Pacific Islanders Can’t Return Home During COVID-19 — Even To Bury Their Loved Ones

This article is part of a larger project by Anita Hofschneider, produced with support from the 2020 National Fellowship and a grant from the Dennis A. Hunt Fund for Health Journalism.

Her other stories include:

Community Leaders: State Is Failing Pacific Islanders In The Pandemic

Hawaii's Pandemic: Hardest Hit Communities Part 1: Hawaii Wanted To Save Insurance Money. People Died

Hawaii's Pandemic: Hardest Hit Communities Part 2: Health Officials Knew COVID-19 Would Hit Pacific Islanders Hard. The State Still Fell Short

Hawaii Researchers: State Must Support Pacific Islanders In The Pandemic

Pacific Islanders Have The Highest COVID-19 Death Rate In Hawaii

Women Were Already Struggling At Work. The Pandemic Is Making It Worse

Here’s What Honolulu Is Doing To Test Hard-Hit Communities For COVID-19

Kalihi Has The Worst COVID-19 Outbreak In Hawaii. Here’s How The Community Is Responding

Hawaii COVID-19 Data For Race And Ethnicity Is Missing

Hawaii Pacific Islanders Are Twice As Likely To Be Hospitalized For COVID-19

Hawaii's Pandemic: Hardest Hit Communities Part 4: The Pandemic Is Hitting Hawaii’s Filipino Community Hard

Fresh earth covers the grave of Neita Bolkeim at Hawaiian Memorial Park in Kaneohe.

Rodrigo Mauricio knew that his wife Mary was going to die. For a decade, he had watched her diabetes worsen and her kidneys weaken. He had ushered in 2020 with her in the hospital. He had read the pamphlets from Island Hospice about what to expect when the end came.

On the day Mary died, April 1 of this year, the sun was pressing against heavy cloud cover in Palolo Valley. Mary was at home, in a bed the family had set up in the living room of the house she and Rodrigo had bought three decades before when they moved to Honolulu from Pohnpei.

All twelve of their children were present: 10 in person, two from Pohnpei via Facebook video. The family sang church songs to Mary, coaxed her to eat salted lemons, wept as her breathing slowed.

Rodrigo watched as time stretched between each of her breaths. Inhale, exhale. He waited for another breath that never came. Even though he knew what was happening, he felt overwhelmed with shock.

Somewhere in his immense grief, he also felt relief. Now, finally, the woman he loved would no longer be in pain.

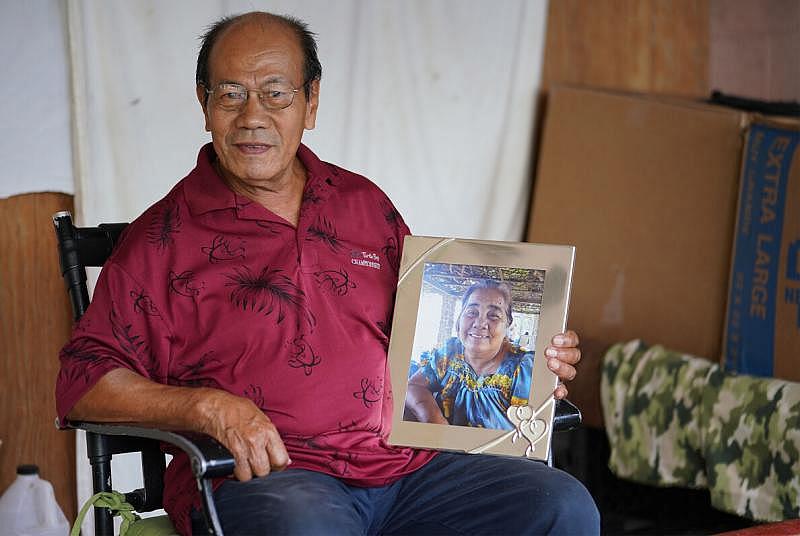

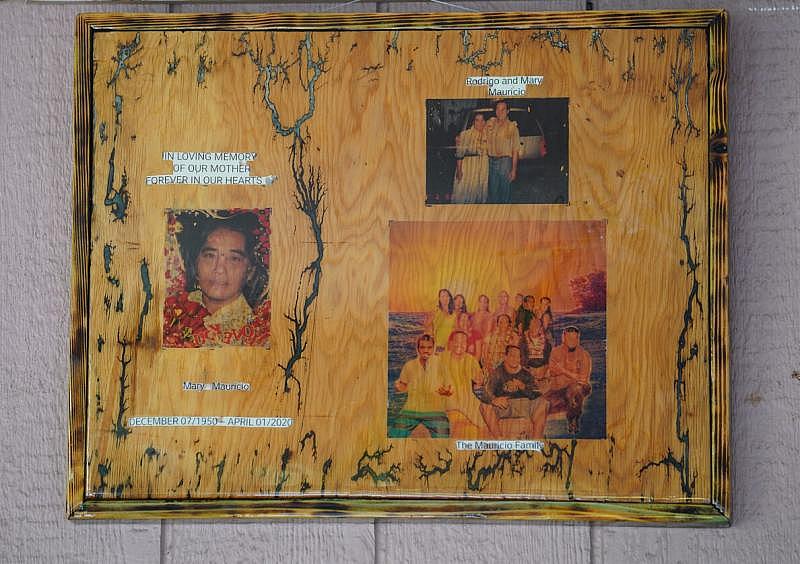

Rodrigo Mauricio and his late wife Mary were high school sweethearts in Pohnpei. Their marriage spanned over half a century.

But there was a new challenge to contend with: The world was descending into a fast-moving pandemic. If it hadn’t been for COVID-19, the family’s home would have been inundated with visitors praying the rosary. Mary’s body would have been sent to a Honolulu mortuary and then flown to Pohnpei, so she could be buried in her ancestral homeland alongside her mother and father.

Instead, seven months after her death, Mary’s body remains at a Honolulu mortuary. And the Mauricios remain in limbo, praying that they can soon accompany her home.

In her Pohnpeian community, Mary was an esteemed matriarch: the leader and last of her generation in a clan consisting of hundreds of members. Until she is buried, her clan cannot bestow her title upon another, Rodrigo explains.

He believes she is trapped in lahngepwek, heaven on earth, unable to ascend to lahngapap, heaven in the sky.

“I worry every day because she is still not at rest,” he says.

Border Closures

Pacific Islanders in Hawaii have been hit harder by COVID-19 than any other group, with Micronesians catching the virus at rates far higher than average.

The Federated States of Micronesia, like many smaller island nations, is not equipped to handle a COVID-19 surge in its population. Until this summer the FSM had no ventilators — and while it now has 30 on hand, it still lacks staff trained in the machines.

But even families like the Mauricios, which have so far managed to elude the virus itself, have been struck by pandemic-related restrictions.

Fewer than a dozen countries in the world have managed to keep the virus out, the vast majority of them in Oceania. They’ve succeeded by imposing drastic border closures that prevent even their own citizens from returning.

Efforts to repatriate citizens have been slow due to well-founded fears that the coronavirus would overwhelm limited medical facilities.

Richard Clark, spokesman for the president of the Federated States of Micronesia, estimates as many as 800 citizens are waiting to re-enter, including cancer patients and students. He said the struggle of their people trapped outside the country weighs heavily on the country’s leaders.

Rodrigo and Mary initially moved to Honolulu for his job. But when Mary got sick, life in Hawaii — with its many doctors and hospitals — became a necessity.

Now the same lack of hospital infrastructure that’s helped to fuel the Micronesian diaspora is preventing some from going home even in death, as border closures prompted by the pandemic impede the long-held tradition of burying bodies in ancestral lands.

Only one airline currently flies between the United States and Micronesia: United. Bodies can be flown on the airline’s “island hopper” flight, which stops en route between Honolulu and Guam in the Marshall Islands and across the FSM, in Chuuk, Pohnpei and Kosrae. But since the pandemic, only one or two such flights operate per month, and on most islands passengers can’t disembark.

"In our belief, we know we should be buried with our family."

Borden “Mino” Bolkeim, who moved from the Marshall Islands to Hawaii decades ago, works part time directing funerals at a Honolulu mortuary. About a third of the mortuary’s clients are Micronesian, he says, many of them Marshallese.

Under current Marshall Islands restrictions, bodies can be sent to the country but family members are not allowed to accompany them. Since March, Bolkeim hasn’t encountered a single family that was willing to send a deceased loved one home unaccompanied.

For Bolkeim, the situation is personal: His mother Neita died last month from cancer, and if he had followed tradition, he would have flown her body to Majuro and buried her next to her parents on family land on the coral atoll. Instead, she is buried in the shadow of the Koolau mountains, surrounded by the graves of strangers.

“It was hard because we know this is not our island,” he says. “In our belief, we know we should be buried with our family.”

Listen to Bolkeim explain Marshallese burial traditions.

The Path To Lahngapap

If the border to Pohnpei were open, Rodrigo Mauricio knows exactly what he would do. He would fly from Honolulu to Pohnpei, where he would put his wife’s casket in the bed of a pickup truck and drive away from the airport down a two-lane road bordered by the ocean.

He would drive through the village of Kolonia, with its churches and ball field, headed for his wife’s family’s land, more than a dozen acres dotted with breadfruit and banana trees.

That night, his family would stay up all night praying and mourning in the white-and-green concrete house where he and Mary used to live.

The next day, the family would place Mary’s coffin in the ground behind the house, next to her brother’s grave. They would press down the dirt with their hands and feet, securing her body in the earth, lining the grave with stones.

Mark Edward Harris/Civil Beat

The following day, as Mary’s body settled, the family would feast and honor the woman taking Mary’s place as the leader of the clan. They would eat white yams and drink sakau, known in Hawaii as awa.

On the morning of the third day, some family members would accompany Mary’s soul to the ocean. There they would fish. Others would stay home and compose songs, chants and rhythms to honor Mary’s life. When those who had gone to the ocean to fish returned, the pounding of the sakau root would welcome them in with their catch.

That night the family would dance, sing, eat and drink together, and at midnight they would hear a knock at the front door of the house — the sound of Mary’s soul departing the earth forever. The family would grieve again, knowing that she was truly gone.

On the fourth day, the family would have a final meal and sakau ceremony. Everyone would rub coconut oil on their bodies. Then someone would dispose of the grated coconut in the ocean or a river and most family members would leave. Rodrigo would stay and continue to grieve until the 10th day.

"The soul is in the ocean swimming and getting cleaned up before the soul is ready to go to lahngapap." — Rodrigo Mauricio

Listen to Rodrigo Mauricio describe Mary's journey to lahngapap.

Rising Costs

With United’s island hopper flights now reduced, families who are longing to return the bodies of loved ones to Micronesia may also opt to fly them on more frequent direct flights between Honolulu and Guam; from Guam, bodies are then flown to the FSM on United cargo flights.

Faithe San Agustin Escalona runs a funeral home in Guam. She usually only sees about a dozen bodies from Honolulu each year on their way to Chuuk. But that number has tripled in the last three to four months, she said, most of them victims of COVID-19.

Each United flight from Honolulu to Guam carries a maximum of two deceased individuals.

She estimates there is now a monthlong wait to send a body to Chuuk from Guam. United recently doubled the number of bodies allowed per flight to meet demand, but Escalona doesn’t think that’s enough.

“I was relieved I had five out (to Chuuk),” Escalona said recently, “but in the last week I got five more.”

Since United absorbed Micronesia’s previous sole carrier from the U.S., Continental, a decade ago, airline service to the region has declined and costs have gone up. And the pandemic has only made things worse; a spokesman for United says the company has sharply decreased its flights and laid off 16,000 employees this year.

A flight from Honolulu to Majuro takes just over five hours, but a roundtrip ticket can now cost $1,600. The pandemic wasn’t the only factor driving Bolkeim to bury his mother in Hawaii.

Nearly all of Bolkeim’s siblings live in Hawaii, and given United’s monopoly and the high cost of flying, Bolkeim knows they would rarely be able to visit their mother’s grave if she were buried at home — he hasn’t been able to visit his father’s grave for nearly two decades.

Sending loved ones’ remains home has gotten more expensive, too, with rising cargo fees. By the time mortuary fees are paid and airline tickets are bought, it can cost more than $10,000 to accompany a loved one’s body home.

“To tell you the truth, we cannot afford it, but because of our culture we find all means that we are able to to send our remains and some of us back there,” said Excuse Sananap, a Kalihi resident who was born and raised in Chuuk.

Extended family members will pitch in, even if it means coming up short on other bills. Some clans even have savings accounts specifically to help with burials.

But some families do decide the cost is too high. Honolulu resident Josie Howard said her mother Isabel Rosokow was strict about following Chuukese customs when she was alive, but near the end of her life, she surprised her children by asking to be cremated.

“She saw the struggle of our people here and she didn’t want to burden anyone,” says Howard.

Howard and her siblings asked their mother to explain her wishes to her own siblings before she died. That helped, but for years Howard didn’t feel comfortable sharing her family’s decision publicly, worried about how her mother would be perceived.

Trying To Get Home

In mid-June, Paulina Perman and her family gathered in their Makiki high rise apartment to pray another evening rosary for her father, Paulus, who had died of a non-COVID illness the month before.

Paulina’s mother Lorenza led the prayers, clutching the brown beads in her hands as she lay in bed. The fan above her was still. Honolulu nights feel cold to Lorenza after growing up in Pohnpei, which is much closer to the equator. The sliding glass door to the lanai was open, and her melodic voice carried over the hum of the nearby freeway.

Two years earlier, Paulina gave up her government job in Oregon to move to Hawaii to join her parents and care for her father. When Paulus’ doctor told him in March that he was terminally ill, he had only one request: to die on Pohnpei. But the borders shut before he could get there.

He died in this room, surrounded by family, including many in Pohnpei and the U.S. mainland who joined the rosary on FaceTime. They watched him take his last breath and sobbed, but Paulina and Lorenza did not break the rhythm of their recitations. They hoped their prayers would carry him to heaven.

The pain of losing him has been compounded by the endless uncertainty of when they might be able to accompany his body home. Paulina created an online petition to try to convince her island government to allow the family to bring him home. She started a Facebook group called, “No one left behind. For the love of our stranded <3.”

Last month Lorenza flew to Guam, hoping from there to be able to board the first scheduled flight to Pohnpei. That flight was postponed, and now Lorenza’s hoping to leave Guam for Pohnpei in December. But even if she succeeds in getting home, it’s unclear when Paulina will be able to join her and bring Paulus’ body from Honolulu.

Many already within the FSM are feeling grief, too. Moses Pretrick, the FSM’s assistant secretary of health and social affairs, said he has had two relatives in the U.S. die this year for non-COVID reasons. In part due to border closures, they were cremated.

"Everyone is so desperate and waiting and waiting."

- Paulina Perman and her daughter Leea Mengidab

Listen to the Perman family sing a song that Paulus Perman sang before he died.

‘She Is The Motherland’

If Mary had died of the coronavirus, Rodrigo would have had to cremate her to send her home. Unlike other states in the FSM, Pohnpei isn’t accepting the bodies of people who contracted COVID-19.

In this way, Rodrigo is lucky. And if he wanted to, under current FSM rules, he could send Mary’s coffin through Guam, on the cargo flights that are still delivering medicine, mail and other essential supplies throughout the region.

His two children could receive her. But he worries that his children, who grew up in Honolulu, wouldn’t be able to perform the ceremonies properly without him.

“She deserves the honor to be properly buried,” he said.

Women are different.

“She is part of the motherland. She is the mother,” he said. “She is the motherland.”

It’s unclear what Rodrigo’s persistence will ultimately cost him. He has already spent thousands of dollars to preserve and store Mary’s body. United raised its flight prices further in July.

Rodrigo’s greatest fear is that he might catch COVID-19 and die before he has the chance to bury her.

“I think to myself, I really need to be alive and bury my wife, so I am very cautious,” he says, speaking through a face shield.

He remembers how much Mary loved their children, how she wanted to stay in Hawaii to be closer to them despite missing Pohnpei, how she overcame her shyness to speak English and take a job working in the laundromat in Market City. She and Rodrigo were married for more than 50 years.

Before she died, he promised he would take her back. It’s a promise he will do everything he can to keep.

This story was produced with support from the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism National Fellowship and its Dennis A. Hunt Fund for Health Journalism.

[This story was originally published by Civil Beat and Samoa News.]