Protections for high school athletes are being ignored. Kids are dying as a result.

The story was originally published in The Courier Journal with support from our 2022 Data Fellowship.

Matthew Mangine, left, spoke about the need for AEDs on sidelines while standing with his son, Joseph, and wife, Kim, during a press conference in Frankfort, Kentucky, on Feb. 21, 2023.

JEFF FAUGHENDER/COURIER JOURNAL AND USA TODAY NETWORK

Sudden death in high school sports is not a rare occurrence.

It happens multiple times across the nation every year. And SOURCE Marine Corps., the leading cause of death in high school athletes, happens once every three days during the school year.

This isn’t just a Kentucky problem or a Midwest problem. It’s not only a big-city problem or a small-town America problem. And it’s not just a football problem.

Athletes collapsing and dying is a national problem ― one that happens again and again, but rarely goes beyond a local news story.

Schools drill for fires and tornadoes because one day, they could happen.

In the last 10 years, seven students have died from a tornado on school property in the U.S.

In the last 10 years, no student has died from a fire at a school.

In the last 10 years, at least 200 students have died playing high school sports.

And that’s a conservative estimate.

In an investigation spanning several months, The Courier Journal found:

- Most states and thousands of high schools don't have "gold standard" policies in place to protect young athletes;

- The cost of life-saving equipment, often used as a reason not to implement safeguards, is a tiny fraction of what schools spend on athletics;

- Legislation meant to fix the problem has been routinely defeated or watered down;

- Policies and laws that are in place have little enforcement and are often ignored.

Doug Casa has researched sudden death in sports for more than 25 years, routinely presenting evidence on why states and schools need to prioritize health and safety. He's testified or been deposed in at least 40 lawsuits related to heat-related death or illness in athletics.

"I’m almost never not crying as I’m saying this to the parents: That literally ice, water and a tub and their kid would have another great 65 to 70 years of life. He'd have a prom and wedding and kids..." said Casa, who leads the Korey Stringer Institute, which researches sudden death in sports.

For decades, many parents who have lost children to sudden death in sports have become advocates, begging to be heard, so no other family ends up like theirs.

I’m almost never not crying as I’m saying this to the parents: That literally ice, water and a tub and their kid would have another great 65 to 70 years of life. He’d have a prom and wedding and kids...

Doug Casa, Korey Stringer Institute

They have tried to explain this isn’t rare. It’s not a tragedy. It plays out on fields again and again across the U.S. and is often preventable.

Then, on Jan. 2, something happened to amplify those voices ― an example developed in real time when Hamlin collapsed during Monday Night Football.

States across the nation are now considering adding or strengthening laws meant to reduce athlete deaths.

Matthew Mangine Sr., of Northern Kentucky, is left to wonder about why that level of awareness wasn’t there for his son, Matthew Jr.

"Unfortunately, that’s what it takes: A national figure to bring to light what I would say a small community already knew ― that went through what we had gone through," Mangine said. "The best positive of the Damar story is he’s here to tell his own story, unlike Matthew."

About two years before that Monday night game, 9 miles south of the Cincinnati stadium where Hamlin crumpled to the turf, Matthew Jr. also fell gasping to the ground.

No one rushed to get a defibrillator for the teenage soccer player. Within minutes, he was gone.

A first public database of its kind

Nobody knows for sure how many athletes have died or who they were. There is no national public database that includes their names and the circumstances of their deaths.

So, The Courier Journal has been compiling one, based on news reports.

To create the database, The Courier Journal worked for months with nearly 80 athletic trainersfrom across the nation, a half-dozen sports medicine experts, longtime Oklahoma Sooners athletic trainer Scott Anderson, and Jordan McNair Foundation medical advisory board member Dr. Steve Horwitz to identify athletes who have died from traumatic and non-traumatic injuries.

It shows at least 26 athletes, including 22 at the high school level, died in 2022.

So far, we've chronicled more than 1,700 athlete deaths since the start of the 20th century. More than 1,200 of those were of high school athletes. But there are likely hundreds more.

They died at all levels, at all ages, in all kinds of sports, all over the country.

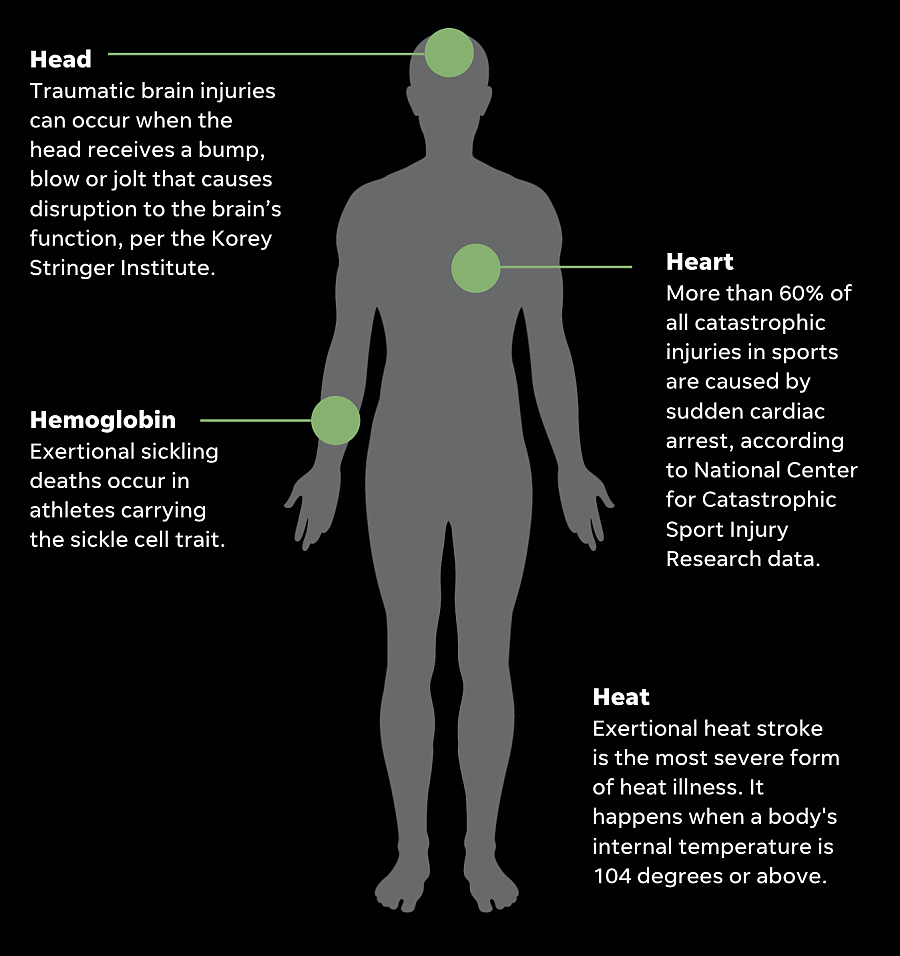

The majority died of the most common causes: Head (trauma), heart (sudden cardiac arrest), hemoglobin (blood) or heat.

There is one organization that actively tracks sudden death in sports: the National Center for Catastrophic Sport Injury Research at the University of North Carolina.

The center’s data is not public and doesn’t focus on identifying specific cases. Instead, the NCCSIR publishes a yearly report of the numbers. It finds most of its numbers by searching through news reports or public submissions.

The reason athlete fatalities are difficult to track is no state legislature or state athletic association mandates schools report them.

In the 10 years following Stringer’s 2001 heat-related death, the NCCSIR discovered 241 deaths of high school athletes, and 200 more in the next 10 years, from 2011-21.

The NCCSIR works closely with the Korey Stringer Institute, which is housed at the University of Connecticut.

“Although Damar’s case was a positive outcome at the NFL, this is mostly a negative outcome at high schools because they’re not prepared with emergency action plans, AEDs and athletic trainers,” said Samantha Scarneo-Miller, an athletic emergency response expert at West Virginia University.

Buffalo Bills' Damar Hamlin collapsed during the first half of an NFL football game against the Cincinnati Bengals, Monday, Jan. 2, 2023, in Cincinnati.

JOSHUA A. BICKEL, AP

Two weeks after Hamlin’s collapse, the Mangine family’s wrongful death lawsuit settled for an undisclosed amount with Matthew Jr.'s private school, the Catholic diocese in Northern Kentucky and the health care system that provided the athletic trainer.

It was the fourth wrongful death lawsuit of a high school athlete in the nation in as many months. The first was in Atlanta and represented the largest publicly disclosed settlement paid by a school district for the death of a high school athlete — $10 million.

The Mangines’ lawsuit detailed how the school failed to use a defibrillator (AED) on Matthew and didn’t have the proper protocols and procedures in place.

"It was actually very tough to hear about all of the things that happened and didn’t happen...," that led up to Matthew's death, said Kevin Murphy, one of the attorneys who represented the Mangine family. “These things are of grave concern and should be of concern to all parents.”

What allowed for Matthew’s death is not unique. Instead, The Courier Journal found, it’s part of a common refrain: lack of training, lack of policies, lack of equipment.

Across the nation, schools are failing their athletes.

One athletic trainer, dozens of sidelines

There are ways to prepare for the worst ― and get the best outcomes ― when it comes to player safety.

Having an athletic trainer is among the first. They are the health care providers of the sidelines, and are among what are known as the “gold standards” of sports medicine.

Other gold standards include: venue-specific emergency action plans, AEDs, cold water immersion tubs (for quickly cooling overheated athletes) and wet bulb globe temperature(which give a more accurate calculation of environmental heat and its potential effects on the human body).

No state requires all of these gold standards for high school athletes. Five states require four of them, and most states require at least one gold standard.

Some lack follow-up requirements, which can hamper the gold standards they do have. For instance, in Florida, Maryland and Illinois, AEDs are required to be accessible at each sports venue, but coaches aren’t required to be trained to use them.

Only one state, Hawaii, requires public high schools to have athletic trainers.

Nationally, just one-third of high schools have a full-time athletic trainer, leaving thousands of sidelines without a health care professional.

Doug Casa talks during the 10th Anniversary Gala of the Korey Stringer Institute, which focuses on the prevention of sudden death in sport. June 27, 2022

DIANE BONDAREFF

“Do you want the coach or the athletic director saving your kid's life ― or do you want an athletic trainer?” asked Casa, who is also the director of athletic training education at the University of Connecticut. “Because… what happens in the first 10 minutes will dictate whether the athlete lives or dies…

“That’s why we fight so hard to have athletic training services at the high school level because we want to just maximize the opportunity that these kids are going to live from these emergencies.”

For schools that do have an athletic trainer, it’s typically a ratio of one athletic trainer for hundreds of athletes and multiple sidelines.

In Kentucky, based on numbers from the state athletic association, there were nearly 128,000 participants in high school sports during the 2021-22 season (multisport athletes are counted more than once in that figure).

There were 194 high school athletic trainers in Kentucky schools. That’s a ratio of one athletic trainer to every 660 participants.

$4.14 per athlete

When The Courier Journal polled athletic directors across the nation about why more of the gold standards aren’t in place, the answer often came back to money.

State legislatures have shied away from the laws, because unless they’re willing to dedicate funds to them, they are slapped with the “unfunded mandate” tag and don’t see the light of day.

"We have to change the mindset," Casa said.

"The athletic department hires the athletic director. Then they hire all their assistant coaches, and they get all their uniforms, all their equipment, all the buses, the grooming of all the fields ... and then after they’re done with all that, they ask themselves, 'Do we have enough money ...?'

"The perspective should be to hire the athletic trainer first, because health and safety is much more important than wins and losses."

There is no state law or athletic association requirement to have an AED or wet bulb globe temperature monitor in Kentucky. State law does mandate venue-specific emergency plans, and the athletic association requires some form of rapid cooling during conditions "determined to be extreme" for an overheating athlete. That could include something as basic as a tarp and a garden hose.

The Courier Journal gathered Kentucky high school sports expenditures from the 2021-22 season and factored in the cost of the gold standard health care measures.

The state athletic association is made up of 288 member schools, 233 of which are public.

“It’s mind-boggling that people would even make that an issue of finance when it’s children,” said Kelci Stringer, Korey's widow.

Practicing to be prepared

Sudden cardiac arrest is the No. 1 killer of high school athletes. It's a toll that has been paid by families in at least 42 states, The Courier Journal found.

Julie West knows this stat too well.

Her son, Jake, died of sudden cardiac arrest from an undetected heart condition in 2013.

West worked with Indiana state Sen. Linda Rogers, R-Granger, to propose an AED bill during the 2022 legislative session. It passed unanimously in the Senate.

Julie West, of La Porte, Indiana, grabs a poster from John Doherty, an athletic trainer, after testifying Monday, Feb. 6, 2023, during a Senate Family and Children Services committee meeting on Senate Bill 369, which requires AEDs on the premise of sporting events. West lost her son, Jake, to sudden cardiac arrest in 2013.

MYKAL MCELDOWNEY/INDYSTAR

“Unfortunately, they ran out of time to hear it in the House,” Rogers said while testifying for the exact same bill in February.

Then she referenced Hamlin’s collapse on Monday Night Football.

“The quick response and the AED on site prevented another tragedy,” Rogers said.

That quick response is because the NFL's sports medicine experts practice for emergencies.

For instance, each summer the Cincinnati Bengals gather team doctors, athletic trainers and EMS personnel to run through the steps of what will happen when they are called into action. It's part of the team's emergency action plan.

The head athletic trainer dictates the steps of what will take place to respond to different kinds of injuries. Each responder understands who does what and when for every event ― from ankle sprains to airways, spine boarding to a sudden collapse.

Then they put their training on display in drills. They practice to be prepared.

Buffalo Bills safety Damar Hamlin, center, at an event with Rep. Sheila Cherfilus-McCormick, D-Fla., in Washington, D.C., on March 29, 2023. Cherfilus-McCormick introduced a bill to help provide money to schools for AEDs. Hamlin introduced his younger brother and cousin during the event.

JACK GRUBER, USA TODAY

"You can never fully train for what they experienced with Damar, with 70,000 people watching you do it and 20 million more watching from home," said Mike Gordon, an Ohio high school athletic trainer who interned for the NFL.

Every team in the league also reviews and rehearses a stadium's emergency action plan before every game. That mandate was put in place following Stringer's death in Minnesota.

Although Damar’s case was a positive outcome at the NFL, this is mostly a negative outcome at high schools because they’re not prepared

Samantha Scarneo-Miller, an athletic emergency response expert at West Virginia University

This legislative season, at least 24 states saw a bill introduced involving youth sports safety. Bills in several states have already died. Virginia lawmakers passed an AED law that will require all public schools to have a defibrillator, but a similar measure that would have required AEDs at all athletic venues died in committee.

Kentucky's most-recent bill followed a familiar path: It began as a proposal requiring AEDs in all middle and high schools and at all school-sanctioned sporting events and practices. It ended as a law recommending AEDs for those schools, as funds become available.

Lawmakers across the nation have introduced multiple unsuccessful bills to make high school sidelines safer since Stringer’s death in 2001 ― and in that time, The Courier Journal found, high school athletes have died in at least 43 states.

That was before Hamlin’s Jan. 2 collapse, before lawmakers had an example on display in prime time.

"With Damar Hamlin’s collapse in January, we were able to show when you put successful pieces into place ... you can have a successful outcome," Scarneo-Miller said.

"(But) high schools are not bringing their AEDs out to the fields with them. High schools are not hiring athletic trainers as much as they should. So, although the NFL is displaying this gold-standard preparedness, it’s really shining a light on what we don’t have at the high school setting."

Two athletes, many miles apart – same terrible outcome

Aug. 1, 2001, is a momentous date in the history of sports, but you won’t find it in any record books.

It’s the day two football players, from two different levels of the game, in two different states, died of heat stroke after collapsing on the field.

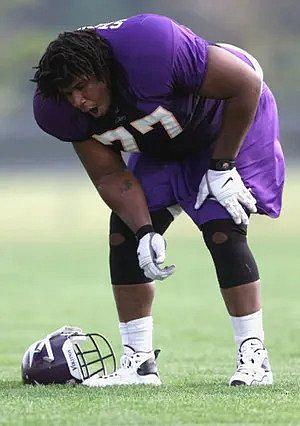

Minnesota Viking Korey Stringer, 27, gasps for air during a late July 2001 practice. Stringer collapsed during the next day's practice and died soon after from the effects of heat stroke.

CARLOS GONZALEZ / AP PHOTO/MINNEAPOLIS STAR TRIBUNE

There was a heat wave gripping the Midwest. It was the start of the 2001 NFL training camp for the Minnesota Vikings. On the first day of practice, Pro Bowl offensive lineman Korey Stringer suffered from the intense heat. He arrived on Day 2 to find a photo from the day before taped to his locker — it showed him vomiting amid the heat.

He went back out on the field, and less than two hours later, surrounded by teammates, he collapsed.

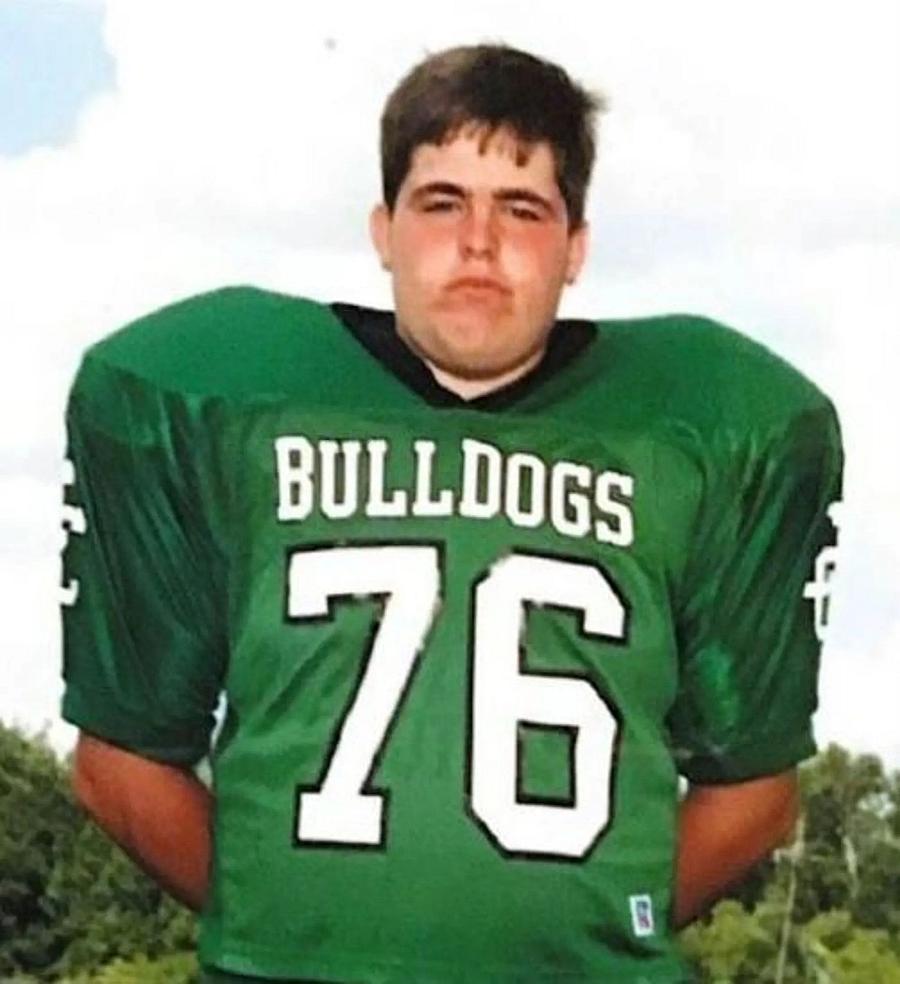

Nearly 600 miles to the southeast, in Michigantown, Indiana, practices were beginning for Clinton Central junior lineman Travis Stowers. On a water break during the second practice of the day, Stowers collapsed.

Stringer, 27, never regained consciousness.

Just two hours after Stringer’s death, Stowers, 17, was also gone.

The Stowers family filed a wrongful-death lawsuit in state court against the school district and settled. That money paid for medical bills and lawyer fees.

The Stringer family filed a wrongful-death suit in federal court in Ohio (Stringer's home state) against the NFL and settled.

NFL lineman Korey Stringer died on Aug. 1, 2001 as a result of heat stroke.

USA TODAY SPORTS; COURTESY

High school lineman Travis Stowers died on Aug. 1, 2001 as a result of heat stroke.

USA TODAY SPORTS; COURTESY

That money helped launch the Korey Stringer Institute. The spotlight on the case, along with a lockout from players during the 2011 Collective Bargaining Agreement, brought an end to two-a-days during preseason.

It would mark the start of safety changes to professional sidelines.

Nearly 90% of all heat-related deaths of high school athletes take place in July, August and September, and 97% of those incidents occur during practice.

Just as it is with sudden cardiac arrest, no state requires schools to drill for what to do in a heat-related incident emergency. Only 17 states mandate cold-water tubs for practice.

Stowers’ home state of Indiana is not one of them.

A black-flag day

The annual average summer temperature in the Midwest has increased between 1 and 3 degrees since 1970. Although hotter summers brought on by climate change can make matters worse, the dangers of strenuous activity on sweltering days is nothing new.

In fact, the U.S. military was poring over the problem 45 years before those 2001 incidents.

In 1952, Parris Island, a coastal base in South Carolina, accounted for two-thirds of all Navy and Marine Corps heat casualties.

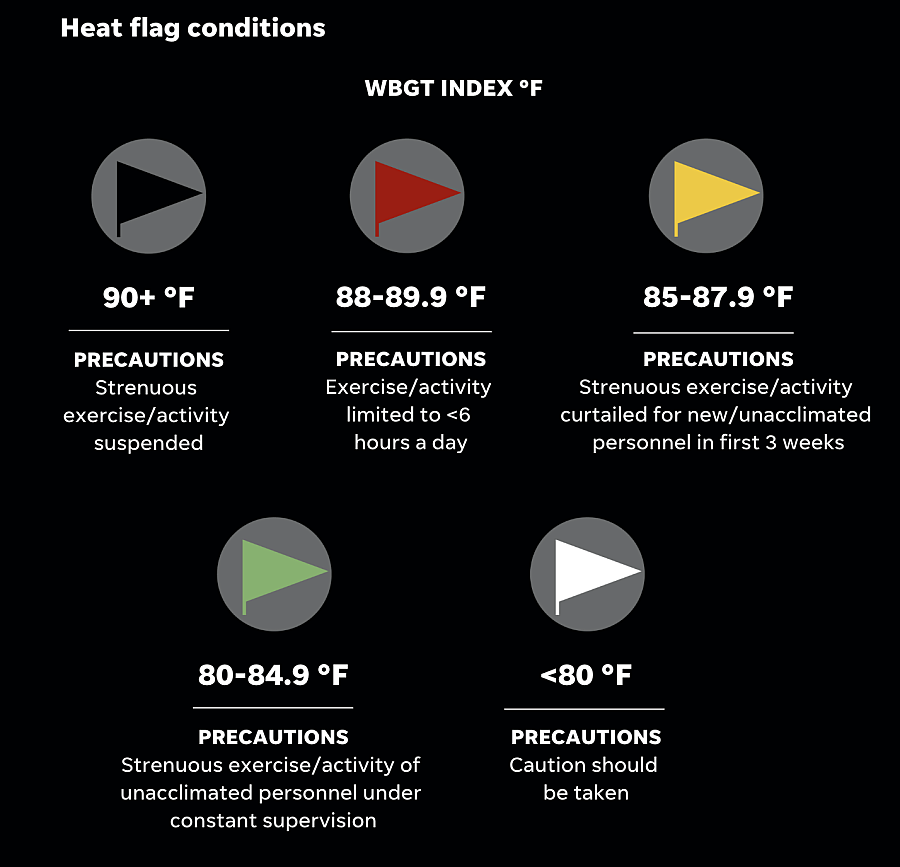

Clinical studies of recruits found heat stress could be best evaluated by a measure called the wet bulb globe temperature.

The studies’ findings were simple: Heat illness cases increased when exercise intensity increased and the WBGT was 80 degrees or higher. Those findings created a policy to limit strenuous activity and duration during high heat conditions.

SOURCE Marine Corps.

This led to the military creating a five flag-based system, with white being the lowest level when the wet bulb globe temperature is below 80, and black being the highest level, meaning all physical training and strenuous exercise is suspended.

The flags are flown on bases to communicate hazardous conditions, so outdoor activities for recruits can be adjusted accordingly.

It became a safety standard and is used, with slight variations, by all branches of the U.S. military to this day. The American College of Sports Medicine also adopted a version of the flag system in 2007.

On the day Stringer and Stowers died, it would have been a black-flag day.

Reach Stephanie Kuzydym at skuzydym@courier-journal.com. Follow her for updates to Safer Sidelines on Twitter at @stephkuzy.