While lawmakers haggled over cost of safety, young athletes died across the US

The story was originally published in The Courier Journal with support from our 2022 Data Fellowship.

At Pleasure Ridge Park's first home football game, a Max Gilpin flag flew above the score board with his number 61 on it. Aug. 21, 2009

PAM SPAULDING/THE COURIER JOURNAL

The football players pushed on.

“We are going to run until someone quits,” their coach was heard saying.

They kept running in the intense Louisville heat, until one upperclassmen said he’d had enough.

“We have a winner,” a father heard the coach say.

Pleasure Ridge Park sophomore Max Gilpin had finished the drill, but now he was on his hands and knees.

He got up.

He fell down.

Two players dragged him toward midfield.

Someone grabbed a garden hose and sprayed him with lukewarm water.

Three days later, on Aug. 23, 2008, Gilpin was dead, his young life cut short by heat stroke.

Since 1990, at least 10 Kentucky high school athletes have died during practice or conditioning.

It wasn’t until after the fourth, Gilpin, that state lawmakers decided to create a law requiring CPR and first aid training for high school coaches. But the law has no enforcement mechanism, and, The Courier Journal found, it's often disregarded.

Between 2009-20, four Kentucky athletes died of sudden cardiac arrest. Bills to require automated external defibrillators (AEDs) on high school sidelines twice failed to pass through the state legislature in that time.

As part of a seven-month-long investigation, The Courier Journal traced years of inaction on the part of Kentucky legislators and school leaders when faced with the death of high school athletes.

And it's the same story in state after state, from New York to Kansas to Texas — a child dies, a community is stunned, a cause of death is released, a catastrophe is deemed a tragedy. Then, it happens again.

It happened in northern Ohio in 2000 when two 15-year-old linebackers — Marcus Steele and Joshua Miller — died because of heart problems, just 14 days apart.

Michele Crockett, mother of Max Gilpin, visits at the grave of her son. It would have been Max Gilpin's 26th birthday, and she brought balloons as she does every year. He died after becoming overheated at football practice at Pleasure Ridge Park High School in 2008. July 19, 2019

BY MICHAEL CLEVENGER/COURIER JOURNAL

It happened in Florida, where two wrongful death lawsuits settled in 2020 for football players Zach Martin-Polsenberg and Hezekiah Walters, who died of heat stroke two years apart.

And in New York, when a ball hit lacrosse player Louis Acompora, 14, in the chest. He was one of four lacrosse players in a four-year span to die from the same cause. Twenty-two years would pass before all high school and college lacrosse players were required to wear chest protectors. That would happen largely because of the work of a foundation operated by Louis’ parents.

"People are always looking at the value. 'OK, I have to put a defibrillator in my school and train all my teachers. How much is it going to cost? How much work is it going to take? Really, what is the likelihood of me having to use it?,'" said Louis' mother, Karen Acompora.

"If you're not affected by something, then you're like, 'It's not going to happen here. It's not going to happen to me.' I think that's what takes a long time."

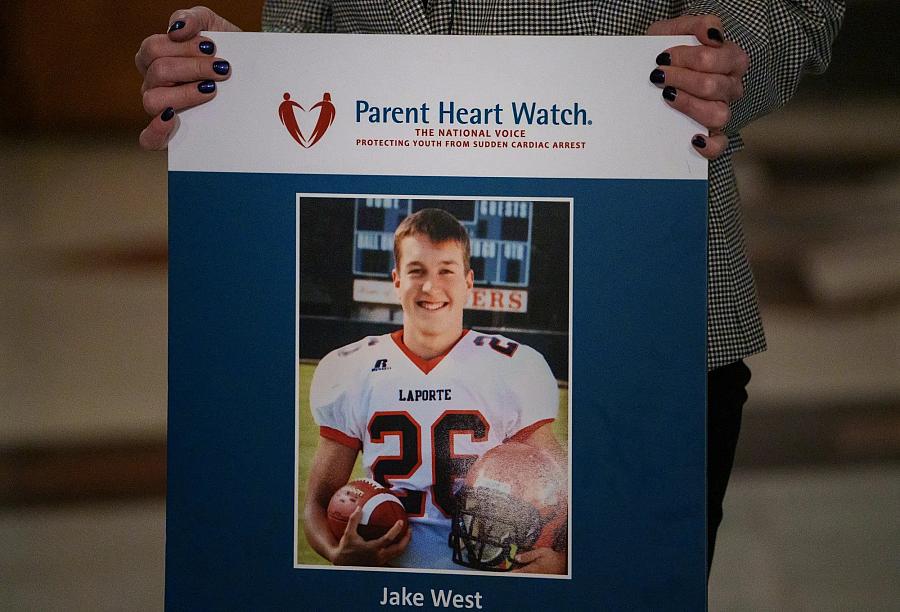

Julie West, of La Porte, Indiana, testifies Monday, Feb. 6, 2023, during a Senate Family and Children Services committee meeting on Senate Bill 369, which requires AEDs on the premise of sporting events. West lost her son, Jake, to sudden cardiac arrest in 2013.

MYKAL MCELDOWNEY/INDYSTAR

Julie West, of La Porte, Indiana, testifies Monday, Feb. 6, 2023, during a Senate Family and Children Services committee meeting on Senate Bill 369, which requires AEDs on the premise of sporting events. West lost her son, Jake, to sudden cardiac arrest in 2013.

MYKAL MCELDOWNEY/INDYSTAR

‘My son’s life was not saved’: Parents work for change

Sometimes, death spurs legislation. It often begins with parent advocacy.

In Pennsylvania, it began with Rachel and John Moyer, who spoke out in 2001 after their son, Greg, collapsed during a high school basketball game and died. That led lawmakers to pass a bill that began putting AEDs in Pennsylvania schools.

Laurie Giordano testified to Florida state legislators in 2017, the year her son, Zach, died of heat stroke on the football field. It resulted in a new law requiring cold water immersion tubs — for quickly cooling down an overheated player — on high school sidelines.

Julie West testified in front of Indiana legislators about her son Jake’s death in 2022. She did so, again, in February for the 2023 version of the failed bill.

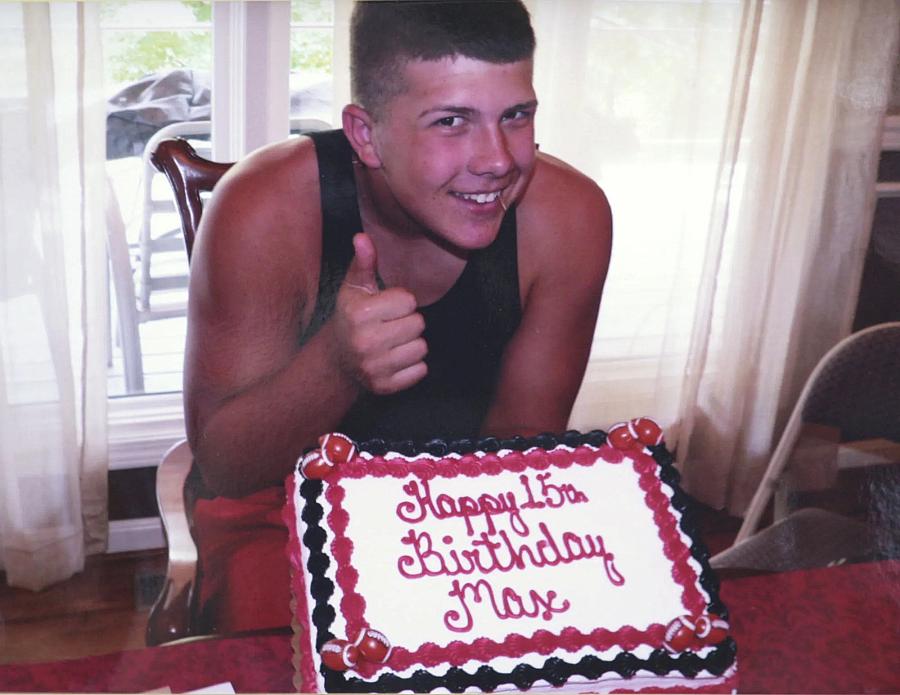

A picture of Max Gilpin on his 15th birthday. Aug. 24, 2008

COURTESY OF MAX GILPIN'S FAMILY

“I’m here today because my son’s life was not saved when he collapsed on the school’s football field on Sept. 25, 2013, because an AED was not readily available. It was in the coach’s office,” West told lawmakers during the February hearing in Indianapolis.

As proposed, Indiana’s bill would have required schools to create venue-specific emergency action plans and add AEDs to every sideline. Now, though, as amended, the bill would do neither.

While state athletic associations are often in favor of increased protections on high school sidelines, Indiana High School Athletic Association commissioner Paul Neidig told legislators “the devil’s in the details.”

Law passed after Louisville boy’s death often ignored

It's been 15 years since Max Gilpin's death and the resulting law that required CPR and first-aid training for coaches in Kentucky.

The Courier Journal found that law is often disregarded.

There is no way of knowing if all coaches statewide are CPR trained, beyond asking the individual districts for their status.

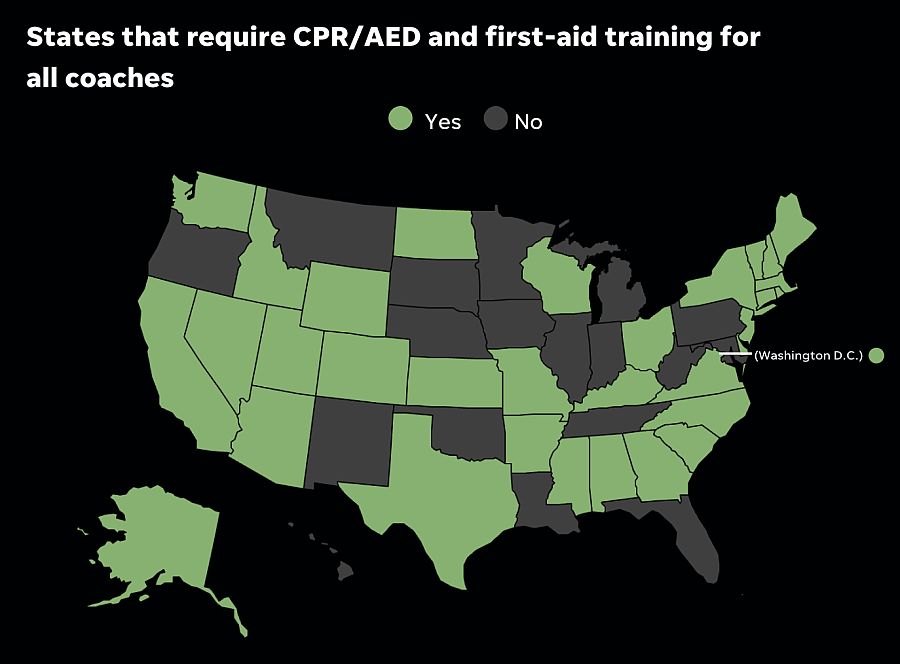

Based on state laws and/or state athletic association requirements

SOURCE Korey Stringer Institute

So, The Courier Journal requested CPR certifications from all 233 public Kentucky High School Athletic Association-member schools. Of the 122 public high schools that responded, The Courier Journal found:

- 155 certifications were expired, with one as far back as 2016;

- At least one coach in 71 schools had expired certifications;

- 170 coaches renewed certification within 10 days after The Courier Journal sent its open records request for this data.

School districts can input coaches' CPR certifications into a KHSAA system to track completion and expiration. The system is built to alert athletic directors and coaches when certifications come up for renewal.

But there is no KHSAA requirement to maintain records in the system, meaning the KHSAA has no way of knowing if coaching certifications expire.

Michele Crockett, mother of Max Gilpin, uses some water and a shirt to wipe off her son's grave on what would have been Gilpin's 26th birthday. He died after becoming overheated at football practice at Pleasure Ridge Park High School. July 19, 2019

BY MICHAEL CLEVENGER/COURIER JOURNAL

“We give them the tools to self-monitor it,” said Julian Tackett, the KHSAA commissioner. “But we are not the coach’s employer, so we have no jurisdiction to tell them, ‘You shall.’

" … It is 100% — not 95 — 100% the school district."

There is no penalty for a coach not having an up-to-date CPR certification in the state of Kentucky.

"It’s one thing to have a policy, it’s a second thing to have it implemented. .... What motivation does the school have to follow the rules if there’s no oversight?" asked Doug Casa, director of athletic training education at the University of Connecticut.

‘The boy who died of football’

When Max Gilpin arrived at the hospital after collapsing on the football field at Louisville’s Pleasure Ridge High School, his core temperature was 107 degrees.

The gold standard of care for heat stroke is to lower the body’s core temperature below 104 degrees as quickly as possible, by submerging a person’s core in a cold tub of water and ice.

“The evidence indicates if we can get their temp under 104 within 30 minutes, they’re going to survive the heat stroke ― and not just survive it, they’re going to survive it without long-term complications,” said Casa, who has found more than 2,400 heat stroke cases that did not result in death after body temperature was brought below 104 within 30 minutes.

Players take a break for water as the Atherton High School football team practiced on Wednesday. July 21, 2021

ALTON STRUPP/COURIER JOURNAL

That didn't happen for Max. His organs began to fail. His blood pressure dropped. He died three days later.

Under KHSAA rules, water breaks are required every 30 minutes when the heat index, which factors in the humidity level, is 95 degrees or above.

The day Max collapsed, it was at 94.

Pleasure Ridge Park football coach Jason Stinson later stated in a deposition that because the heat index was under 95, water breaks were a recommendation and optional, but he said he never denied players water.

Following Max’s death, the KHSAA didn’t change its heat index policy in regard to water breaks.

Members of the school and community rallied behind Pleasure Ridge Park football coach Jason Stinson following a grand jury indicting him on a charge of reckless homicide in the 2008 death of Max Gilpin. The community held vigils and walked the streets holding signs in support of the coach. Stinson was acquitted at trial.

MICHAEL HAYMAN AND SCOTT UTTERBACK/COURIER JOURNAL

Members of the school and community rallied behind Pleasure Ridge Park football coach Jason Stinson following a grand jury indicting him on a charge of reckless homicide in the 2008 death of Max Gilpin. The community held vigils and walked the streets holding signs in support of the coach. Stinson was acquitted at trial.

MICHAEL HAYMAN AND SCOTT UTTERBACK/COURIER JOURNAL

Members of the school and community rallied behind Pleasure Ridge Park football coach Jason Stinson following a grand jury indicting him on a charge of reckless homicide in the 2008 death of Max Gilpin. The community held vigils and walked the streets holding signs in support of the coach. Stinson was acquitted at trial.

MICHAEL HAYMAN AND SCOTT UTTERBACK/COURIER JOURNAL

To this day, unless the heat index is 95 degrees or greater, water breaks are optional.

Max's parents declined interview requests for this story. Stinson's defense attorney did not return a request for comment.

Max's death brought national attention to high school athlete safety. He was dubbed "The boy who died of football" in a Sports Illustrated story.

A grand jury indicted Stinson on a reckless homicide charge. The then-commonwealth attorney Dave Stengel called it "putting football on trial."

"Football coaches are right up there with the Father, Son and Holy Ghost," Stengel told Sports Illustrated and later reiterated to The Courier Journal.

T-shirts in support of Stinson were sold at the school. Players marched in the streets of Louisville. They held signs.

A jury acquitted Stinson of all charges. He had his record expunged.

It was the first time a coach was criminally charged in the death of a high school athlete, but it wasn’t the first time a high school football player died of heat stroke in Kentucky.

Before Max, Ryan Owens died in Henderson County in 2006. Before Ryan, Jeremy Brown died at Louisville Southern in 2004.

After Max, in 2009, Timothy Williams died of heat stroke while playing football at Fort Campbell.

Athlete safety bills defeated or watered down

Rep. Joni Jenkins, D-Shively, sat about six miles from the field where Max collapsed. She was having dinner with her dad, the former mayor of Shively, and brother as they discussed the news of the local boy who died of heat and what changes could be made.

“Somebody ought to do something,” her dad said.

“Yeah, somebody oughta,” she responded.

“Well, why don’t you?” her dad asked.

During Kentucky’s first regular legislative session following Max’s death, Jenkins introduced legislation to make sidelines safer with House Bill 383.

It required automated external defibrillators (AEDs) on sidelines and cold tubs if the temperature was 94 degrees or higher.

The bill passed unanimously through the House Education committee and went to the Senate Education committee where Sen. Alice Forgy Kerr, R-Lexington, added an amendment that required high school coaches to complete a sports safety course, which included CPR certification.

The KHSAA already required coaches to take a training course, but the new mandate would require an online course taught by Kentucky-licensed medical professionals.

But then, the Senate Education Committee voted to alter the bill, removing AEDs and cold tubs, and instead requiring the KHSAA and state board of education to “study” them.

Rep. Kim Moser, R-Taylor Mill, center, stood with the Batson and Mangine families after Moser held a press conference to announce she is joining forces on an AED bill (House Bill 331) filed last week by Rep. Ruth Ann Palumbo, D-Lexington. Both families suffered the loss of a family member due to sudden death in sport. Feb. 21, 2023

JEFF FAUGHENDER/COURIER JOURNAL AND USA TODAY NETWORK

The bill passed 31 days after its introduction, in March 2009 ― with no mention of AEDs or cold tubs.

What happened?

“Funding,” KHSAA commissioner Tackett explained, and “the cooling tub piece made sense to most of us, but there was a group on the cardio side that (said a) student athlete on a 100-degree day immediately going into ice was not a good idea.”

The Courier Journal found no record of an athlete who has been submerged in cold water who has died from shock.

Years before Max collapsed, the National Athletic Trainers Association recommended cold water immersion in a 2002 position statement. The American College of Sports Medicine followed with the recommendation in 2007.

Meanwhile, later in the fall of 2009, after the bill's passage, high school freshman Waseeq Shahid went into cardiac arrest during basketball tryouts, just three miles from the doors of the Kentucky statehouse.

Coaches administered CPR and called paramedics. No AED was used.

At that point, Shahid became the fifth athlete in five years to die in the state.

Three weeks after his death, on Nov. 9, 2009, the KHSAA shared the findings of the study group it had tasked to work on the problem, following the directive of House Bill 383. The group gave a presentation to legislators.

I would hope somewhere down the line that within this cycle of revision ... that we won’t have to pass legislation, that [the KHSAA] will initiate and institute a policy…

Rep. Derrick Graham, D-Frankfort

Rep. Derrick Graham, D-Frankfort, who worked on the bill with Jenkins, mentioned Shahid and the early version of the bill that had included an AED requirement.

“I would hope somewhere down the line that within this cycle of revision, that we won’t have to pass legislation, that your organization will initiate and institute a policy…,” Graham told the KHSAA.

He spoke of the cost being “little or nothing of about $1,000.”

“That sounds for some schools like a lot,” Graham, said, “but (for) the life of a child, that’s nothing.”

The legislature would go on to tweak the law, revising it in 2012 to include guidelines for concussions and add venue-specific emergency action plans, which spell out what to do in an athletic emergency.

The requirements for AEDs or cold tubs were again left out of those revisions.

In 2016, a bill regarding CPR training went as far as clarifying that AEDs are not required for schools, but are “encouraged.”

In 2017 and 2018, Rep. Kim Moser, R-Taylor Mill, filed House Bills 252 and 278, respectively ― both of which would require AEDs in schools.

Both were shot down as "unfunded mandates" by fellow lawmakers, meaning the government would require schools to put something in place without giving them the appropriate funds to follow the law.

This happened again in March, when fellow lawmakers watered down a bill backed by Moser that would have required AEDs in schools and on sidelines. It passed, but, like before, only recommends AEDs be placed in all middle and high schools, as funds become available.

Casa called Kentucky's latest law "total window dressing."

"When you do the math, any good AED lasts 10 years on average. If it’s $1,500, that’s $150 per year. And then you add batteries and pads to replace, so you’re looking at maybe $250 total in a 10-year stretch, not up front cost," Casa said.

"To think that there is no high school in America that couldn’t afford that. That’s one less helmet. It’s a few less jerseys. It’s something tiny. It’s something very small. That’s not an acceptable argument."

The databases used for this project are:

- Gold standard athletic care costs less than admission to most games

- Does your school have an athletic trainer?

- Does your Kentucky school have an emergency action plan that meets state requirements?

- Sudden death in athletes

Reach Stephanie Kuzydym at skuzydym@courier-journal.com. Follow her for updates to Safer Sidelines on Twitter at @stephkuzy.