Solutions for youth sports safety: How one state used data to make a difference.

The story was originally published in The Courier Journal with support from our 2022 Data Fellowship.

Bud Cooper, a professor at the University of Georgia who researches extreme environmental conditions and its impact on exertional heat illness risk in athletes, demonstrates a wet bulb globe temperature monitor.

UNIVERSITY OF GEORGIA

The list of names slowly grew until Georgia led the nation in a terrible category: heat-related deaths of high school football players.

The state lost six players to heat in 29 years.

They lost two athletes on a single day ― Aug. 2, 2011. Forrest Jones collapsed during a voluntary workout. Donteria "DJ" Searcy was found unresponsive following a morning practice at the team’s football camp in northern Florida.

At the time, Georgia had little regulation of preseason football practice.

“It was not uncommon for a high school to go to some remote location for ‘camp’ and have the athletes participate in as many as six practice sessions in one day,” said Bud Cooper, a University of Georgia professor who studies heat’s impact on the body.

“It was all under the auspices to, ‘get my players whipped into shape and make them better athletes.’”

While at least 25 other states had heat-related deaths of football players over the same 29-year period, 1980-2009, Georgia admitted it had a problem and sought to find a solution.

Through a series of steps, in 2012 it became the first ― and still to this day, only ― state to adopt a data-driven policy to protect high school football players from heat-related illness and death.

When the recommendations are followed, we are batting a thousand.

Bud Cooper, University of Georgia professor

Heat is only one of the four main reasons why high school athletes die. The others are tied to: heart (sudden cardiac arrest), head (trauma) and hemoglobin (blood).

The Georgia High School Association, which governs athletics, asked Cooper in 2009 to study the problem. He agreed to do a three-year study to collect information and give recommendations based on the data he gathered. Searcy and Jones' death happened just before the study ended in the fall of 2011.

Based on the data, Cooper recommended they modify or remove equipment, increase hydration and rest breaks, shorten practices based on the "wet bulb globe temperature" and follow an acclimatization period to allow athletes' bodies time to adjust to the heat.

The association accepted every recommendation and hasn't had a heat-related death of a football player since putting the program in place in 2012.

Georgia solved a major piece of the health-and-safety puzzle for high school athletes, even adding fines for not following the policy.

But the 2019 heat-related death of a girls’ high school basketball player, and subsequent record-setting lawsuit, demonstrates that the policy works only if it's followed.

Imani Bell, 16, suffered a heart attack during an outdoor basketball workout in Georgia's August heat, state authorities found. The state policy says outdoor workouts shouldn't happen if the wet bulb globe temperature is over 92 degrees, though it's unclear whether it was taken that day.

The Georgia Bureau of Investigation reported the heat index that day as between 101 and 106 degrees.

"They did not follow the recommendations," Cooper said of Bell's coaches. "When the recommendations are followed, we are batting a thousand."

Nationally, many states are grappling with how to prevent youth athlete deaths, particularly in the wake of the high-profile save of Buffalo Bills safety Damar Hamlin, who went into cardiac arrest during a Monday Night Football game on Jan. 2.

According to experts, here are the main steps to take to make Hamlin’s outcome more common when the worst happens in high school and youth sports:

Wet bulb globe temperature

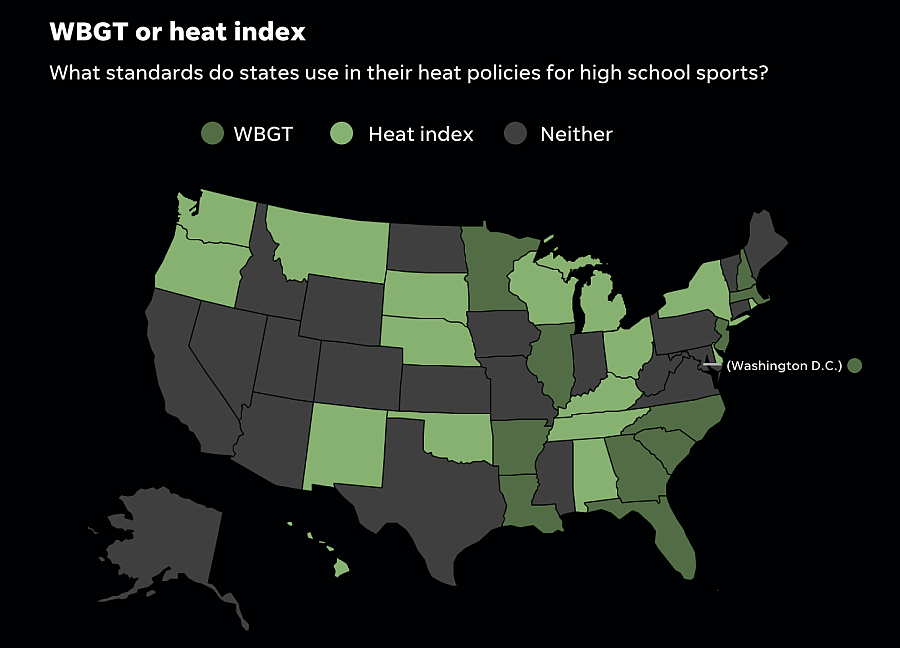

Georgia and 12 other states have moved to wet bulb globe temperature monitor when deciding whether to modify practices.

Kentucky remains one of 17 states to base its heat policy on the more commonly known “heat index,” which is a combination of air temperature and humidity.

The remaining states either have a recommendation regarding environmental monitoring or have no language at all, according to the Korey Stringer Institute, which researches sudden death in athletes.

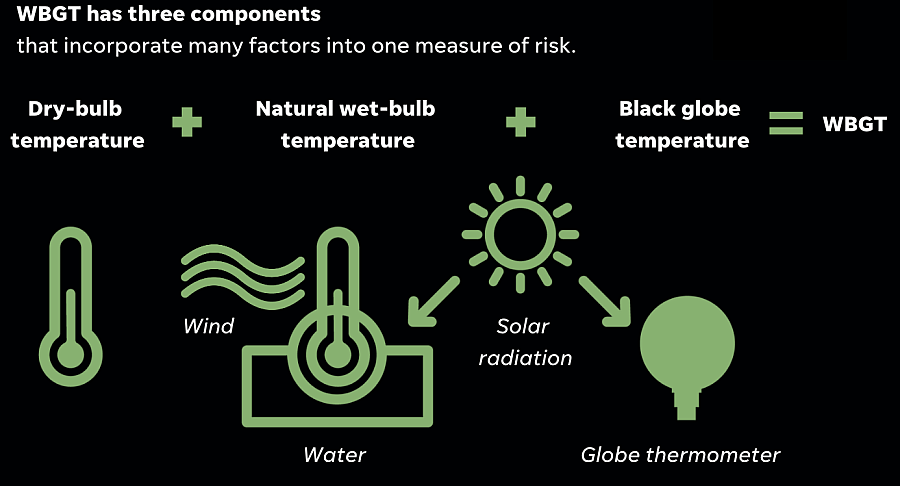

What is WBGT?

Wet Bulb Globe Temperature (WBGT) is a way to measure the heat stress on a body in direct sunlight and takes into account many different elements.

WBGT takes into account

- Temperature

- Wind speed

- Humidity

- The intensity of the sunlight (sun angle and degree of cloud cover)

Heat index is calculated in the shade and only takes into account temperature and humidity.

Like the heat index, the WBGT takes into account the temperature and humidity of the air. It also considers the effects of solar radiation (heat stress is greater in the sun) and the wind speed (heat stress is much greater when the winds are not blowing).

SOURCE Convergence of Climate-Health Vulnerabilities

Cooper said the heat index is a flawed metric when used in this situation.

“The heat index is based on a formula that looks at an individual who is 5-foot-7, weighs 150 pounds, wearing short sleeves and long pants, walking 3 miles an hour in the shade,” Cooper said. “That is not a true representation of what we see in athletics.”

Wet bulb globe temperature combines air temperature, humidity and radiant heat from the playing field in its measurement.

“When you look at the WBGT calculation, radiant heat and humidity are more heavily weighted than air temperature,” Cooper said.

In 2002, the National Athletic Trainers Association adopted WBGT as its standard for heat policies.

The measurement is also endorsed by the NCAA, the NFL, the U.S. Department of Defense, the American College of Sports Medicine and the American Pediatrics Association.

Based on state laws and/or state athletic association requirements

SOURCE Korey Stringer Institute

Athletic trainers

An athletic trainer is considered the front line of defense in sports emergency response.

Athletic trainers are educated and trained on everything from injury prevention and rehabilitation to spine boarding, CPR and defibrillator use.

“Coaches shouldn’t have to be making those decisions on providing that type of care,” said Kathy Dieringer, NATA president. “That’s what we’re here for.”

What does an athletic trainer do?

Emergency injuries and illnesses that athletic trainers are trained to treat include:

- Concussion

- Heat stroke

- Sudden cardiac arrest

- Asthma attack

- Diabetic emergenices

- Sickle cell crisis

- Spine injuries

Athletic trainers are health care professionals who collaborate with physicians to provide:

- Therapeutic intervention

- Preventative services

- Emergency care

- Clinical examination and diagnosis

- Rehabilitation of injuries and medical conditions

Nationally, just 32% of high schools have a full-time athletic trainer. Fifty-seven percent of those athletic trainers are funded by health care or university systems, while 37% are funded by a school.

The NATA has a resource called AT Your Own Risk that helps provide more information about what athletic trainers do and how to get one at your school.

Youth athletic tournaments also happen across the country without athletic trainers.

Doug Casa, the CEO of the Korey Stringer Institute, has two daughters who participate in select soccer tournaments.

“If you just had $1 per kid competing at the tournament, you could pay an athletic trainer $100 an hour to be there for the day…,” Casa said. “The cost burden would be literally miniscule when you spread it out over all the teams.”

Venue-specific emergency action plans

Schools have response plans for emergencies that might happen during the school day, but after the school bell rings, it can often be another story.

Thirty-seven states, including Kentucky, require venue-specific emergency action plans for after-school sports. Venue-specific means the plans are supposed to be tailored for different venues ― for instance, the baseball field vs. the track.

Other than the time to draft them, the policies don’t cost anything. They describe exactly what to do in case of an emergency during an athletic event.

Athletic trainers are educated on how to develop a comprehensive EAP that includes items such as available emergency equipment and coordinating with EMS.

Schools without an athletic trainer or a part-time one may need the athletic director to create emergency plans for every venue.

“There are templates ― really good templates,” Casa said. “It just requires you to disperse it, rehearse it and discuss it occasionally with your staff.”

The Korey Stringer Institute has a sample emergency action plan on its website that shows venue-specific EAPs and corresponding maps.

KSI also works with state athletic associations and schools to review their policies and plans.

“When we work with them, (schools) think they have EAP policies ... because the school does have an emergency action plan, but it’s not specific to sports,” Casa said. “These policies need to be now shaped around the sports environment and not just the school environment.”

CPR training

Are you CPR certified?

It’s OK if you’re not; you can still save a life.

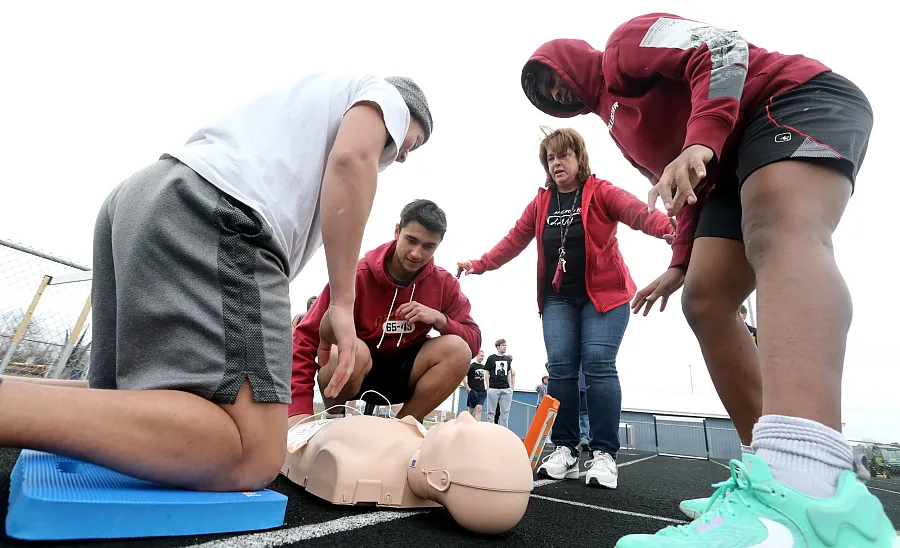

At the direction of Phillip Burton, a paramedic with Columbus Regional Health, students receive a lesson on using an automated external defibrillator, as well as CPR best practice, during a cardiac screening clinic at Columbus East High School in Columbus, Indiana. Feb. 24,

2023 MYKAL MCELDOWNEY/INDYSTAR

“When you see a collapse, 90% of people that don’t have CPR certification will not assist somebody because they’re afraid they’ll do it wrong,” Matt Mangine Sr. said. “That’s a fallacy… You don’t need a certification to render life support.”

But there are certain individuals who should be certified. Thirty-three states require CPR, AED and first-aid certification for high school coaches. This includes Kentucky, though enforcement of that certification has been spotty.

Mangine and his wife, Kim, set up a foundation in honor of their son, Matthew Mangine Jr., who died after he collapsed during a Northern Kentucky soccer practice in June 2020. Coaches did not administer CPR.

The Matthew Mangine Jr. “One Shot” Foundation does Take 10 Training: a 10-minute training that teaches you how to deliver chest compressions and how to deliver a shock with an automated external defibrillator or AED.

Following Hamlin’s collapse, the American Heart Association also launched the #3forHeart CPR Challenge, which includes a 60-second video on how to provide CPR.

Sideline AEDs

At least 20 states require AEDs in schools. Others recommend them, and still more are reviewing proposed legislation in the wake of Hamlin’s collapse.

But often, like in Kentucky, those AEDs aren’t for sidelines.

New Prairie High School educator Tonya Aerts, second from right, helps instruct track team members Camden Ziglar, left, Miguel Mendez, center, and Isaiah King on March 2, 2023, during a “sudden cardiac arrest” drill on the track. The girls' and boys' track teams at the Indiana high school underwent a drill where they performed CPR and practiced using an automatic external defibrillator (AED).

GREG SWIERCZ, SOUTH BEND TRIBUNE

“When we’re working with a superintendent, they think they have AEDs because there’s one next to the principal’s office or in the nurse’s office, but that doesn’t help us at all during the sports venues when all of the doors are locked,” Casa said.

That’s where an emergency response plan for sudden cardiac arrest can come into play. This plan is often part of a venue-specific EAP, that says exactly how to respond when the injury is sudden cardiac related.

Tonya Aerts, a teacher in New Prairie, Indiana, helped create the plan for her school after baseball player Mark Mayfield collapsed and died of sudden cardiac arrest in 2017. His death came four years after and 11 miles from where La Porte, Indiana, football player Jake West died of an undetected heart condition.

Aerts leads seasonal sudden cardiac arrest drills to practice the plan.

"We drill for all the other emergency situations to keep our students and staff members safe in a serious situation," she said. "Sudden cardiac arrest is something we can respond to, and we should respond to it. ...That level of preparedness can save a life."

Automated external defibrillator

- Open lid on AED

- Expose patient's chest and apply electrode sticky pads as shown on device

- AED analyzes cardiac rhythm

- If the AED device says shock is needed, push the "shock" button. (New AEDs may not require you to push a button to shock, they are fully automated.)

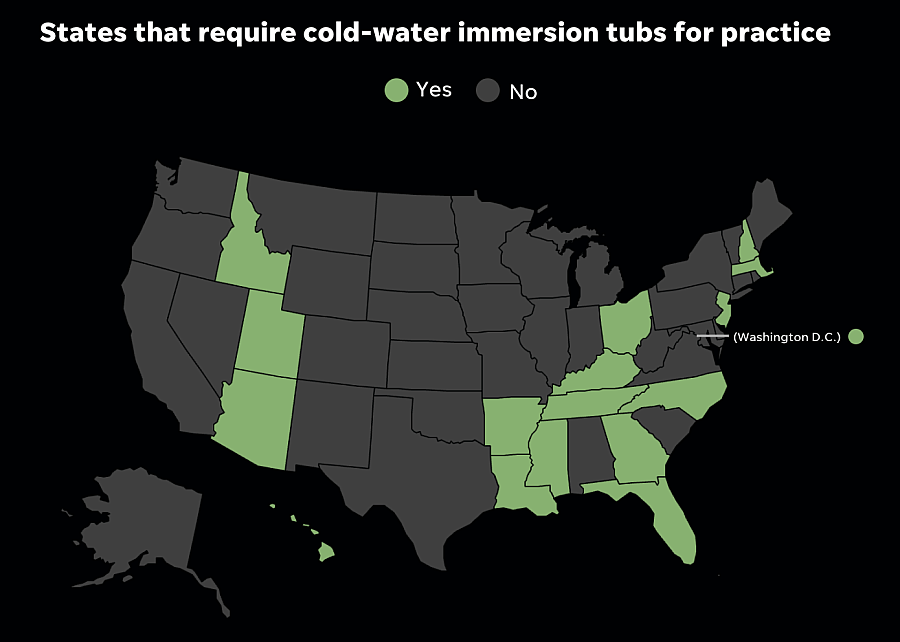

Cold tubs

The key to an overheating athlete is to cool them as quickly as possible, and the best way to do that is with cold water immersion.

That means having a cold tub (a plastic container big enough to submerge an athlete's core in the water) and access to ice and water ― such as from a nearby concession stand.

Cold tubs are very common at the college level, but not nearly as much on high-school sidelines. In Georgia, based on Cooper's data, a cold tub is required to be on sidelines when the WBGT is higher than 86 degrees.

Based on state laws and/or state athletic association requirements

SOURCE Korey Stringer Institute

The University of Cincinnati sets up 11 cold tubs during warm-weather practices. UC athletic trainer Aaron Himmler said every year for the last decade, he has placed four to five players in a cold tub who could have died had they “not gotten immediate care.”

The gold standard of care for transferring an athlete once they have suffered an exertional heat stroke is to cool first and transport second.

“I call it the magic elixir," Casa said. "That cold water immersion takes something that could kill you in a few hours or a couple of days and basically causes you to be fine within a day or two, all just from getting your temperature down rapidly.”