Lehigh’s growth exposes a hard reality about South Bethlehem’s real estate market

This article was produced as part of a project for the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism’s 2021 National Fellowship.

Other stories by Sara Satullo include:

Are you a renter in Southside Bethlehem? We want to hear from you.

2 new projects slated to bring 95 new apartments to Bethlehem’s 4th St.

The fight for the heart of a South Bethlehem community

Will we recognize South Bethlehem after a real estate boom and pandemic? Introducing Edged Out.

Deal gives displaced South Bethlehem residents, businesses more time

South Bethlehem is a collage of cultures. Residents wonder if that can continue.

The fallout when you’re Edged Out

Bethlehem Southsiders show ‘striking’ love of community, optimism about future, forum report says

Weary of living among student housing rentals, Murdocc and Karen Saunders sold their Hillside Avenue home in South Bethlehem in late 2020. Three generations of Karen Saunders' family lived in the home. They've yet to find a new home and regret the sale.

Saed Hindash | Para lehighvalleylive.com

To read this story in Spanish, click here.

Three generations of Karen Saunders’ family have called Hillside Avenue in South Bethlehem home.

A job at Bethlehem Steel brought her Slovakian grandfather to the gritty, industrial hub of the Steel giant. He built his house on the avenue perched on the side of South Mountain, which is locally known as Slovak Hill, an ethnic enclave where immigrants built their homes by hand.

The house at 727 Hillside passed from her grandfather to her father and then to Karen Saunders and her Grenadian husband, Murdocc.

“Our goal was to make this house beautiful again, make it the pride and joy of the Southside,” Murdocc J. Saunders recalled. “And we hoped that would spur our neighbors on to do the same thing.”

For a while, the plan was working. They welcomed two sons, now 7 and 11, and nurtured a sense of community on Hillside Avenue.

Instead, Lehigh University came to Hillside Avenue. A neighbor sold to a student-housing developer in 2018, setting off a chain reaction that led the Saunders family, feeling beleaguered and wistful, to sell their beloved home in September 2020.

“We were surrounded by college students. There was no parking. We saw some (sexual) acts I didn’t want my children to see. Things they should not be seeing on public streets,” Murdocc Saunders said of their decision to sell. “It broke my heart. It felt like I was taking a piece of her family tree away.”

Unable to secure a house in the Lehigh Valley’s uber-competitive market, the Saunderses find themselves two years later still renting a two-bedroom apartment in Allentown they thought was temporary. And Bethlehem’s lost a multi-racial family committed to improving their neighborhood.

Lehigh University, elite and eager to grow, sits in the middle of the diverse working-class community of South Bethlehem. Its ambitious presence has fueled an investor-driven student housing boom that’s reshaping the community. And it coincides with Lehigh’s recent efforts to grow its student body and rental portfolio, reigniting old fears for residents who recall how the university and city once used urban renewal to level a Southside community.

Lehigh, which regularly is cited by Princeton Review as a top party school with some of the worst town-gown relations of any campus, now tries much harder to be a good neighbor. But its efforts still fall short in the eyes of some city officials, advocates and Southside residents.

It’s a complex tale that shows how the dreams of an elite institution can sow anxiety and difficult decisions all across the proud, working-class community with which it shares a mountainside.

At the heart of the conflict are the hard realities of a local real estate market, inflamed by the pandemic, that lacks options both for lower-income renters and middle-income buyers. The low cost of housing on Southside attracts investors who see student housing as a great bet. Toss into that situation a bunch of well-off (if not always well-behaved) college students, whose parents stand ready either to pay high rents or buy up available stock.

“The economics (for developers) seem so straightforward: buy working-class houses cheap and rent at top dollar to wealthy students,” said Seth Moglen, Saunders’ neighbor on Hillside Avenue and a Lehigh professor. “It is like a printing press.”

But what’s good business for developers creates a situation that drives up rents for everyone.

“And that does displace residents,” said Jill Seitz, senior community planner for the Lehigh Valley Planning Commission.

Lehigh officials say this syndrome is not something they intended or want to continue.

“There’s no hidden agenda that area residents should be worried about. We really do want to be good neighbors, good community members,” said Erin Kintzer, Lehigh University’s director of real estate services. “The faculty and staff housing is to really meet those needs. It is not to take over a neighborhood.”

El campus principal de Asa Packer de Lehigh University se encuentra en el centro de South Bethlehem, un vecindario de clase trabajadora con una vibrante historia industrial. El crecimiento de Lehigh a menudo lo pone en desacuerdo con sus residentes. Saed Hindash | Para lehighvalleylive.com

But in a neighborhood where people still recall the Lost Neighborhood, blocks of working-class housing that Lehigh tore down in the 1960s then left as parking lots for years, many are not convinced by such vows from Lehigh.

The numbers vividly tell the impact of the student housing boom.

By this fall, rents in the ZIP code that covers South Bethlehem rose by 34% since early 2019, according to Zillow. The typical apartment is going for $1,600 a month, nearly double the mortgage for a typical single-family home in the neighborhood.

This has pushed some lower-income families into the bounds of nearby school systems that lack the robust network of social supports the Bethlehem Area School District (sometimes aided by Lehigh) offers. The resulting displacement has been so significant that the school district recently brought in a housing counselor to help families.

“The affordability gap is the biggest barrier for us to get over,” said Alicia Creazzo, the Lehigh-funded community school coordinator at Broughal Middle School, a school of about 500 Southside students. “For the majority of our families in South Bethlehem it is still a struggle.”

Bethlehem’s new mayor, J. William Reynolds, is also concerned.

“If somebody can get $3,500 to $4,000 a month in rent from students, that is financially much more enticing than renting to a family,” said Mayor J. William Reynolds. “... I think what we’ve seen in our more residential neighborhoods is the influence of Lehigh University and that profit motive.”

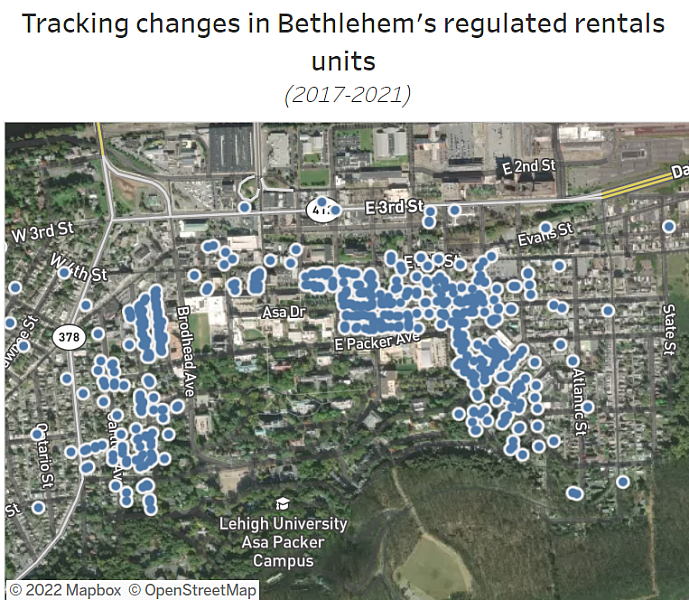

The student housing pressure in the neighborhood intensified to the point that in 2021 the city acted to restrict student housing to certain blocks around the university, ceding what was already lost in hopes of preserving what remains.

The Saunders saw themselves as the future of South Bethlehem. A multi-racial family descended from the immigrants who first built the community, they shopped and bought local. They cherished their neighborhood for its economic and racial diversity.

For Murdocc Saunders, and many who came before him, owning a tidy house carved in South Mountain was a path to building intergenerational wealth, to “get out of living paycheck to paycheck and get into the middle class.” Now, he’s back to renting, and students fill the blocks where he once wove his dreams.

“If my house came back for sale I would buy it back today. I do regret my decision,” Saunders said. “That house is part of me.”

Este mapa de Bethlehem de 1872, muestra los primeros días del municipio de South Bethlehem. El municipio y Lehigh University, que se muestra en la esquina derecha, fueron ambos fundados en 1865. Bethlehem sur, norte y oeste se fusionaron para formar la moderna ciudad en 1917. Colección de la Biblioteca Pública del Área de Bethlehem

A Southside anchor

Lehigh’s founder Asa Packer was an industrial pioneer, building the Lehigh Valley Railroad and a coal mining company. In 1865, wanting to give back to the region that made him a tycoon, Packer donated 57 acres and $500,000 to establish the tuition-free Lehigh University. He believed an educated workforce was crucial to a thriving economy.

Now 157 years later, Lehigh employs more than 2,000 people and enrolls about 7,000 undergrad and graduate students, who pay $72,300 to attend. The student body is 61% white and the median family income is $167,600.

“I remember reading Lehigh University was created for people in the Southside to have an education,” said Lidia Gonzalez, 39, an immigrant homeowner, small business owner and single mother. “I don’t think there are a lot of us going to Lehigh.”

The university’s campus covers 2,107 acres — all but 500-some are within the city — with its core Asa Packer campus nestled on South Mountain in the heart of a residential neighborhood, steps from the downtown. The urban campus is largely built-out, leaving many in the community curious about how the university plans to grow.

In 2016, Lehigh announced an ambitious growth campaign dubbed the Path to Prominence. The university plans to add 100 faculty and up to 1,800 undergraduate and graduate students in the coming years. The news spurred a rush of new student housing in existing neighborhoods, with additional housing proposed downtown.

“We have not asked any developer to build any additional housing because we don’t need it,” said Adrienne McNeil, Lehigh’s assistant vice president for community and public affairs. “When we announced the expansion plan, we announced the additional residence halls, which are now complete. We kept to our promise: we are not putting more students in the neighborhood.”

El nuevo edificio del College of Business se levanta al otro lado de la calle de una propiedad de alquiler a estudiantes de Fifth Street Properties en Van Buren Street. Saed Hindash | Para lehighvalleylive.com

Lehigh intends for most of those students to be housed on campus, said its new president Joseph Helble. Currently, 72% of undergrads live on campus, the highest figure in more than a decade.

“The challenge is to find ways for students and faculty and staff to integrate into and be a part of the neighborhood and the community without becoming the neighborhood and the community,” Helble said. “If it were monolithic then it would just be an extension of the university and we don’t want that.”

The university reports the number of students living off-campus has held steady at about 1,500 for the last five years, except for a pandemic-related rise last year when only freshmen could live on campus.

The growth in Southside student housing is most clearly seen in the city’s own data tracking regulated rental units — places where three to five unrelated people live. There were 33 licenses in 2010 when the city was not strictly enforcing annual registration. Today, there are 676 with 87% issued in the last six years. Only 11 new licenses were issued in 2021 compared to 75 the year before and 187 in 2019.

(Not all students moving into the Southside attend Lehigh — some are from nearby Moravian University, DeSales University, Penn State Lehigh Valley and Northampton Community College. Moravian in 2010 restricted off-campus living to only 50 seniors a year.)

Moglen, the Lehigh professor who lives on Hillside Avenue, the same street the Saunders fled, says he has five DeSales fraternity brothers living next door, with more DeSales students around the corner.

“College students are wonderful,” Moglen said. “But universities and colleges should not offload onto adjacent neighborhoods their most challenging campus social problems.”

Some Southside homeowners say students can make them feel unwelcome in their own homes. They contend with late-night parties, students peeing in their yards, drinking, littering and double parking.

“We never got that reciprocal respect,” Saunders, Moglen’s former neighbor, recalled. “They felt temporary. They knew they were only there for a defined period of time. They really didn’t take pride in the neighborhood like we did.”

Lifelong Southsider Diana Powell said living among Lehigh students on Hillside Avenue was hell.

“You have drunk females shouting out the window disgusting filthy things about wanting to satisfy their libido very plainly at 1 o’clock in the morning,” Powell, who grew up on Carlton Avenue, another street invaded by student rentals. “... And after the bars close male students watering your trees.”

City Councilwoman Rachel Leon said she is infuriated by the trash Lehigh students leave in their wake when they move out each spring. Broughal students must wade through sofas, broken televisions and piles of garbage on their way to school, she said.

“What does that say to a child when they have to walk through a trash pit to get to their house?” Leon asked. “That is infuriating to me that an institution of hyper-intellectual people can’t get that if you dump trash in front of a kid’s house that is he is going to internalize that.”

To combat this Lehigh organizes the Great Southside Sale, a massive yard sale that raises more than $20,000 for Southside children.

El socio gerente de Fifth Street Properties, Louis Intile, se para frente a sus casas de East Fifth Street. Fifth Street compró a la ciudad la propiedad arruinada y la derribó para construir las viviendas de alquileres estudiantiles. Saed Hindash | Para lehighvalleylive.com

A solid investment

Louis Intile gets a tad weary of the proclamations of doom about student housing on the Southside. He’d rather focus on improving the safety of existing rentals and job prospects for residents.

Intile is a managing partner of Fifth Street Capital Partners, one of the city’s larger locally-owned student housing companies. His company’s earned a reputation for high-caliber renovations of aging housing stock and rebuilds of those that are too far gone. About 98% of his renters attend Lehigh and he thinks college students often unfairly get a bad rap.

Student housing isn’t proliferating in his view. The city is just doing a better job of tracking it.

Intile thinks Bethlehem should embrace the way students with lots of disposable income help the local economy. Another plus he cites: Companies such as his pay taxes into the school district without sending children into the system.

“Not every time a house changes over it is a bad thing for the neighborhood,” Intile, who is very involved in Southside organizations, said.

Across the country, student housing real estate investment trusts are a growing market, said Tim Tepes, president of the Greater Lehigh Valley Realtors and co-owner of Assist 2 Sell Buyers & Sellers. Bethlehem started seeing corporations buy up student housing after the city and Lehigh University cracked down on absentee landlords, who then started selling off their holdings, he said.

“It was an unintended consequence of making (student housing) safer,” Tepes said.

Amicus Properties es un recién llegado al mercado de viviendas estudiantiles de Bethlehem, pero rápidamente han adquirido una gran cartera, fácilmente identificable por las banderas estadounidenses. La compañía está abriendo una oficina en Fourth Street. Saed Hindash | Para lehighvalleylive.com

Other major players in the student housing market locally include Amicus Properties, an out-of-state firm whose 75 properties are identified by their bright yellow doors and crisp American flags, and Campus Hill Apartments, which has changed ownership several times in recent years. Amicus, which is opening an office on Fourth Street, did not respond to requests for comment.

Lehigh’s Kintzer said companies like Amicus are attracted to Lehigh because the cost of real estate near its campus is much lower than in the big cities where they got their start.

“They can get a lot more bang for their buck in South Bethlehem and the returns are probably better,” she said. “We are going to be affected by what is happening in all of those other markets.”

Intile, of Fifth Street Capital Partners, just doesn’t buy the argument that developers like him are driving an affordable housing crisis in south Bethlehem, which he contends is still quite affordable.

“You’re telling me that a $150,000 home is not affordable when the national average is $360,000. It’s a function of 2% interest rates, it’s a function of not enough supply,” Intile said. “But it’s not a crisis and it’s not caused by student housing. It drives me wild because it has nothing to do with student housing actually.”

The mayor, community leaders and many residents disagree. And they worry once an $80,000 home becomes a student rental, it will never sell for that low again.

“I do think that the city has to be aggressive moving forward as far as stopping that expansion,” Reynolds said. “That is unquestionably one of the things that has led to the increase in prices in some of our South Bethlehem neighborhoods.”

Mirando hacia el oeste en East 5th Street, una calle de South Bethlehem que es principalmente viviendas para estudiantes. En la parte trasera derecha se encuentra el nuevo edificio de Health, Science and Technology de $ 145 millones de Lehigh, el edificio académico más grande en el campus de Asa Packer y hogar del nuevo College of Health de la universidad. Saed Hindash | Para lehighvalleylive.com

The city implemented the student housing zone in concert with residents like Saunders and Moglen. Existing student rentals outside of the zone are grandfathered in and must register annually; any new ones require zoning board approval.

“We had zero control on location and spread of student housing leading up to the zoning and ordinance change,” said Alicia Miller Karner, who was director of community and economic development under the last mayor when the zone was enacted.

The city was acutely aware that, in setting, the boundaries for the student overlay district, it was picking winners and losers. A home just outside the zone could be worth $50,000 less than the same house within it.

“People seemed to be OK with it,” said Anna Smith, a resident and community organizer involved in the process. “They wanted a neighborhood.”

One group of buyers has not had problems with the affordability of Southside properties lately — the parents of Lehigh students.

Desperate for a place for their kids to live after the school announced only freshmen could live on campus for the 2020-21 school year, they got in on the local housing market. Parents and Realtors went door to door looking for anyone willing to sell.

Murdocc y Karen Saunders se ubican afuera de su anterior casa en Hillside Avenue, que lamentan haber vendido. Vivir entre viviendas de alquiler para estudiantes se hizo insostenible para la familia a fines de 2020. Saed Hindash | Para lehighvalleylive.com

The Saunders family first resisted. But they were ready to go once their son saw students engaged in sexual activity on the street.

“We didn’t want to raise our boys like that,” Murdocc Saunders said.

A Realtor showed up on the Saunderses doorstep with a copy of a Lehigh family’s investment portfolio shortly after they listed the home in August of 2020. The parents who bought from the Saunderses “didn’t see the house,” recalled Murdocc Saunders. “They sent a Realtor on a Sunday morning and asked us to take the house off the market and pay us cash.”

Even with their money in hand, the Saunderses can’t find a house to buy in the Lehigh Valley’s tight real estate market, where many buyers are losing out to all-cash offers in bidding wars.

It speaks to a chasm of wealth between the newcomers Lehigh is bringing to the Southside market and the long-time residents.

The median family income for Lehigh University students is $167,000 and 67% come from the top 20%. The Southside reports a median household income of around $40,000 and a poverty rate of nearly 28%. The racial divide between renters and homeowners in the city of Bethlehem is just as wide. Only 30% of Latinos and 23% of Black residents own homes compared to 63% of whites, according to the U.S. Census.

“Why do we want rich college students to get a property that a low-income family needs?” asked Alan Jennings, the recently retired executive director of Community Action of the Lehigh Valley.

Lehigh University's Asa Packer campus has seen a boom of new academic buildings and residence halls in recent years. The new College of Business building, 459-461 Webster St., is shown rising in the fall of 2021. Saed Hindash | For lehighvalleylive.com

Where Lehigh goes next

Lehigh officials maintain the university will look to its Mountain Top or other campuses for future growth, not residential areas of the Southside.

Still, the way the university keeps building and buying properties in the neighborhood — more than 30 in the last six years — creates anxiety. The majority are being used as student and faculty rentals, although some deteriorated properties have been torn down for parking.

“The university can think about things in really long horizons,” Lehigh’s Kintzer said.

After 150 years of existence, Lehigh buys property for both immediate needs and because it thinks a property could be an asset in half a century, she said.

Lehigh hired Kintzer six years ago to head its fledgling real estate office, tasking her with managing its substantial land holdings and building a residential rental program.

Many university faculty and staff seek traditional housing close to campus, she said, adding that Lehigh’s rental holdings look meager compared to its peers, including arch-rival Lafayette College in Easton. That’s why she’s working to bolster the supply of university-owned housing for faculty and staff.

“We felt that was a good way to meet the needs of faculty and staff,” Kintzer said. “We can have the right kind of controls of houses immediately adjacent to the campus. We can ensure they are well maintained and look good at the entrance of our campus for visitors.”

Durante las vacaciones de Navidad, Lehigh University demolió una casa en 205 y 214-16 Summit St., en un acceso clave del campus. La casa en 205 Summit St. se encontraba inhabitable. Según una portavoz, la universidad aún no tiene planes para la propiedad. Matt Smith | colaborador ehighvalleylive.com

Kintzer as a rule primarily buys from investors, not homeowners. Many of the properties Lehigh has bought sit on the western edges of Lehigh’s campus, near Broughal Middle School.

Kintzer hopes the folks in university housing can live in harmony with long-time residents.

“I never want them to feel any pressure to leave,” Kintzer said. “We want them to feel the opposite and feel welcome to stay and never feel it is 100% just students in a neighborhood.”

The university’s leadership says it takes its role as a community anchor institution seriously, investing in the local schools, arts district and streetscape improvements.

But many families are feeling the pressures to leave as the conversion of so many homes into student rentals leaves fewer options for local residents to rent and buy. Renters face fierce competition and rising rent prices for units that are often substandard. Many report settling for low-quality housing in less than ideal locations just to stay in the Southside.

And not all homeowners in South Bethlehem look at their rising property values as a good thing if it means their neighbors get pushed out. Historically, the Southside’s been a place where anyone could get their start, said Delia Marrero, a resident whose grandparents helped found the city’s Puerto Rican Beneficial Society.

“We don’t have the equity, credit or generational wealth,” Marrero said of many Southsiders. “We are catching up constantly. When the place where you can catch up no longer exists: what happens? It becomes less accessible to people who have already started behind the line.”

Some would like the school to take ownership of the problems spilling over into residential areas with a stronger focus on neighborhood stabilization, doing things like a more robust housing program aimed at converting rentals back into owner-occupied homes.

Algunos residentes de South Bethlehem desean que la Lehigh University dirija sus esfuerzos de construcción más hacia la comunidad. Saed Hindash | Para lehighvalleylive.com

Lehigh envisions this as an approach with four integral pillars: improving public education in South Bethlehem; stabilizing the neighborhood; fostering economic vitality; and public safety, including a strong town-and-gown relationship.

Currently, Lehigh pays for three community school coordinators in neighboring Bethlehem school district schools and Lehigh students volunteer in the local schools. University police share a downtown substation with city police and it offers a meal plan that can be used in downtown businesses. The school hosts many events for Southside families, like the Halloween Spooktacular and Living La Vida Lehigh, when elementary students get to spend a day on campus. It’s moved staff into the downtown and invested in streetscape improvements on South New Street.

“We do feel we have a responsibility,” McNeil said. “We are not successful if the Southside is not successful.”

The Lost Neighborhood

Yet for many Southside residents, an invisible wall persists around the campus. They feel unwelcome on the campus. And the distrust they feel dates back nearly more than a half-century — and the history of “the lost neighborhood.”

“For many of our families (the Lost Neighborhood) feels like yesterday,” said Carolina Hernandez, director of Lehigh’s Community Service Office and associate director of the Center for Community Engagement. “It takes years for us to build trust and just seconds to break it.”

Over Christmas Break, Lehigh University demolished a home at 205 and 214-16 Summit St., a key campus gateway to its campus. One home was not habitable and the other converted to a business. Lehigh has no immediate plans for either property. Matt Smith | lehighvalleylive.com contributor

In the 1960s, to support the growth ambitions of Lehigh and Bethlehem Steel, two Southside neighborhoods were leveled, displacing more than 1,200 people. Northampton Heights, where many people of color who worked for Steel lived in a community, was erased, to make way for a new basic oxygen furnace.

Lehigh, meanwhile, used straw buyers to quietly purchase homes in a four block radius north of West Packer Avenue. The university neglected the properties enough the city blighted them, paving the way for the 1966 bulldozing of an entire neighborhood. Much of the site sat fallow, as parking lots, for years.

“It wasn’t lost. It was stolen from them,” exclaimed Powell, the lifelong Southside resident who recalls swimming at the pool of a demolished synagogue. “The city used eminent domain to take it.”

Greg Farrington, Lehigh’s 12th president, arrived in South Bethlehem in 1998, coming from the University of Pennsylvania, often considered a model for higher-ed-driven neighborhood revitalization.

On his first visit to Bethlehem, he recalls, he stood in that desolate parking lot, looking at a bulletin board covered in old notices and a telephone booth with the receiver dangling in the air.

“It was pretty lonely,” Farrington, who left in 2006, recalled. “I thought there was a very powerful message there. It appeared to say to a casual visitor: the campus is here and it is up the Mountaintop and the community is here. This parking lot was like a moat.”

Farrington’s first proposal was replacing the parking lot with a new campus square facing the community, along with 250 student residences, a parking garage and small shopping area aimed at blurring the border.

Farrington Square se encuentra en un terreno que una vez abarcó un vecindario de South Bethlehem. Hoy en día, alberga un mercado semanal de agricultores y restaurantes locales. Cuando el ex presidente de Lehigh, Greg Farrington, visitó por primera vez la universidad, era un estacionamiento desolado que comparó con un foso entre la universidad y la comunidad. Saed Hindash | Para lehighvalleylive.com

Today, the site hosts a public farmers’ market five months a year and is home to outposts of Johnny’s Bagels, the Bethlehem Dairy Store and the campus post office and bookstore. It’s called Farrington Square.

“It was about turning Lehigh from just looking up the mountaintop to turning Lehigh to face the community,” Farrington recalled. ”As much as possible, you want to have the community around the university develop into a real community of families, of real people, not just a rental community of students nine months of the year.”

Lehigh’s made progress at opening its campus, but the wounds in the community are deeply ingrained, Leon, the city councilwoman and resident, said.

“Those divides go back to historically the way Lehigh has talked about the Southside in public and in private in meetings with students,” Leon said. “How they painted Southside as this dangerous place to live, as if we were having a murder every five feet. Those are the things that get under the skin.”

Can Lehigh do more?

While many Southside residents are far from thrilled by the large, multi-use developments happening in the neighborhood’s business district along Third and Fourth streets, developers and Lehigh’s leaders suggest the housing units in those projects could be part of the salvation of residential neighborhoods farther up the hillside.

“Students are shifting from different living situations. When a student moves into an apartment on Third and Fourth Street, those students are vacating a row house on Hillside,” Kintzer said. “There is a shifting of things that happens that ultimately frees up properties that might be better aligned for those who are looking. That process takes time.”

Currently, developers are planning about 228 new student housing units in the downtown. With more housing options, Lehigh students are wielding more power in the rental market — they no longer sign leases two years in advance — and more landlords are upgrading properties like Fifth Street.

El socio gerente de Fifth Street Properties, Louis Intile, muestra sus viviendas de alquileres estudiantiles en South Bethlehem. Saed Hindash | Para lehighvalleylive.com

Jennings, the former nonprofit leader, says Lehigh remains the 800-pound gorilla in this particular real estate market. He said it should undertake a comprehensive, research-based and market sensitive approach. The university should deliberately bring more students back on campus and try to recapture investor-owned properties, he said.

“I think it should be identifying multi-unit houses in disrepair, get them out of the market, fix them up and put them on the market discounted to faculty,” Jennings said. “This should be a common tool.”

The University of Pennsylvania saw great success with a multi-pronged community revitalization effort. It offered forgivable cash loans for faculty and staff who bought homes in West Philly, mortgage guarantees and financing for closing costs and home improvements. Penn also rehabbed blighted properties and sold them to homeowners.

Currently, Lehigh offers faculty and staff an incentive to buy a home close to the university through a five-year forgivable loan of up to 10% of the purchase price for a maximum of $7,500, as well as a $2,500 curb appeal deferred payment loan for exterior projects. The program’s been tweaked and expanded since its 1999 creation with more than 30 people using the program.

Kintzer thinks a multi-pronged home-ownership subsidy program like those at Penn, Brown and Princeton is several years away. She’s not interested in bailing out investors.

“We’ve been at the table with Community Action, who is really studying this issue,” McNeil said, referencing Jennings’ former employer. “Certainly we think affordable housing is definitely important in any community.”

Many residents interviewed for this story want Lehigh University to consider affordable housing a key part of its responsibility to the community it calls home. That would go a long way to engender better town-gown relations.

Still, repairing the tensions that the Princeton Review rated so poorly seems destined to be a case of one step forward, one step back for a long time to come.

The new 10-foot Lehigh sign on its newest completed building has been polarizing. Kurt Bresswein | For lehighvalleylive.com

As for the Lost Neighborhood, the university just filled in the last vacant plot with its largest building ever — the $145 million Health, Science and Technology building, dubbed HST. It was designed to face the community as a campus gateway.

In early December, Lehigh for the first time lit the 10-foot LEHIGH sign atop the six-story HST. The university likened the glowing, sprawling letters to a beacon over South Bethlehem.

“The letters can be seen from vantage points across the city—a reminder of Lehigh’s connection to the community,” the university said announcing the illumination.

The response in a popular Facebook group for residents was considerably less enthusiastic.

“They own the Southside so they can do as they please,” one quipped.

City Council member Leon was even more unsparing.

“People who don’t live in Southside think it is so nice,” she said. “The people who live on Southside think, great, I just live on Lehigh’s campus now.”

Our journalism needs your support. Please subscribe today to lehighvalleylive.com.

Sara K. Satullo reported this story while participating in the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism’s 2021 National Fellowship, which provided training, mentoring, and funding to support this project. She may be reached at ssatullo@lehighvalleylive.com.

[This article was originally published by Lehigh Valley Live.]