Most Kentucky public schools don’t follow emergency planning law, leaving athletes at risk

The story was originally published in The Courier Journal with support from our 2022 Data Fellowship.

Matthew Mangine Jr. died in 2020 after he collapsed on the soccer pitch during the team's first off-season conditioning.

MATTHEW MANGINE JR. FOUNDATION

UNION, Ky. ― Matthew Mangine Jr. felt back where he belonged ― on the soccer field.

His cleats dug into the grass as he ran with his teammates at the end of their first preseason conditioning.

It was June 16, 2020, the day after Kentucky lifted its COVID-19 sports shutdown.

The 16-year-old was running his final sprint when he dropped to his knees.

His coach called 911.

His mom, Kim, was in the parking lot talking with another parent. When she saw the commotion surrounding her oldest son, she began running.

Another parent was sent to find the athletic trainer, who was at the girls’ soccer practice at the other end of the school, on the far west side of campus.

No one phoned the athletic trainer to tell him there was an emergency.

No one ran for a defibrillator.

No one had a plan for what to do.

Matthew began to gasp. It’s what’s known as “agonal breathing” because it sounds like pure agony.

Based on the start time of the 911 call and the sheriff's body camera footage, at least 12 minutes passed between Matthew’s collapse and the shock delivered by an EMS defibrillator (AED).

“For every minute that passes, your chance of survival decreases by 10%,” said Samantha Scarneo-Miller, who studies sudden death in sports.

The clock ran out on Matthew Mangine Jr.

A plan for when the worst happens

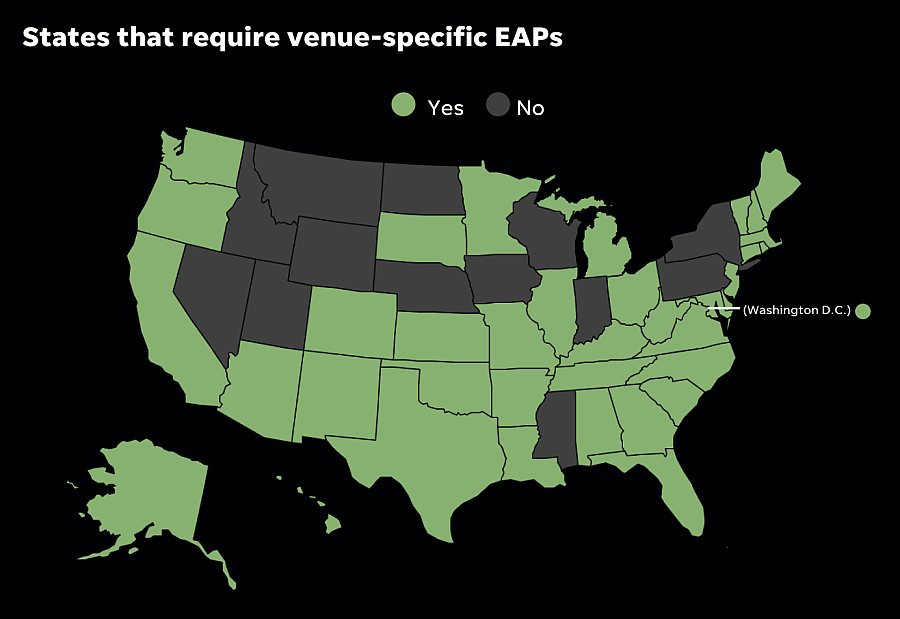

Kentucky is one of 37 states requiring schools to have plans for what to do in a sports-related emergency.

These emergency action plans, or EAPs, are meant to be tailored for different sports venues.

“The reason it’s venue-specific is it’s not going to be boilerplate,” said Kentucky High School Athletic Association commissioner Julian Tackett. “My EAP at a 6,000-yard, 18-hole golf course might look different than my 3,000-meter cross-country course (which) might look different than my baseball field.”

Based on state laws and/or state athletic association requirements

SOURCE Korey Stringer Institute

CPR certifications for coaches became law in Kentucky following the 2008 heat stroke death of Louisville high school football player Max Gilpin. A few years later, the teenager’s death played a role in the passage of the venue-specific EAP law.

The KHSAA followed up by requiring its member schools, which includes private schools, to have the plans.

But, as with the CPR certifications, the athletic association doesn’t check for EAPs. That’s left up to school districts.

My EAP at a 6,000-yard, 18-hole golf course might look different than my 3,000-meter cross-country course (which) might look different than my baseball field.

Julian Tackett, Kentucky High School Athletic Association commissioner

As part of a seven-month investigation into high school sports safety, The Courier Journal gathered all available EAPs in Kentucky and found routine failure by schools to comply with all aspects of the 11-year-old law.

And there is no enforcement mechanism or punishment built into the law or KHSAA policy for those who don’t comply.

"It’s a little hard because we are extremely local-control oriented in this state," Tackett said. "Its policies are built for local control. It’s not built for autocracy. It’s built for 'we’ll give you the best ideas, and you implement them.'

"And local control is not very pretty sometimes when you look at who is doing what and where."

Grading Kentucky’s plans to keep sidelines safe

When the venue-specific EAP portion of Kentucky’s law went into effect in 2012, it required plans for exactly what to do in the event of an athletic emergency after the school bell rings.

The law called for the EAPs to:

- Be in writing;

- Include a delineation of roles;

- Include methods of communication;

- Include available emergency response equipment;

- Include access to/plan for emergency transportation;

- Be rehearsed annually by all athletic trainers, first responders, coaches, nurses, athletic directors and athletic volunteers;

- Be reviewed by the school principal;

- Be submitted annually to the state or athletic association.

The Courier Journal requested every venue-specific EAP for KHSAA-member high schools for the current school year. All but two of the 233 public high schools responded.

Then, we asked Scarneo-Miller and her West Virginia University athletic training masters-level students to review each one against the requirements of the law.

"We took the state law verbatim, put it into a checklist," Scarneo-Miller said. "So, we were looking for deliberate and intentional language in the checklist."

West Virginia University professor Samantha Scarneo-Miller and her masters-level students talk during a video call with a Courier Journal reporter as they review all venue-specific athletic emergency action plans for public schools in Kentucky.

Video Capture

Through the responses, they were able to track six of the law's eight components.

Here's what they found:

- 23% of schools were likely following all six parts of the law;

- 31% of schools were likely following five out of six;

- 24% of schools were likely following four;

- 10% of schools were likely following half of the parts of the law;

- 5% of schools were likely following two;

- 3% of schools were likely following just one part of the law;

- 4% of schools weren't likely following any parts of the law.

Kentucky’s law says school principals must annually review EAPs for each sports venue. But the law doesn’t require documentation for that.

The same goes for the requirement that plans be rehearsed annually ― no documentation necessary. So, those two components were unable to be evaluated.

Scarneo-Miller said these are shortcomings of the law.

It was pretty astonishing to see how many schools did not have the components that are in the Kentucky state law.

Samantha Scarneo-Miller, an athletic emergency response expert at West Virginia University

"It was pretty astonishing to see how many schools did not have the components that are in the Kentucky state law," Scareno-Miller said.

Kentucky’s newest safety law, approved in March, focuses on written cardiac response plans and simulated rehearsals of cardiac arrest drills. It recommends, but doesn't require, AEDs for all middle and high schools.

The new law requires the written plan be discussed on the first instructional day of each school year, as well as documentation of that discussion. It does not require documentation for the rehearsals that are to take place prior to every sports season.

Like the venue-specific EAP law, the new law has no enforcement mechanism or punishment for those who don’t comply.

It’s unclear whether the new law will become KHSAA policy, like the EAP law.

The KHSAA policy doesn’t mimic the state law for EAPs, though. One notable change is that it removes language that each school must submit a yearly verification to the association confirming its plan exists.

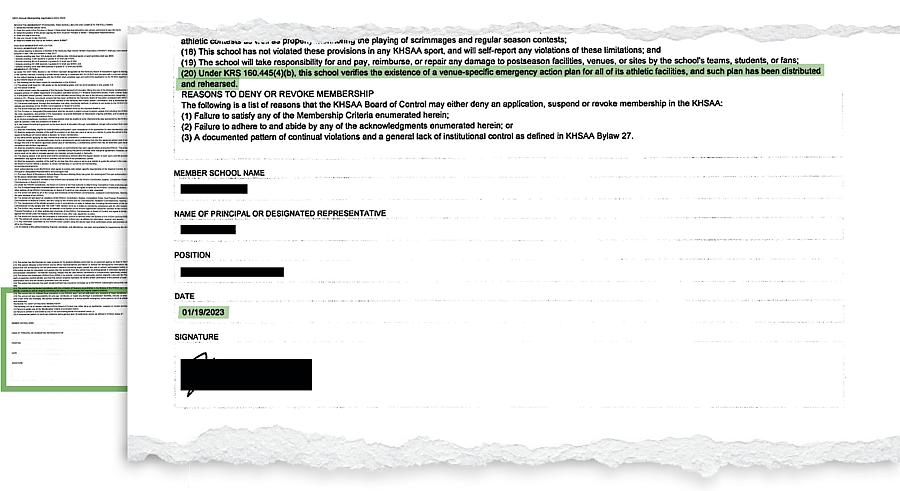

Still, schools are supposed to annually certify their plan's existence by signing the KHSAA’s yearly membership application.

By signing it, they agree to 20 items, including the presence of a venue-specific EAP, and in return are eligible to compete in the postseason and are covered by the KHSAA’s catastrophic injury insurance.

But no one at the KHSAA checks to make sure plans are specific to each school’s athletic venues.

“… We don’t have facility specialists,” Tackett said about the KHSAA’s role in venue-specific EAPs. “We can’t go out and say, 'Well your plan is good at this golf course, but your plan is not.’ That’s not the expertise here.

“It’s certainly not the risk that a little non-profit group can take.”

The Courier Journal also requested these annual verifications from high schools and found:

- Two schools didn't know the membership application existed prior to The Courier Journal's email;

- Ten schools were unable to locate records for the 2021-22 season;

- At least a half-dozen schools had not submitted the annual verification, but had paid their KHSAA dues;

- Another dozen schools didn’t fill out the annual membership application for the 2022-23 season until after The Courier Journal asked for the records.

The Courier Journal requested KHSAA annual membership applications from all Kentucky public schools because it certifies, under the law, schools have venue-specific EAPs for all facilities for each school year. This 2022-23 document is one of a dozen dated after The Courier Journal requested the applications on Jan. 18, 2023.

KYLE SLAGLE/USA TODAY NETWORK

“I do not have any previous years’ (verifications) because we never had to fill them out,” a McLean County school administrator said in an email. “The previous AD just paid the (dues) bill.”

A representative from Robertson County Schools said in an email they don't submit the form annually, either. They did submit one following The Courier Journal's request, saying: "We were not aware of this form previously and will be sure to complete from this point forward."

Louisville’s Pleasure Ridge Park High School was one of the schools that didn’t complete its verification for the 2021-22 school year.

That’s the school where football player Max Gilpin suffered heat stroke and died in 2008.

Pleasure Ridge Park football player Max Gilpin suffered a fatal heat stroke in 2008. Gilpin collapsed on a nearby practice field. Photo: April 9, 2023.

MICHAEL CLEVENGER AND SCOTT UTTERBACK/COURIER JOURNAL

‘Our beautiful, firstborn son’

St. Henry District High School athletic trainer Mike Bowling sent venue-specific EAPs to the school’s then-acting athletic director, Maureen Kaiser, nine days before Matthew Mangine Jr. collapsed on the soccer field.

In a deposition, she said she “glanced over them.”

More than a year after Mangine’s death, school Principal David Gish said in his deposition he had “not seen or read” the Erlanger school’s EAPs.

There was no EAP for the practice field where Matthew collapsed.

The plans that Bowling did create listed only three AEDs. There were five ― four in the school and one that stayed with Bowling.

So, the coaches didn't know the closest one to Matt was 275 feet away, behind a locked door just off the soccer field. And even if they did, they didn't have keys to the lock.

When Bowling arrived on the scene, he never grabbed the AED out of his car.

"There were five AEDs on campus, yet no one retrieved an AED to apply to Matthew due to lack of proper training, and because the coach was never given an emergency action plan, nor told where the nearest AED was," said Matthew Mangine Sr. of Union, Kentucky.

A view of the side of St. Henry District High School from the practice field where Matthew Mangine Jr. collapsed. The closest AED was behind the door furthest to the right, about 275 feet from where Matthew went down.

MURPHY LANDEN JONES PLLC

A view of the side of St. Henry District High School from the practice field where Matthew Mangine Jr. collapsed. The closest AED was behind the door furthest to the right, about 275 feet from where Matthew went down

MURPHY LANDEN JONES PLLC

An AED hangs on the wall in the school hallway.

MURPHY LANDEN JONES PLLC

"By the time the ambulance arrived, it was too late. We lost our beautiful firstborn son."

Asked for comment, the Diocese of Covington, which oversees St. Henry District High, re-issued a past statement that says, "Matt Mangine was a loved and respected student, athlete, and friend. Our faith community continues to grieve for him."

Who was supposed to do what and when? Those questions play out in a series of finger-pointing in the depositions brought on by the Mangine family's wrongful-death lawsuit, which settled in January.

Matthew Mangine Jr. and a friend are all smiles before Homecoming 2019. Mangine collapsed during soccer conditioning in June 2020 in Erlanger, Kentucky.

MATTHEW MANGINE SR.

"Matthew's death exposed the refusal of state administrators and legislators to admit that the lax nature of the so-called 'requirements' of (the EAP law) and the KHSAA are causing Kentucky school children to be at risk," said Kevin Murphy, the lead attorney for the family. "Why? No accountability and no fear of punishment."

By the time the ambulance arrived, it was too late. We lost our beautiful firstborn son.

Matthew Mangine Sr.

Kim and Matthew Sr. are left with an untouched room at the top of the stairs. It's bathed in a purple light. They never turn it off. It was Matthew's favorite color.

Matthew's death has taken the family in a new direction. They offer CPR and AED training to schools through a foundation set up in their son's honor. And they're fighting for legislation, both state and federal.

"This issue is not blue or red," Mangine Sr. said at the statehouse in Kentucky and again on Capitol Hill. "This issue is purple."

Today, you can spot them at sporting events for their youngest son, Joseph. They always carry a backpack. Tucked inside is an AED, the life-saving device they're prepared to use on someone else's loved one. It's a way of carrying Matthew with them, Mangine Sr. said.

"The only thing left to do is speak for him."

Reach Stephanie Kuzydym at skuzydym@courier-journal.com. Follow her for updates to Safer Sidelines on Twitter at @stephkuzy.