Here’s one Orange County family’s story of generational gang violence. Can the city’s latest efforts break the cycle?

Denisse Salazar wrote this story, part of a series, while participating in the USC Center for Health Journalism’s California Fellowship.

Hugo Secundino, 42, holds a weathered picture of his deceased son Angel, one of the only photos he has of the boy who was gunned down in gang violence at age 14 a little more than a decade ago. (Photo by Mindy Schauer, Orange County Register/SCNG)

Hugo Secundino picked up his 10-year-old granddaughter for a recent afternoon visit to the sprawling Santa Ana Cemetery and the grave of her father.

A little more than a decade ago, Secundino’s son was gunned down in gang warfare at the age of 14, eight months before his daughter was born.

They arranged roses, carnations and daisies near a small metal plaque bearing Angel Secundino’s name. His family had a headstone placed over the grave. But it has long since been smashed to pieces, presumably by street gang enemies, a pointed reminder of the violence that consumed the boy and the lingering pain that has haunted relatives since his death in 2006.

As they knelt on the lush turf, Hugo Secundino kissed the girl on the forehead, and gave her a tight, protective hug.

The headlines generated by Angel’s killing faded quickly. But his death links four generations still struggling with the regrets, emotional wreckage and fear that come when loved ones become immersed in the gang lifestyle.

Losing his son to street violence “destroyed my heart,” said Hugo Secundino, now 42.

Secundino, a construction worker who didn’t finish high school, blames himself for paying too little attention to Angel during his formative years. He said his son followed an uncle’s footsteps into a Santa Ana gang.

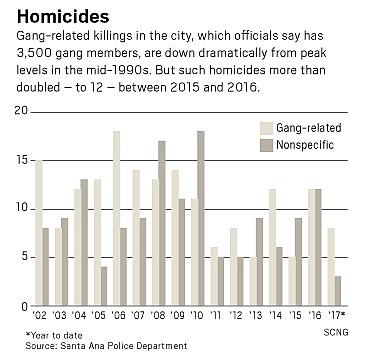

Angel’s age and his murder on a Sunday afternoon a week before Christmas – by a group of teenagers as young as 14 – shook the city, despite its long history of gang shootings. His death came amid a spike of 18 gang-related homicides in a single year, which remains a 20-year high for Santa Ana, and helped prompt the creation of a city commission charged with seeking better ways to help children steer clear of gangs.

A decade later, the panel is gone, a victim of budget cuts during the Great Recession.

After gang homicides more than doubled – to 12 – between 2015 and 2016, elected leaders are again re-examining programs to aid children like Angel.

A series of community forums organized by Mayor Pro Tem Michele Martinez, who grew up in a city home she described as a “crack house” with a drug-addicted mother, is seeking to improve the coordination and effectiveness of community programs aimed at aiding at-risk children and their families. The city also has created a new position intended to serve as a bilingual, one-stop shop for children and families searching for assistance with counseling, after-school and sports programs and mentoring help, as well as identifying gaps in services and evaluating which efforts are most effective.

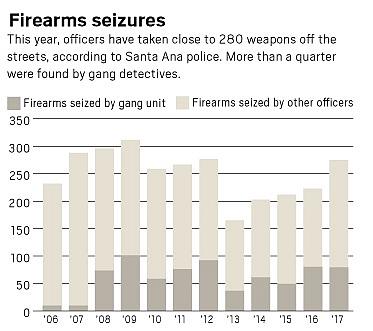

The city’s acting police chief, David Valentin, has shifted officers into a stepped-up, seven-day-a-week gang-suppression effort that includes getting firearms off the street. Valentin also grew up in an area of the city known for gang violence and as a teen lost a close friend to a drive-by shooting. He said he is encouraging officers to get out of their patrol cars and create positive role models by kicking around a soccer ball or casually chatting one-on-one with both children and adults.

What the latest efforts in Santa Ana will achieve remains to be seen. Some seek to revive and expand long-standing gang-reduction programs.

But the efforts also involve a new emphasis on nurturing broader community involvement in identifying what needs to be done and bolstering efforts to understand and address the individual challenges and trauma facing children at home, in school or their neighborhood.

The Santa Ana Unified School District – one of the largest in the state and the largest district in Orange County – has expanded mental health services over the past two years to help students struggling with trauma. Officials say the beefed-up mental health programs have connected more students who are acting out, disengaged or have experienced violence in the community or at home with therapists who try to identify the root causes of the behavior.

“One of the goals of therapists is to identify the mental health struggles of students before the trauma is internalized and causes behavior that leads to unhealthy and dangerous life choices,” said Sonia Llamas, the district’s assistant superintendent of school performance and culture.

Depending on the issues, whether it’s household violence, lack of housing, fear of gangs or something else, students are linked up with specialists who provide counseling, guidance, case management and parent education programs. The district also deploys crisis response workers trained to help students cope with major traumatic events, among them losing a friend or relative to gang violence.

“Having this immediate, quick responsive support ultimately reduces most students’ need for long-term therapies in the future,” said Llamas.

The approach builds on a body of research that includes a landmark examination of long-term effects of traumatic events in children’s lives conducted by the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and Kaiser Permanente. The survey of 17,000 patients found early exposure to abuse, neglect, domestic violence and drug abuse contributes to chronic mental and physical health problems. Follow-up research has shown that experiencing violence at a young age can inhibit brain development, the ability to focus in school and a wide range of psychological problems.

“It’s this chronic, pervasive toxic stress that kids can’t really escape,” said Melissa T. Merrick, a behavioral scientist at the CDC’s National Center for Injury Prevention and Control.

Some of the issues Santa Ana officials are once again seeking to address played out in Angel’s life and continue to haunt his survivors, who grieve over his death and fear at least a few other family members could follow his path, according to interviews with relatives.

In 2006 a shrine in the living room of Hugo Secundino pays tribute to his slain son Angel, pictured at top. (Eugene Garcia, Register File)

But the Secundinos’ saga, as told by family members, public records and police, also illustrates the complex challenges officials can confront as they seek to heal children and families damaged by violence, and break resilient, multi-generational cycles of gang recruitment.

“These are families that come from poverty and have marginalized neighborhoods,” said Jorja Leap, an anthropologist at UCLA who studies gang culture and high-risk youth. “This is what children grow up with. It’s all of this in a kind of petri dish that leads to the cross-generational transition.”

One key is to change the expectations at-risk children have for themselves and their futures, said Aquil Basheer, who runs the Los Angeles-based Professional Community Intervention Training Institute, which works with communities worldwide to reduce gang violence.

“The first thing you gotta do is disrupt the normality of the gang members that are coming out of a multigenerational environment,” he said. “Their whole life is predicated on what they see coming from the family, coming from the smaller community circle, that most of them operate in.”

‘He threw away his cowboy boots’

Hugo Secundino was 17, living with his family in south Orange County and had dropped out of high school to go to work when Angel was born. He recalls being excited and running down the hospital hallway shouting.

His father, Inocente, now 68, said he came to the U.S. in the 1980s – a period of a large surge of immigration. “I came here looking for a better future for my family,” he said in Spanish.

He worked in restaurants as a dishwasher and cook and sent money back to his family in Guerrero, Mexico. His children, including Hugo, younger brother Inocente Jr. and other siblings, along with his wife, Dolores, migrated here within a few years.

Inocente Secundino moved up to a construction job and his wife worked in hotel housekeeping in Laguna Beach. In 1998, they bought a house in Santa Ana, fulfilling a dream. The home, about a mile from the civic center, still serves as a hub for the extended family.

Hugo and his young brothers were close and enjoyed “jaripeos” or bull-riding events. They wore rodeo attire and went to the events many weekends. But when Inocente Jr. was about 12, relatives noticed worrisome changes.

“He threw away his cowboy boots and didn’t want to go anymore,” Hugo Secundino recalled. Dolores Secundino said she was working long hours and sometimes double shifts, keeping her away from her children. “I regret not paying more attention to my son,” she said. “I should have spent more time with my children.”

After Inocente Jr. began attending Century High School in Santa Ana, he started skipping class, stayed out late, shaved his head and dressed in baggy clothes. His parents said they tried to impose discipline, kicking unwelcome acquaintances out of the house. His mother threw away the baggy clothes he borrowed from friends. She said she quit her job to stay home and provide more supervision of her son.

But it proved too little, too late.

One mid-summer day in 2006, Dolores was sitting on her porch when Inocente Jr., then 22, rushed home and entered the house. He emerged with a handgun and began riding away on his bicycle. She recalled chasing him, grabbing his shirt, trying helplessly to stop him.

He ignored her pleas. About a block away, he fired, hitting a 19-year-old in the back of the head, authorities said. He fled to Mexico, according to police, and was named the most-wanted gang homicide suspect by the Santa Ana Police Department.

He was apprehended at a relative’s home in Oregon two years later by a local and federal law enforcement task force, as he ate breakfast with his partner and two young sons, according to authorities and relatives. Inocente Jr. pleaded not guilty, but was convicted of first-degree murder and sentenced to life in state prison without the possibility of parole. He declined a request for an interview, according to a prison official.

Idolized his uncle

Inocente Jr. was the first in the family to fall into gang life, relatives said, but not the last.

When Angel was a boy, he and his parents lived for a time with his grandparents, Inocente Jr. and other relatives in the family’s three-bedroom Santa Ana home.

In 1999, during an argument, Hugo Secundino said, he slapped Angel’s mother across the face and was arrested. She obtained a restraining order, he said, and he was ordered to attend an anger management course. The couple separated soon after, he said. Angel’s mother could not be reached for comment.

Secundino said he lost touch with then 7-year-old Angel and a younger daughter. Court records show he failed to make child support payments and by 2004 owed $12,000 in back payments. Money was taken out of his paycheck for a time, Secundino said, but when he lost that job and failed to get regular work he couldn’t keep up the payments.

Secundino said he didn’t communicate with his children because he didn’t want “more issues with their mother.” Sometimes, he watched them from a distance, as they got on and off the school bus, he said.

When Angel was 13 years old, he rebelled and had a falling out with his mother, Secundino said. His son moved back with family in Santa Ana, splitting his time between the home his father shared with a new partner and his grandparents’ house across the street.

Angel came to idolize his uncle, Inocente Jr., who lived there, according to Hugo Secundino.

“My brother started pulling my son to hang out with his friends,” he said. “I would tell my brother that if he saw my son hanging out with gang members to send him home. But instead of keeping him safe, he ruined his life.”

Hugo Secundino still struggles with the pain of losing his 14-year-old son, Angel, to gang violence in 2006. He recognizes mistakes he made with Angel and now wants to be a better, more attentive parent to his children, he says. A bull rider himself, he watches bull riding videos with his 7-year-old son on Saturday, July 29, 2017.

Angel was vulnerable, hurt and suffered from lack of attention from his father, Hugo Secundino acknowledged. He said he was trying to re-establish a bond with his son in the months preceding his death.

In that period, Secundino said police officers picked up Angel several times, including for tagging a nearby school and trying to steal a car. Each time, they brought him to his grandparents’ home, Secundino said.

“I spanked him when police officers found him tagging and brought him home,” he said. “I told him I didn’t want him to hang out in the streets.”

Police saw the situation differently. Matt McLeod, the Santa Ana homicide detective who would investigate Angel’s killing, said the grandparents appeared “in the dark” about what was happening at their home. But he said suspected gang members would hang out in a rear patio and the Secundino family was viewed by police as “one of your true, if you will, generational families.”

“We had been there I don’t know how many times,” he said. Some of the adults they encountered, including Hugo Secundino, didn’t appear to be providing proper supervision of children and teens, McLeod added.

Angel continued to rebel and draw closer to his uncle’s gang, relatives and police said. He was skipping school and got a gang tattoo on his stomach. Someone tried to kill him in October 2006 as he walked with a friend down a Santa Ana street. A bullet struck the bottom of his foot. He escaped, but refused to cooperate with detectives in their investigation, police said. Secundino said he couldn’t get his son to assist detectives.

‘An execution’

Several weeks later, Angel spent the morning helping his dad renovate a studio apartment in the back of his grandparents’ home. Relatives said Angel hoped to move into the apartment with his teenage girlfriend, whose family also lived on the block.

Later, Angel told his family he was going with friends to buy new shoes for Christmas. A short time later, a friend of Angel’s arrived crying. Angel and others had been attacked, she told family members.

Secundino recalled he’d already been fearful because he heard a helicopter hovering overhead. He ran to the shooting scene but was kept back behind yellow police tape.

A group of gang members, most of them minors, had been riding around “hunting for enemies,” authorities said. Angel was ordered to get on his knees and shot in the head, according to police and court records. A 15-year-old also was fatally shot. A third teen was wounded in the stomach and left in a coma. He underwent several surgeries but survived.

The brazenness of the bloodshed was shocking, even to seasoned homicide detectives. “This was an execution,” McLeod said. “Get down on your knees, put your hands behind your back and the taking of lives. Very rarely do you ever see that, even in our world.”

Angel died unaware that he was going to be a father, according to relatives.

The violence didn’t end. During a wake held for Angel at his grandparents’ home, someone shot at the house, Hugo Secundino said. Five years later, when Hugo Secundino visited Angel’s grave, he discovered his son’s granite headstone had been broken into pieces.

Dolores Secundino, now 66, said the weight of knowing her grandson is buried at the cemetery and her youngest son is sentenced to life in prison takes a daily toll. Another son also is serving time in prison, she said.

She has trouble sleeping, gets constant headaches and has panic attacks. She suffered a stroke five years ago, which she partially attributes to stress, that paralyzed her left arm.

“I don’t know what I’m going to do with so many problems,” she said. “I think I’m going crazy.”

Hugo Secundino said after Angel’s death he once put a gun to his head and contemplated suicide. It’s difficult to visit his son’s grave because he still hasn’t fully accepted he is gone, he said.

“I was mad and angry at God because he gave me happiness when my son was born and then he took it away,” he said. “It was something that I never imagined would happen in my life.”

For years after Angel’s death, Secundino said he soothed bouts of depression and thoughts of suicide with alcohol and, at times, crystal meth and pot. Now, after therapy sessions offered through a local nonprofit, he said he’s found new strength and is trying to ensure his other children stay away from the streets.

A number of family members have moved out of Santa Ana and have steady jobs and stable homes, relatives noted. But Hugo Secundino and other family members say they worry about some members of the next generation, which includes more than 30 grandchildren of Inocente and Dolores Secundino. At least two of Angel’s cousins had associated with Inocente Jr. and Angel’s gang, and a third, who lived at the family home until recently, moved away, saying he feared for his life, relatives said.

Safe Haven

Gang detectives search a neighborhood where a suspected gang member fled when police turned down the street. Santa Ana’s Acting Chief David Valentin in mid-July began shifting officers and resources into a seven-day a week patrol to reduce street violence.

Martinez, the mayor pro tem, said her experience shows intervention and exposure to positive role models creates hope and can make a difference in the paths children take. Her family moved repeatedly from house to house. One of the longest stays is etched in her memory as a chaotic mix of drug dealing, gang presence and police raids – “all kinds of madness,” she said.

A passion for basketball, the “safe haven” of the local Boys & Girls Club, psychological counseling at school and a good social worker helped her avoid the trips to jail and prison that several siblings and cousins took, she said. She was the first in her family to graduate from high school and earn a college degree.

“I’m proof that it doesn’t matter where you come from,” she said.

Angel’s daughter dreams of being a scientist or a nurse. She says she likes basketball and concedes she finds some subjects challenging. She has strong bonds with her father’s family, but lives elsewhere in Orange County with her mother, who declined to be quoted for this story.

The girl has been trying to understand her father, what happened to him and why he is gone, relatives said. She learned of her father’s murder two years ago. “My grandma told me that somebody shot him,” she said.

She has many questions. But she said some relatives, including her mother, don’t want to dwell on the past.

“My mom told me that he was a good guy,” she said at the cemetery, her eyes moistening as she rested on a bench near the grave. Relatives recall she would dance and laugh there as a toddler, not realizing the meaning of the place.

“I had never heard (her) cry for her dad,” Hugo Secundino said later.

Secundino has three young boys, ages 10, 7, and 3, with his partner Sayuri Estrada. He said he now recognizes mistakes he made with Angel and wants to be a better, more attentive parent and provide a more stable home to his children.

The couple enrolled their two older sons in an after-school program to help them academically but also to keep them away from street life. Estrada said she has given up her job cleaning houses to dedicate more time to her children.

Several months ago, Secundino and Estrada moved their family away from the neighborhood where Angel was killed, to another part of Santa Ana.

They hope their efforts will give the boys a better chance for a life apart from the dangers of gangs. They say they are very sensitive to signs of rebellion, particularly in their oldest son.

“He wants to hang out with his friends,” Secundino said. “But I don’t like it.”

[This story was originally published by The Orange County Register.]

[Photos by Mindy Schauer, Orange County Register/SCNG.]