Long hours, tough calls way of life for 2 rural Missouri EMS stations

The story was originally published by the Springfield News-Leader with support from our 2025 National Fellowship.

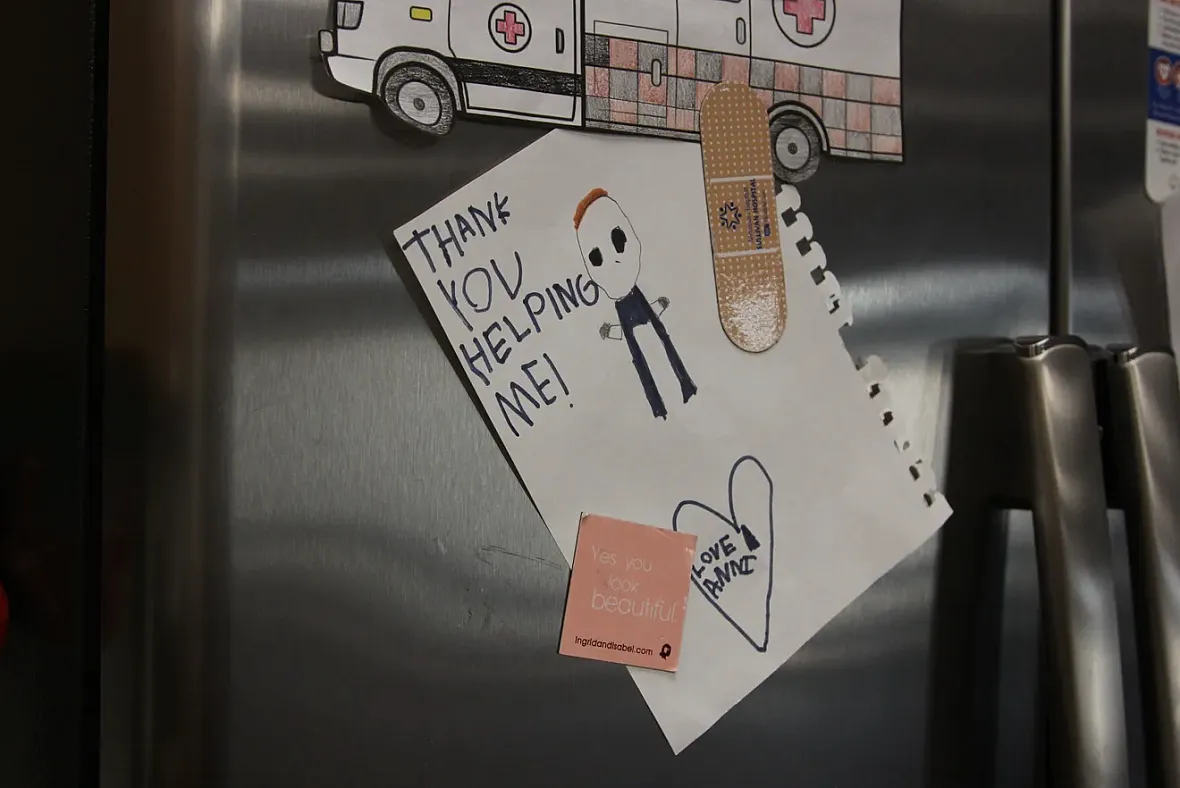

A thank you note from a patient hangs on a fridge at the Washington County Ambulance District Headquarters on Sept. 30, 2025.

Susan Szuch/Springfield News-Leader

It's the last day of an unseasonably warm September and MacKenzie Williams is near the end of her 12-hour shift at the Washington County Ambulance District Headquarters in Potosi, Missouri. She's currently studying to become a paramedic, and immediately after this shift ends, she'll start another 12-hour shift as an emergency medical technician.

After that, she'll go home to her 5-month-old son and 4-year-old daughter, trading places with her husband, who also works at the ambulance district.

At WCAD, those who respond to 911 calls work for 48 hours and then take 96 hours off. In between, there are folks like Williams who take 12-hour shifts as well. Because of their location in a rural area, the Washington County staff tend to work longer shifts than their counterparts in urban areas.

The night before was hectic, Williams said, with a call that required driving 70 miles to a St. Louis hospital and staying there until 2 a.m. This particular morning, and into the early afternoon, things have been almost unbearably quiet.

"It's because I'm a student. Then once I switch over (to my EMT shift), it's going to be run run run run run run," Williams said.

"It comes in waves for us, typically," said Cody Campbell, a registered nurse who runs calls with WCAD. "When it slows down like it has been over the last couple months, it’s just a matter of ..."

“When the shoe drops,” fellow EMT Tyler Weir said, finishing the sentence.

The district's B-shift has gathered in the station's living space, which is an open room with a kitchen, recliners in front of a TV, a patio and a small office with office chairs and desks. While waiting for 911 calls, they've been ribbing each other over food choices (a colleague's crunchy peanut butter gets graffitied), working on coloring pages to decompress ("Who colored the ambulance green?") and generally giving each other a hard time like any other close-knit group of colleagues.

When two calls come in at once that afternoon, everyone kicks into action. Williams goes on her only call as a student that day, transferring a patient from Washington County Memorial Hospital to an acute care facility.

Paramedics Devin Nahlik and Tony Mingo and paramedic student MacKenzie Williams prepare to transfer a patient from Washington County Memorial Hospital in Potosi on Sept. 30, 2025.

Susan Szuch/Springfield News-Leader

Rural areas are 'the Wild West of health care'

Potosi is a small town in Washington County about 70 miles southwest of St. Louis. At the 2020 Decennial Census, it was home to about 2,600 people, and is where the Washington County Ambulance District is headquartered.

While definitions vary depending on what government entity you're talking to, Washington County and the two other counties WCAD borders and serves — Reynolds and part of Dent County — are classified as "rural." In 2017, one in five Americans were classified as living in rural areas, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. (The Census Bureau defines a rural area as being sparsely populated, having low housing density and being far from urban centers.)

WCAD has four stations and five advanced life-support ambulances, in addition to a mobile integrated health team that is staffed by community paramedics.

EMS in rural areas have longer transport times, which means that personnel often must do more than just drive someone five minutes to the nearest hospital.

"It’s like the Wild West of health care is the only way to put it. What you do has to work now, it can’t wait until later," Campbell said. "If it doesn’t work now, it ain’t gonna work. You ain’t gonna get to a hospital.”

Tony Mingo, paramedic division chief of the mobile integrated health program at Washington County Ambulance District in Washington County, Missouri, makes sure the ambulance is ready to go on Sept. 30, 2025. Though Mingo is in charge of the MIH program, there are days he also runs 911 calls.

Susan Szuch/Springfield News-Leader

Mercy Emergency Medical Services Executive Director Bob Patterson, who oversees Mercy EMS stations across Missouri, said rural emergency medicine is a different beast entirely than what is experienced in metro areas. WCAD is not affiliated with Mercy, though it does transfer patients to and from Mercy hospitals.

"Typically, these guys are going to see it all, from A to Z: Shortness of breath, cardiac arrest, motor vehicle crashes. You name it, we’re going to see it. And that’s the heavy responsibility we put on these teams. They’ve got to treat everything from birth to death," Patterson said. "So they’ve got to have that knowledge to be able to take care of that whole spectrum. We’re like the emergency department in that regard; you have to be able to take care of everybody.”

Despite the vast array of conditions rural EMS staff see daily, there are common themes.

“It definitely has different seasons of what you see most," Williams said. "I think consistently we have a lot of mental health and substance abuse, is what we mainly see a lot of around here."

In rural areas, people are more likely to be older; have higher rates of chronic diseases like high cholesterol, high blood pressure and diabetes; and have less access to healthcare than their urban counterparts, according to the Rural Health Information Hub, leading to a sicker population.

Given the insurance and financial challenges also prevalent for folks in rural areas, EMS is often the safety net for some of these communities because they don’t have a primary care physician. However, when patients call EMS for basic medical care, already scarce resources get stretched thinner.

For another rural station across the state, it's hard to catch a breath

On a July morning more than 200 miles away from Potosi, Mercy paramedic Sam Evans was wrapping up a lively shift in Branson. When she and her partner rolled up to the Mercy Branson West station around 9 a.m., it followed a night of non-stop responses and a 4:30 a.m. wake-up call.

Finally, after 24 hours on shift, she had a chance to wash their ambulance.

“It’s supposed to happen every day, but I got up at 4:30 this morning (for a call) and then we just got done with another call (around 9 a.m.)," Evans said. "We just got back and ate breakfast on the way to the call, so I drank most of my coffee on the way there.”

It's busier in the summer, when people come out for water-related activities, but "this service is pretty steady here year-round," Patterson said. "Nobody's sitting today."

Evans has been with Mercy for most of her 10-year career but got her start in the Columbus, Georgia, area. Looking back, the day-to-day definitely differs, she said. Columbus, a more urban area, saw short transports with "25 calls in 24 hours," with EMS crews often waiting at the hospital for hours to unload a patient.

"Here, you have a long transport time in comparison to (Georgia), where you have a 5-minute transport and sometimes the hardest thing is getting the patient out of the house,” Evans said.

In rural areas, she said, the time isn't spent waiting to unload patients. If they’re really sick, and you’re far from a hospital, “you’re looking at an hour and 15 minutes, at least, with a patient." One thing is consistent, though: It can be hard to get patients out of their homes no matter whether they're in a rural or urban setting.

Mercy's Branson West emergency medical services station is at 59 Meadow Lark Road in Branson West. Branson West is part of Stone County, which recently voted to create an ambulance district. Mercy is the EMS provider for Stone County.

Susan Szuch/Springfield News-Leader

"Here, everything is rocky. These cots don’t roll over rocks very well," Evans said, adding that sometimes it comes down to not having enough people to maneuver things safely, especially in areas where there are only volunteer fire departments. "The cot weighs 200 pounds and getting that out of a house gets more difficult when you get somebody who weighs 250, 300, 400, 700 pounds — you need manpower and that’s not a super easy thing to come by. You gotta wait (for help to arrive)."

One of the calls that morning was particularly difficult for Evans. Someone had been alone and without care long enough that maggots were present when she and her partner responded.

"Some of them are really hard on you, like when the patients want to scream ‘Help me,’ all the way to the hospital. ..." Evans said. "Now the top of my list of what’s hard on me is ‘Help me, help me,’ and full of maggots. That one was not my favorite experience this morning."

EMTs and paramedics often see people at their very worst — those in the midst of a mental health crisis, those who are gravely injured or near death, those whose hygiene or health are beyond the scope of what society deems acceptable, those who some would consider beyond help.

Even when their patients are unconscious or not entirely aware of their surroundings, or in a private room where only medical providers are present, Evans and her colleagues take care to ensure the comfort and dignity of the people they treat, adjusting clothing that slips during treatment, offering reassurance in response to a cry of pain.

That kindness isn't always returned — Evans said she's seen the number of combative patients increase since starting with EMS. Patterson acknowledged that the summer time can be especially difficult for his teams.

“The shifts are longer, this time of year it’s hot, people aren’t as nice as they could be. It can be stressful, right, and what we see is difficult. What these EMS providers see and do every day, most human beings aren’t wired to see those kind of things and they do it day-in and day-out, and it does take a toll, whether we want to admit it or not," he said. "I think previously, it was kind of a badge of honor of 'Yeah, I can deal with this no problem.' The reality is it will take some type of toll on all of us."

An American Ambulance Association survey found that in 2024, the turnover rate for full-time EMTs was 27% and 20% for full-time paramedics. While the rate includes both resignations and firings, nearly all of the EMTs and paramedics left their jobs voluntarily. The numbers have gone down somewhat — turnover was at 30% for full-time EMTs and 34% for full-time paramedics in 2023 — but they have consistently remained high since AAA began doing the survey in 2017. The survey also found that more than a third of those who planned to leave did so within their first year.

For many of those that do make it through in rural areas, there's no guarantee that they will stay. In the past, WCAD's clinical practice chief Doug Anderson has found that rural districts are sometimes a relatively short stop for people early in their career. Those in leadership are supportive of their teams seeking education to improve their knowledge, but the short-term employees can make it difficult to maintain a crew.

"A lot of people use it as a stepping stone but don’t stay long term because since we’re rural, we’re poor. We can’t pay them great, crazy wages like the St. Louis area departments can. We’ve seen a lot of that," Anderson said. "People will come through our programs and stick around for a few years to gain experience and certifications, and then step into a higher-paying role."

Williams, the student in Potosi, hopes that in five years she'll still be in rural setting, but with two young kids, it's uncertain, because "I do feel like I miss a lot of" them growing up due to the long shifts.

"I actually really do love the job. I love being able to help people," she said. "I love working in the rural setting because you have to know your skills in order to help save people. I love the challenge."