program director at UPMC Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh, arrived at a similar conclusion.

“Anatomically, his injuries were fixable,” Holcomb said, adding the boy would have had a better chance of survival in a combat zone, where military medics are armed with blood.

In a statement to The News in October, Dallas Fire-Rescue did not comment on the specifics of Malik’s case and said it would not “speculate on the survivability of any one patient.”

The department added, however, that it intends to move forward with a pilot prehospital blood transfusion program, in partnership with Parkland Health. Dr. S. Marshal Isaacs, Dallas Fire-Rescue’s medical director, said he expected the pilot would launch during the first half of next year, starting in an area of the city that sees a high volume of traumatic injuries. The program’s time frame and success will depend on availability in the blood supply, he said.

The announcement of the pilot program came after repeated rounds of questions from The News since the summer of 2022 about ways to improve care for bleeding patients. Initially, fire department leaders were noncommittal about when they might be able to support a prehospital blood program.

“We see this as another way that we could potentially save more lives,” Isaacs said in late October.

A ‘NEGLECTED DISEASE’

The federal government does not study or track preventable trauma deaths. The scope of potentially avoidable deaths came to light only through the work of Holcomb and other researchers intent on helping their patients.

These deaths are part of what some medical experts characterize as a legacy of inaction by federal lawmakers, who have long been alerted that shortcomings in emergency health systems are costing unnecessary lives.

For decades, medical specialists have argued that, as a leading cause of death, traumatic injury should receive significant federal money for research and prevention, as is allocated to cancer and heart disease.

Independent reviews have found the National Institutes of Health, the world’s single largest source of public funding for medical research, devoted an estimated $639 million to trauma-related studies in 2018, less than 2% of its budget. That year, cancer received an estimated $6.3 billion.

At least a dozen times, trauma doctors have made the case for more resources — in reports issued over nearly six decades, during meetings at the NIH in 2009 and at congressional hearings, including in 2016.

Our reporting found that as early as 1966, the National Academy of Sciences and the National Research Council called unintentional injury the “neglected disease of modern society.” The report captured the attention of federal lawmakers and became a landmark document for the medical community.

The report noted that, unlike cancer, there was no NIH institute for injury. Ambulance services were rife with poorly trained attendants. Morticians routinely transported patients by hearse. Experts returning from combat zones in Korea and Vietnam said soldiers had a better chance of survival than people hurt on the average U.S. city street.

The findings led to the birth of modern emergency medical services. In 1973, a galvanized Congress appropriated more than $150 million to create systems across the country.

Interest in taking other steps outlined in the report soon faded. The NIH institute for trauma never materialized. In the 1980s, Congress ended direct federal funding for emergency medical providers. Instead, states received grants that could be used for health services beyond just EMS. The competition for funds left the field under-resourced, a problem that persists today, experts say.

Over the next three decades, medical experts publicly issued five more reports between 1985 and 2007 calling for greater federal attention to the nation’s trauma epidemic, with varying degrees of success.

By 2015, medical researchers at the National Academies were ready to try again, this time with support from the departments of Defense, Homeland Security and Transportation and a member of the National Security Council. They formed a committee to study lessons from treating injured troops in Iraq and Afghanistan and other conflicts and examined how the protocols could be applied to civilian trauma medicine.

Many of the systemic problems identified in the 1966 report still existed almost 50 years later, said Jorie Klein, a committee member who was then director of the Parkland trauma program. Instead of a national trauma system that ensured advanced care for all patients, the U.S. had a “frayed patchwork quilt,” Klein wrote in a statement submitted to federal lawmakers.

“This committee is by no means the first group to suggest a number of these changes,” the committee wrote in its 490-page report. “Yet too many of the prior calls for consolidated leadership, strong systemic designs and clear lines of responsibility have not been heeded.”

The committee also found that, despite dramatic surgical advancements, many injured patients could not access lifesaving treatment. No one federal agency was responsible for oversight of the nation’s emergency health care systems. Existing regulatory bodies lacked funding and authority, its report said.

There were likely 200,000 to 300,000 potentially avoidable deaths of injured Americans over a 10-year period — and that was a conservative estimate, according to a study the report cited. Care could be improved if military and civilian trauma teams shared data and resources, the committee found.

“There was a lot of strong feeling in this committee about, for Pete’s sake, let’s not put it back on the shelf,” said Dr. Donald Berwick, a former administrator of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services who chaired the National Academies committee. “The clinical community is mobilized — they really want to do something about this. But getting the government’s attention is very hard.”

In its report, the committee issued nearly a dozen recommendations and called for the elimination of preventable trauma deaths. The highest levels of government needed to work together and be accountable for the changes: the White House, Congress and the departments of Defense and Health and Human Services, the report said.

“No level of government below the White House has the leverage to achieve this level of collaboration, and thereby to avert needless deaths and disability due to suboptimal trauma care,” the report said.

Ironically, two mass shootings bookended the report’s release in June 2016 — first in Orlando, then in Dallas the next month.

After a sniper shot police officers and bystanders in Dallas on July 7 at a downtown protest, dozens of officers crowded into the trauma area at Klein’s own Parkland hospital. Klein and her colleagues rushed to triage seven of the victims, some of whom arrived in the back of police cars.

Dallas police officers saluted outside Parkland Hospital as the bodies of three fallen officers were taken from the hospital the early on the morning of July 8, 2016, after a mass shooting the previous evening in downtown Dallas. Jorie Klein, the director of the hospital’s trauma program, was a member of a committee to study lessons from treating troops in Iraq and Afghanistan and how the protocols could be applied to civilian trauma medicine.

File Photo / Staff

By the end of the night, three had died. Outside the hospital, as the medical examiner’s office removed the bodies of their fallen colleagues, a line of officers stood in salute.

In an instant, Klein’s city had turned into a war zone. This could happen anywhere, she realized. Everyone needed to be ready. The reforms proposed in the report could help make that happen, she said recently in an interview.

That fall, Tammy Duckworth — an Illinois congresswoman and former Army National Guard pilot who lost both of her legs in combat — filed a bill to establish a federal task force on eliminating preventable trauma deaths and to create national trauma care standards. Her bill was sent to committee that October but never received a vote.

Instead, by the end of 2016, Congress had allocated an additional $1.8 billion in funding for cancer research, as part of a sweeping initiative to improve outcomes spearheaded by then-Vice President Joe Biden. Six years later, in February 2022, President Biden’s administration renewed the White House’s involvement with that program, setting the goal of cutting cancer death rates in half over the next 25 years.

GOVERNMENT GRIDLOCK

In the last decade, the federal government has taken smaller steps to improve trauma care. Some experts say they do not go far enough.

In 2012, the NIH created an office dedicated to emergency medical research. Consisting of just one person, the office lacks a research budget. Its purpose is to help trauma researchers navigate the sprawling agency to apply for grant money.

The NIH administers most of its $48 billion annual budget through 27 institutes and centers that are dedicated to particular diseases or bodily systems. Institutes receive far more grant applications than they can fund, so they overwhelmingly invest in work that aligns with their specialized mission, said Dr. Jeremy Brown, who has led the Office of Emergency Care Research since its inception.

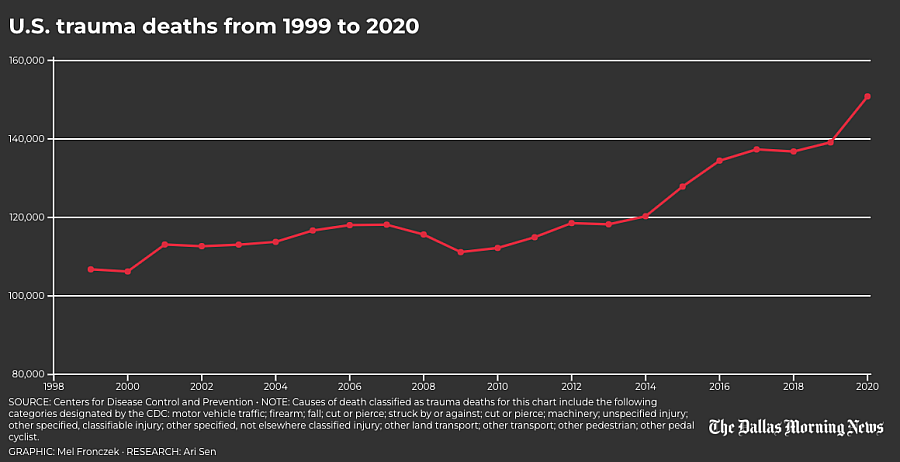

Austin-Travis County EMS medics join Austin police and Austin firefighters in a joint rescue task force/counter-assault strike team, or CAST, training in May. The program enables paramedics to provide advanced care under the protection of specially trained officers during an active attack situation. The goal is to get medical help to victims quickly and while the incident is still active.

Smiley N. Pool/Staff Photographer

Austin-Travis County EMS medics prepare to take part in an active shooter training scenario at Q2 Stadium in North Austin. Every year, the Austin Police Department offers such training for their counter assault strike teams.

Smiley N. Pool/Staff Photographer

Austin police move in formation to secure the scene during active shooter training. In Austin, a rescue task force is predeployed downtown on Fridays and Saturdays and during special events such as the annual South by Southwest festival. This allows rescue personnel to 'access patients that will normally be inaccessible by an ambulance or a fire truck or a police car,' Austin-Travis County EMS Commander Craig Smith said.

Smiley N. Pool/Staff Photographer

Austin-Travis County EMS medics take part in an active shooter training. They are part of the medical support for the Austin Police Department's Counter Assault Strike team, a unit that specializes in active attack response, such as a mass knife attack, mass shooting or mass vehicle attack.

Smiley N. Pool/Staff Photographer

Austin-Travis County EMS medics triage with their police and fire department colleagues during an active shooter training. The Austin Police Department trains 60 officers at a time in active attack response.

Smiley N. Pool/Staff Photographer

A supervisor holds a training band worn by a role player to identify a gunshot wound during the training. The small hole at left represents an entry wound, and the larger hole represents an exit wound on a gunshot victim

Smiley N. Pool/Staff Photographer

An Austin police officer secures a shooting suspect as EMS and fire personnel finish evacuating victims during the training.

Smiley N. Pool/Staff Photographer

An Austin paramedic and a police officer transport a victim to an ambulance during the training.

Smiley N. Pool/Staff Photographer

Police provide security for ambulances staged to evacuate victims. 'Stop the killing, stop the dying, and then rapid casualty evacuation is our mantra," said Smith, the EMS commander. 'That's what we're all working towards, the same goal. The CAST officers allow us, as paramedics, to have our own security. So we don't have to wait.'

Smiley N. Pool/Staff Photographer

Fire, EMS and. police evacuate a victim from the Austin active-shooter scenario

Smiley N. Pool/Staff Photographer

Police provide security as firefighters and paramedics load a victim for transport, 'If I'm on an RTF or I have CAST officers with me, I can go straight to the casualty. And that's our goal,' Smith said. 'Our goal is not to engage the shooter. We're not a contact team. We are medical asset with built-in security.'

Smiley N. Pool/Staff Photographer

Brown’s office tried to bring more attention to trauma research in 2017 by hosting a conference with the Department of Defense, which researches injuries sustained from combat. But NIH cannot unilaterally establish a separate institute for trauma or increase the field’s share of research dollars, he said. Only Congress can.

“You can imagine, in the current climate, how well funding a new government agency is going to go down,” he said.

Through a spokesperson, NIH executive leadership declined repeated interview requests to discuss how the agency prioritizes trauma as a public health issue. In a statement to The News in June, the agency said almost all of its institutes and centers fund some trauma studies, based on applications from outside researchers. NIH does not specifically budget by disease category or track funding for trauma research.

However, because traumatic injury doesn’t easily fit under any one NIH institute category, it often still falls through the cracks, Brown said.

In 2015, the White House promoted a “Stop the Bleed” campaign to train bystanders on the use of direct pressure and tourniquets. While tourniquets can stop bleeding from limbs, they do nothing for chest or abdominal wounds, trauma specialists say.

That’s why tourniquets alone cannot solve the problem, said Dr. E. Reed Smith, an emergency medicine and EMS physician at George Washington University who has studied preventable deaths in mass shootings. Most preventable bleeding deaths involve internal, not external, hemorrhage, he said.

“It’s not enough,” he said.

In 2019, Congress approved a grant program that embeds military medical specialists in U.S. trauma hospitals. Rep. Michael Burgess, who authored the legislation and represents Texas’ 26th congressional district that includes parts of Tarrant and Denton counties, said he has to fight for even small amounts of funding. Congress appropriated $4 million for the program in 2022.

Burgess, a retired doctor, expressed skepticism about the effectiveness of a new NIH center for trauma, given the performance of national public health institutions in recent years.

In interviews The News conducted with dozens of physicians from across the country who specialize in trauma and emergency medicine, explanations varied for why trauma deaths do not command greater attention or resources.

Some theorized that people do not consider the possibility of becoming injured to the same degree that they might worry about getting cancer. Others worried that the field of trauma lacks the same kind of marketing and patient advocacy that catapulted autism and ALS into the public lexicon in the past decade.

Two of the main causes of trauma in the U.S. — cars and guns — are also highly politicized and influenced by powerful lobbying interests.

Because injuries can result from external accidents, including misbehavior, there can be the misconception that trauma victims are unsympathetic, said Danielle Tatum, a research director at Tulane University School of Medicine.

Sometimes, they are blamed for getting hurt.

“We’re all human. Humans are going to make mistakes,” said Shelli Stephens-Stidham, a consultant for the Safe States Alliance, a national injury prevention group.

MAKING BLOOD AVAILABLE

Given the lack of major government action on traumatic injury, a group of advocates from around the country is working on solutions that it can control, including removing barriers to delivering blood more quickly to patients like Malik.

In the U.S., where there are more than 23,000 emergency medical agencies, only about 100 ground ambulance services have blood on hand, trauma advocates have found in recent surveys. While most air ambulance companies carry blood products, they treat only a small fraction of injured patients.

Blood is a costly, limited resource, and most emergency medical providers lack relationships with blood banks. They also face regulatory and logistical hurdles, like maintaining blood refrigeration temperatures in the field and creating a system where unused units do not go to waste.

The Prehospital Blood Transfusion Initiative Coalition — which includes doctors, paramedics and blood banking specialists — is focusing on two core issues that prevent many EMS providers from carrying blood: their inability to bill insurers for the cost of the blood and the rules in some states that prevent paramedics from starting transfusions.

Under rules set by Congress for the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, EMS providers only receive reimbursements for services if they transport a patient to a hospital. While payments take into account distance and level of care provided, they are not itemized. Experts say the formula does not fully cover the expenses of an ambulance service, including costly items like blood.

The group hopes to present recommendations to Congress and the National Association of State EMS Officials next year. Their goal is that every patient with major bleeding — including the injured and those hemorrhaging from medical complications — will receive blood if they need it.

“We cannot get to zero preventable deaths if we don’t do this,” Holcomb said.

Randi Schaefer, a member of the coalition’s steering committee and retired Army combat nurse, saw the difference that early access to blood could make for troops with grievous wounds during her deployments to Iraq.

She thinks about bleeding out like drowning: The body desperately needs oxygen, and the clock is ticking.

Heart attack patients don’t have their treatment delayed until they get to a hospital, she said. Bleeding patients shouldn’t have to wait, either.

Tina and her five other children miss Malik — the boy who could always bring a smile to their faces, who protected his little sister and encouraged the other children at the day care where he volunteered every day after school.

Tina hopes his death can serve as an impetus for improving care for other patients moving forward.

“The world needs to know,” she said. “We need to do better to save somebody else. We can’t save him, but we can save somebody else.”

A child who attended the day care center at the Sterlingshire Apartments placed a flower on a memorial near where Malik was killed. Malik visited the day care often and would help the staff with tasks after the children left.

2019 File Photo / Staff