Part 2: Provo Canyon School’s history of abuse accusations spans decades, far beyond Paris Hilton

This story was produced as part of a larger project by Jessica Miller, a participant in the 2019 Data Fellowship. It focuses on the troubled rehabilitation industry in Utah, where youth residential treatment centers are abundant but lack adequate oversight.

Also in this series:

Paris Hilton says she was abused while at Utah facility for ‘troubled teens’

Paris Hilton creates petition to shut down Provo Canyon School

Paris Hilton leads rally against Provo Canyon School

Why we raised money to get reports on Utah’s ‘troubled teen’ treatment centers

Part 3: Utah faces criticism for its light oversight of ‘troubled teen’ treatment centers

Part 4: Former students at Utah troubled-teen centers say their reports of sex abuse were ignored

Utah inspectors find no problems in ‘troubled-teen’ facilities 98% of the time

Increased oversight is coming to Utah’s ‘troubled-teen’ industry

A girl, her hands zip tied, was forced to sit in a horse trough at a Utah ‘troubled-teen’ center

Utah officials want your help as they draft new rules for the ‘troubled-teen’ industry

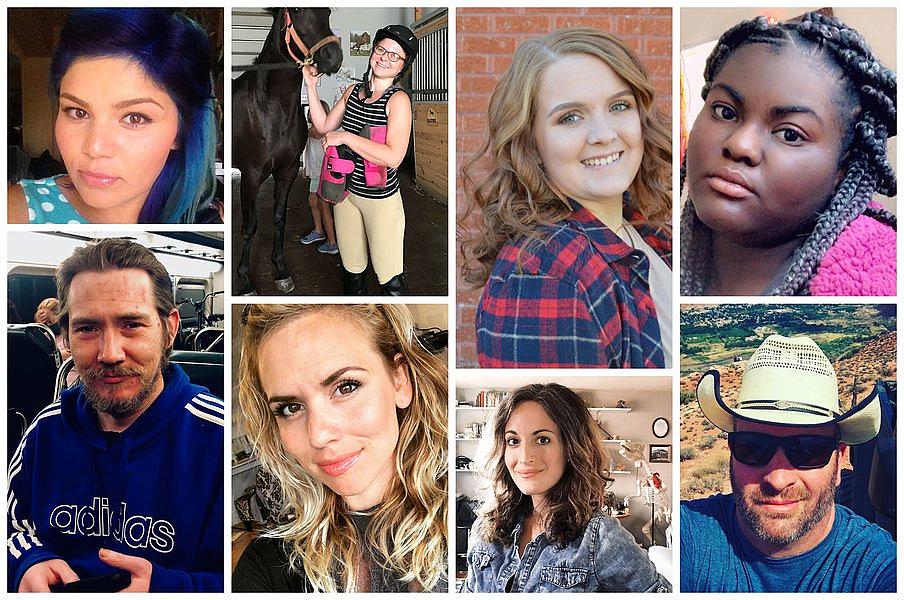

Several former enrollees of Provo Canyon School for troubled teens describe mistreatment that ranged from isolation to use of restraints and medication. Shown are, top row from left, Sarah Stevenson, Elizabeth Abeyesekera, Kylee Havey and Kayla Smith; Bottom row from left, Aaron Morris, Kyra Lewis, Jen Robison and Jeremy Whiteley.

When celebrity Paris Hilton went public recently with allegations that she was physically and mentally abused at Provo Canyon School in the 1990s, the treatment facility’s owner quickly brushed off responsibility.

Universal Health Services didn’t own or run the school then, so it said it couldn’t weigh in on what Hilton says happened to her.

But people who were residents at Provo Canyon School in recent years have made similar accusations. There is a pattern of controversy and allegations of abuse that stretches from the 1980s to today at one of Utah’s largest youth residential treatment centers.

Eight former students whose stays spanned decades told The Salt Lake Tribune about their experiences at three of the four campuses that have operated as Provo Canyon School.

They spoke of repeated physical restraints, with up to 10 staffers piling on young children. Some were chemically sedated, or so overmedicated they felt like a zombie. Others spoke of being left in isolation rooms for days after getting in trouble for things like not getting out of bed or asking for an inhaler.

Provo Canyon School has remained operational for nearly 50 years — despite multiple lawsuits, a company bankruptcy, state threats to pull its license, and public accounts of abuse from young people who were sent there.

Former students are once again speaking out about their experiences at the Utah residential treatment center after Hilton, an heiress to the Hilton hotel fortune and a reality television star, released a documentary last week detailing her experiences.

Like Hilton, they hope sharing their stories will lead to changes in the way young people are treated at Provo Canyon School and similar places.

“I don’t know if my nightmares are ever going to go away,” Hilton said in the film, released on YouTube. “But I do know there are probably hundreds of thousands of kids going through the same thing right now. And maybe if I can help stop their nightmares, it will help stop mine.”

Early days

Provo Canyon School opened its first facility for boys in 1971 and got into legal trouble just a few years later.

Two teens sent there by their home state’s juvenile justice system ran away — one was from Alaska, the other from Nevada — and sought protection from the federal courts. They filed a lawsuit against the original owners, Jack Williams and Robert Crist, challenging the school’s education, treatment and confinement methods.

Jurors returned a verdict favoring Provo Canyon School after a lengthy trial in 1980, but a federal judge issued a permanent injunction banning the school from using polygraph tests on the boys, opening and reading their mail, using isolation for any reason other than to contain a boy who was violent, and prohibited physical force from being used to restrain a boy unless he was an immediate danger to himself or others.

A few years later, in 1986, Charter Behavioral Health Systems bought the original Provo campus. The company, once the nation’s largest operator of psychiatric hospitals and treatment centers, would own the school for the next 14 years.

It was during this time, in 1989, that Jeremy Whiteley was enrolled. He was 15 at the time, a self-described “normal teenager” from Washington who was “going through a rebellious cycle.” His parents and therapist asked if he’d like to try a boarding school, a place in Utah where he could hike and ski and be outdoors.

“I went willingly,” he recalled. “My dad took me. And basically, after I said goodbye, that’s when the nightmare started. It wasn’t at all what was described to me.”

Instead of playing basketball or going swimming in the pool, Whiteley said he was taken to a room and strip-searched. He remembers watching his classmates held down by staff or being injected with a sedative.

He moved quickly through the levels of the program but was knocked back down after he tried to run away during an approved visit to a family reunion in New Hampshire. His punishment involved standing up against a wall for hours on end for several weeks. Whiteley said he was prescribed so much medication, he “felt like a zombie.”

Two years later, his parents pulled him from Provo Canyon School.

“The program was a complete failure for me,” the now-46-year-old man said. “It was basically almost two years of prison.”

Whiteley burned almost every record he had from Provo Canyon School a decade later, a way of purging the bad memories. Now, one of the only physical reminders he has from that time are some textbooks with his assigned number scribbled on it: #142.

‘The worst of the worst’

Charter Behavioral Health Systems still owned Provo Canyon School in 1999, when Paris Hilton’s parents sent their 17-year-old daughter there after she was getting in trouble for sneaking out to go to clubs or parties. It was the last in a series of facilities her parents sent her to, she recalled in her documentary, “This is Paris.”

“That was the worst of the worst,” Hilton said. “There’s no getting out of there. You’re sitting on a chair and staring at a wall all day long, getting yelled at or getting hit.”

Hilton recalled in the documentary that she felt the staff enjoyed hurting children or seeing them naked as they showered. She said she and others were often overmedicated.

“I didn’t know what they were giving me,” she said. “I would just feel so tired and numb. Some people in that place were just gone. The lights were on, but no one was home.”

Hilton left 11 months later, which she described as one of the “happiest moments of my life.”

It was around this same time that Provo Canyon School’s parent company was under intense scrutiny, facing allegations of Medicaid fraud and media reports of inappropriate treatment and inadequate care at Charter-owned facilities across the country.

Charter Behavioral Health Systems filed for bankruptcy in 2000, and several months later sold a dozen properties — including Provo Canyon School — to Universal Health Services.

The acquisitions bolstered the UHS portfolio. It is now one of the largest hospital providers in the nation. The Pennsylvania-based company netted $11.37 billion in annual revenue in 2019, according to its finance forms.

Continued allegations of abuse

The allegations of abuse and mistreatment haven’t stopped in the two decades that UHS has owned Provo Canyon School.

Six women who went there between 2003 and 2017 told The Tribune similar stories of being overmedicated, restrained and punished for minor infractions while at the girls campuses in Springville and Orem.

Kayla Smith was 8 years old when her parents, in coordination with her California school district, sent her to Utah in 2010.

She’s 19 now, but she still feels a tension in her chest as she talks about her time there.

Smith recalled being strip-searched and touched by staff, an experience that was foggy to her because she had been medicated before she came. She was homesick her first night, and staff put her in an isolation room and locked her inside — which is against Utah regulatory rules, which says “timeout rooms” cannot be locked.

Smith said she was frequently given shots that made her go to sleep, something that happened if she cried while staff members held her down.

“It’s traumatizing,” she recalled of the restraints. “It’s very scary. Mostly, it just scares you more. You’re already upset. The environment is just making it worse for you.”

Staffers are allowed to physically restrain students at youth treatment facilities in Utah, but the state has rules. Staffers are not to use force as a punishment, only putting their hands on a young person if he or she “presents imminent danger to self or others.” The rules are similar for chemical restraints.

But Kyra Lewis, who came to Provo Canyon School from Alaska in 2003, said physical restraints “happened all the time” when she was there. Injections also were common and had been nicknamed “booty juice.”

Lewis said she was held down once by a staffer who slammed her to the ground as she tried to climb a fence to run away. Her experience there has caused her lasting trauma, she said.

“I still have a problem if I am touched a certain way,” Lewis said. “It scares me if someone yells at me. We have to find a way to change how we do mental health. Teenagers should not be drugged up and ignored. They are telling the truth, and their perspective is real to them.”

Adam McClain, the CEO of Provo Canyon School, would not address individual allegations because of privacy laws, and he did not answer questions about how often students are chemically restrained or whether efforts have been made to reduce the number of times students are put in restraints.

He noted in a statement that mental health treatment has evolved over the past 20 years from a “behaviors-based foundation” to a “personalized, trauma-informed approach.” He said the facility does not use solitary confinement as a form of intervention and does not use drugs or medications as a disciplinary measure.

He added that the youths they work with have complex needs and are often a danger to themselves or others.

“We are concerned that the current media coverage may increase the stigma around seeking help for behavioral health concerns,” he said. “This would be a disservice if it leads people away from seeking necessary care and increases the stigma around mental health that providers, organizations, advocates and members of the public have worked so hard — and made much progress over the years — to break.”

‘Big business’

Provo Canyon School is far from the only treatment center to face persistent allegations of abuse and mistreatment, said Ronald Davidson, who was the director of the Mental Health Policy Program at the University of Illinois at Chicago’s Department of Psychiatry for 20 years until he retired in 2014.

Davidson, a national expert on child welfare, conducted hundreds of reviews of psychiatric hospitals and residential treatment centers in a dozen states for the Illinois Department of Children and Family Services and the American Civil Liberties Union as part of a federal court consent decree.

He said he identified a recurring pattern of risk factors in certain facilities run by large for-profit corporations where Illinois had placed hundreds of children in its foster care system: Staffing levels were low, incidents of serious harm and abuse were high, children were often overmedicated and over-restrained, and the corporate owners made a lot of money.

“Exploiting troubled kids for profit is big business,” Davidson said, “and many state agencies are so desperate to find places that will take troubled children that they don’t ask too many questions or monitor the quality of care that’s supposedly being provided.”

Davidson’s investigative teams found widespread sexual abuse and evidence of harm to Illinois children during visits to out-of-state treatment centers.

“It’s not true that nobody knows how to run effective and good quality treatment programs for kids,” he said. “But when substandard programs are allowed to operate without competent oversight and monitoring, that’s a business model guaranteed to produce harm to children.”

Utah’s Office of Licensing, which provides oversight to youth residential treatment centers, has conducted 341 investigations in the past five years at Provo Canyon School’s four campuses. In these cases, regulators “substantiated” 27 violations, according to the department.

That information isn’t easy to get — not for parents considering sending their children there or state foster care programs looking to contract with the school.

The Tribune asked the Office of Licensing to release investigative records and inspection reports. The office said it would not unless the newspaper paid $2,000 for a staffer to read and redact the files. The Tribune is appealing that cost.

What is public is that regulators have noted serious violations, and Provo Canyon School has nearly lost its license several times.

It was placed on “conditional status” in 2015 after staff, on two occasions, injured students while holding them in restraints. The Provo facility was also in violation for having a seclusion room with a lock on it, according to a notice of agency action.

The Springville campus was put on conditional status in 2013 after a girl was injured in a restraint, and the Provo campus had the same agency action taken against it in 2012 after staff did not properly watch students and a boy ran away. That boy stole a car and caused a car crash in Provo that killed a 65-year-old woman.

Breaking their silence

For some former residents, seeing a celebrity like Hilton speaking out has motivated them to also share their stories.

Jen Robison, who went to Provo Canyon School in 2003, helped start a growing movement four years ago called Breaking Code Silence, an online platform where people talk about what they endured at facilities across the country.

Their goal, Robison said, is to bring more awareness to the massive industry in Utah — where nearly 100 facilities operate — and elsewhere.

“For me, it’s the turning of the table,” Robison said. “I refuse to be a victim. I want to be someone who can stand for others who have been victimized in their life.”

Robison was 14 when she came to Provo Canyon School, sent by her parents as she struggled with depression.

But she said she left more damaged than when she got there, and it took years before she was able to recognize the effect it had on her and to heal from it.

“The thing that still haunts me is the amount of time in isolation,” she said, “being left in that room for so long, watching other girls being restrained and shot up with Haldol. It’s still something I don’t know how to reconcile with the rest of my life.”

Robison said she hopes that people will listen to her story and those from others who were there and put pressure on officials to change the laws and increase the amount of regulation on this industry.

“It’s been healing for me to be able to work with other survivors,” she said, “and hopefully change this for the next generations.”

Correction: Sept. 20, 2020: The Utah Office of Licensing estimated it would cost $2,000 for a staffer to redact 341 investigative reports and inspection reports. A previous version of this story misstated that the cost estimate was for the 27 investigations where violations were "substantiated."

[Tell The Tribune: What’s your experience with Utah’s ‘troubled teen’ industry?]

[This story was originally published by The Salt Lake Tribune.]