This San Diego child care gives kids ‘a higher chance of thriving.’ But California doesn’t pay providers enough to cover their costs

This story was originally published in The San Diego Union-Tribune with support from the 2022 National Fellowship.

Adriel, 3, eats some berries with the other children whom child care provider Miren Algorri, standing, serves at her home.

Eduardo Contreras / The San Diego Union-Tribune

Miren Algorri wakes at 4 a.m. and sleeps by 11 p.m. — when she can.

On weekdays and some weekends and holidays, Algorri takes care of and teaches as many as 14 children — some as young as babies, others as old as 9 — in her Chula Vista house.

The first is dropped off at 6:30 a.m. when his mom goes to work as a cook. The last, whose mom works late at a pharmacy, isn’t picked up until nearly 8 p.m.

In between, the 48-year-old Algorri and her two assistant teachers make the children breakfast, lunch and dinner with foods like mangoes, oatmeal, fish, broccoli and milk. They change the babies’ diapers. Algorri picks the older kids up from school.

Sitting cross-legged on the floor, the teachers read books, play games, practice social skills. They flood Algorri’s sunlit, toy-filled living room with a stream of language that slips seamlessly between English and Spanish as the children squeal, smile and exclaim in wonder.

“Negotiating, conflict resolution, self-regulation ... these are skills they’re going to need for the rest of their lives,” Algorri said

Adriel, 3, looks at a book about dinosaurs with Miren Algorri on Thursday, Nov. 17, 2022.(Eduardo Contreras / The San Diego Union-Tribune)

For all this work, Algorri can’t afford to pay herself a salary, after working in child care for 31 years. She relies on her husband’s military salary and benefits to get by.

Algorri, who opened her business in 1997, serves only low-income families who get state-subsidized child care. That means she relies on state subsidies to fund her business.

But those subsidies often don’t even cover her expenses.

Much of why it’s so hard for many parents to find child care can be traced to one longstanding problem: Child care is undervalued in America, and providers aren’t paid enough — neither through private tuition paid by parents nor public subsidies paid by the government.

In California, the providers who teach and care for the state’s neediest children are paid through a patchwork of public programs and at rates based not on their real costs, but on years-old prices in what economists agree is a failed market.

The consequences of this underfunding fall onto families with young children, who on average must spend 13 percent of their family income on child care, according to a 2021 U.S. Treasury report. In 2021, infant care at a child care center in California cost most families on average $19,500 a year, while preschool cost $14,400 a year.

But much of the burden is also shouldered by child care workers, the roughly 138,000 teachers, center directors and small-business owners who prop up California’s strained child care industry — virtually all of them women, mostly women of color, many of them immigrants.

Incomes for small family child care providers in California typically run as low as $16,200 to $30,000 a year, according to 2020 data from the UC Berkeley Center for the Study of Child Care Employment. Teachers at child care centers make slightly more: The median pay for a teacher is $39,500, while a center director makes $54,100.

One-third of family child care providers, half of child care center directors and two-thirds of child care center teachers worry they don’t have enough to pay their bills, the UC Berkeley center found. About a third of family child care providers and child care center teachers require some public assistance, and about a third experience food insecurity.

Employment benefits are often even more scarce for family child care providers like Algorri, who run small businesses out of their homes.

These providers serve more than a quarter of all children attending licensed child care programs in California — and because they are more likely than child care centers to offer nontraditional hours, they are sometimes the only option for parents who don’t have the luxury of a 9-to-5 work schedule.

Less than half of family child care providers reported having paid time off as part of their agreements with families. Only a fifth have any retirement savings, and 13 percent lack health insurance. Two-thirds of family providers work more than 40 hours a week.

The under-compensation of child care — an issue happening nationwide, not just in California — in turn limits the supply of child care.

One-year-old Ares shares a laugh with assistant teacher Lucy Arevalo at Miren Algorri’s family child care.(Eduardo Contreras / The San Diego Union-Tribune)

“Because we have such low wages in the field, people are not flocking to it to fill the spots that we have,” said Elizabeth Pufall Jones of the UC Berkeley Center for the Study of Child Care Employment. “We just do not have enough child care in this country for the number of children that are in need. That all has to do with the payment of the actual workers. If we paid them decently, then they’d be there.”

That has left California with fewer than half as many child care spaces available as children who need them. For the roughly 1.7 million California children under 6 who had working parents in 2021, there were only 560,100 spaces in child care centers and fewer than 267,900 spaces in family child care homes, which serve children from a mix of ages together, according to the California Resource and Referral Network and census estimates.

The shortage of child care workers also prevents California from serving more children in subsidized child care, the state’s main source of support for families who can’t afford care.

In 2020, subsidized child care served only 6 percent of the state’s children under age 4, according to data from the American Institutes for Research Early Learning Needs Assessment Tool. Nearly 600,000 children who qualified did not receive it.

Even if the state agrees to pay for more subsidized child care spaces — as it has the past two years — that doesn’t guarantee they will go to use if there aren’t enough providers who can serve more children.

“There’s never been enough child care spaces, ever. Subsidized or not,” said Keisha Nzewi, director of public policy for the California Child Care Resource and Referral Network, a nonprofit that represents child care referral agencies across the state. “Child care is an extremely low-paid field. Child care workers, child care providers don’t have health care, retirement, vacation ... all the things that people who work elsewhere have, they don’t have. That’s typically why there’s never enough care.”

A lack of adequate revenue, whether from parents or the state, and difficult working conditions have paved the way for hundreds of child care providers to shut their doors in recent years — a phenomenon that was exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic. Many providers who have managed to stay afloat say they can’t serve more kids because they can’t find or afford to hire enough staff.

“You can go to In-N-Out or Starbucks and make more with less work, and even get benefits,” said Shawn Santo, director of the Lakeside Presbyterian Preschool. “Before COVID it was getting hard ... now it is a next-level hard.”

One-year-old Julian, standing, plays with Lucy Arevalo as the other children play on the floor.(Eduardo Contreras / The San Diego Union-Tribune)

But for some providers like Algorri, the work still feels worth the long hours and low pay.

She sees herself in the people she serves — low-income parents, many immigrants like herself, working long hours to provide for their families.

She has served children whose parents work at 24-hour taco shops, KFC and Walmart. She has had families drop their kids off at 9 p.m. to work for border protection, at 1 a.m. to head to work providing meals for airplanes, and at 4 a.m. en route to work at Camp Pendleton.

Several speak limited English and don’t know where to go for key services, she said. Some don’t know how to open a checking account, do their taxes or sign up for English classes.

So Algorri shows them. Like many child care providers, she serves as a one-stop hub offering more than care. She has helped connect parents with everything from food pantries and immigration services to parenting classes and speech and occupational therapy assessments.

“I’ve lived it myself ... I understand the demographic of the community, and more than anything, I am a parent myself,” Algorri said. “I’ll do whatever I can on my end for those families to thrive.”

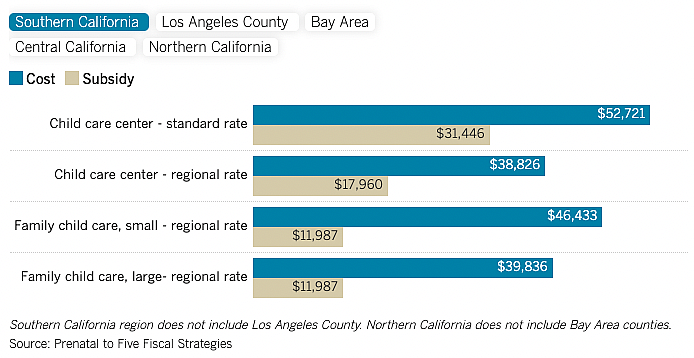

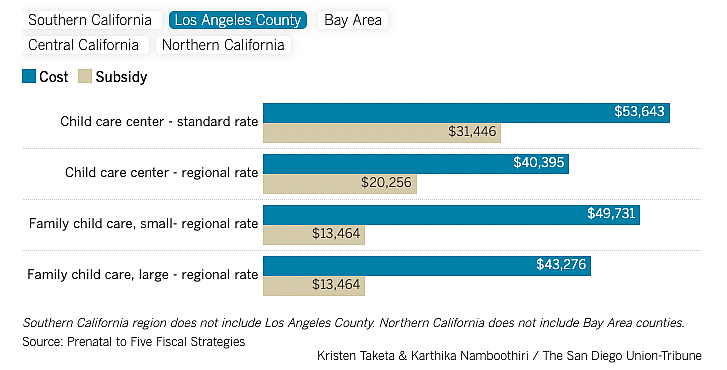

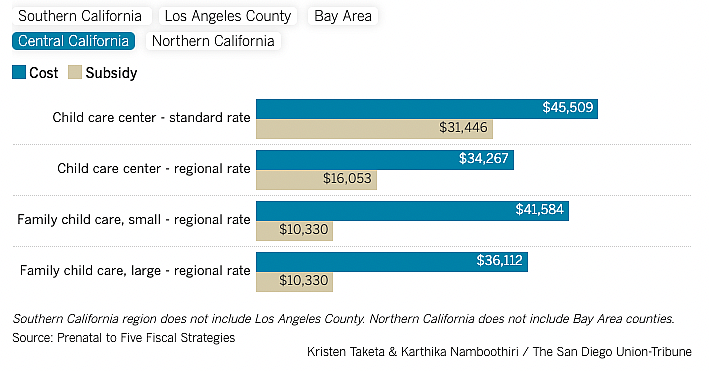

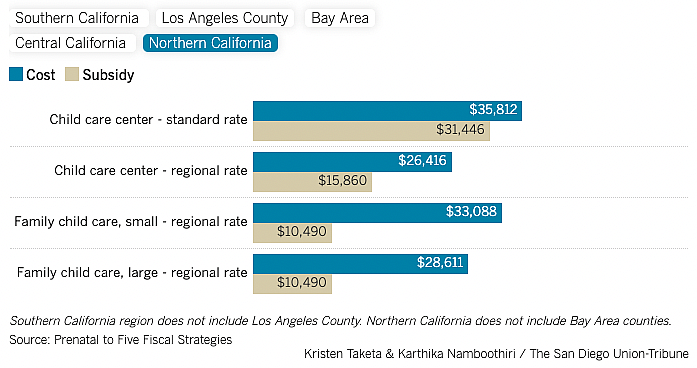

Prices families pay vs. providers’ true costs

For more than a decade, child care leaders in California have been calling for an overhaul of the way the state funds child care. Now even state officials like Gov. Gavin Newsom have agreed to study potential reforms.

For one thing, payment rates for providers are not regularly raised over time in line with inflation, but rather are decided by lawmakers at their own discretion.

For much of 2021, the state was still using 2016 child care market price data to decide some providers’ rates.

Later that year, the state agreed to update its maximum reimbursement rates and base them off 2018 market prices. Today the state still uses that nearly 5-year-old data to decide rates.

Yet market prices have risen significantly since then. Between 2018 and 2021, child care prices rose by 8 to 23 percent, depending on the age of children and type of care, according to a 2021 state price survey — and that was before consumer prices began rising even more sharply over the past year.

“We’ve had a global pandemic and record-high inflation. The reimbursement rates we’re paying them are based on a market that no longer exists,” said Donna Sneeringer, chief strategy officer for the Child Care Resource Center, a child care referral agency in Los Angeles County, and co-chair of a 2018 working group on rate reform for providers. “We really need to compensate providers based on what it is taking them to operate in 2023.”

The state pays providers using two kinds of subsidy rate systems, depending on which state program providers are part of. One of those rates is based on market prices by region, while the other is the same for providers statewide — meaning providers in the same communities can be paid at different rates based on which state program is paying them.

But beyond that, child care experts say there’s a more fundamental problem with the way California and most other states pay providers: They generally set payment rates based on the prices families have been paying for care, rather than on how much it actually costs providers to provide it.

Using market price data was long the only way states determined how much to reimburse providers of subsidized child care — for decades, the federal law that first authorized state-subsidized child care programs required them to.

This differs markedly from how the state funds public K-12 education — which, unlike child care, is guaranteed for every child in California and funded based on their needs.

Experts say it’s flawed to base payment rates for child care providers off of market prices, because those prices come from a market economists say has already failed.

“California’s state subsidy reimbursement rate structures have been woefully inadequate to address this market failure,” a state-commissioned working group of dozens of experts declared in an August report about the need for higher reimbursement rates.

Child care is by nature too expensive for most families to afford on their own, so market prices often reflect only the limited amounts parents can pay.

Many child care providers told the Union-Tribune they set their prices lower than what they should charge to cover their costs, knowing families simply can’t pay more.

“Although high-quality care would pay off in the future, it’s not something that parents can afford right now on their current income,” said Jessica Brown, an assistant professor of economics at the University of South Carolina who has studied the child care market and subsidies. “The system is basically limited by the income that the parents are making.”

To cure this market failure, Brown suggested that governments fully fund subsidized child care programs and raise payment rates so that more providers can enter the market.

Currently, the U.S. ranks toward the bottom among the world’s developed nations when it comes to public spending on child care.

The child care industry has long been underfunded and underpaid in the U.S., experts say, because the country has historically undervalued the work of child care and the people who perform it — starting with the enslaved Black women once forced into it.

It’s no wonder, advocates say, that current policies and norms reflect an implication that women — particularly women of color — don’t have to be paid much, if at all, for the care they provide. By extension, these norms also mean that governments don’t have to pay to ensure all families can afford child care, advocates say.

“Centuries of racist and sexist policies have resulted in chronic underfunding for early learning and care programs and an overall failure of government to treat early learning and care services as a public good,” the state working group wrote in its August report.

‘You have to pay what they cost’

In 2021, as a result of negotiations with California’s fledgling child care providers union, Newsom signed legislation with hundreds of millions in new funding for child care.

Among other things, the law set aside money for tens of thousands of new subsidized child care slots and approved hundreds of millions in temporary reimbursement increases and stipends to child care providers.

It also ordered the state to convene the working group to study how to reform California’s reimbursement rates for subsidized child care providers — which resulted in the August report.

To inform the group’s work, a national firm called Prenatal to Five Fiscal Strategies came up with estimates of how much it costs in California to provide child care that both meets the state’s quality requirements and that pays workers a living wage and benefits.

The children and teachers sing their good-morning song at Miren Algorri’s family child care.(Eduardo Contreras / The San Diego Union-Tribune)

The firm found that the gap between how much California pays providers per child and how much it costs to provide quality care is more than $10,000 per child, per year, in almost every region of the state for every age group of children who are not old enough to attend school yet.

In several regions — particularly in high-cost areas such as San Diego County, Los Angeles County and the Bay Area — that gap widens to more than $20,000 per child.

For example, in the Southern California region that includes San Diego, the cost to take care of one infant at a child care center that contracts directly with the state is $52,721 a year. The state covers only 60 percent of that cost for the center, for an annual shortfall of $21,275 per child.

For preschoolers at those child care centers, the state covers a smaller percentage. It covers just 38 percent of the annual $33,938 cost that Prenatal to Five estimates it takes to care for one preschooler, an annual shortfall of $20,970 per child.

The gaps are even wider for home-based family child care providers.

In Southern California, Central California and the Bay Area, the state is paying family child care homes that accept voucher subsidies anywhere from $25,000 to $39,000 less per child, per year, than what Prenatal to Five estimates it costs to provide quality care for infants, toddlers and preschoolers.

In Southern California, the state covers only about a quarter of the cost for small home-based family child care providers to take care of young children, and less than a third of the cost for large ones, according to Prenatal to Five’s estimates.

Southern California region does not include Los Angeles County. Northern California does not include Bay Area counties. Source: Prenatal to Five Fiscal Strategies

Southern California region does not include Los Angeles County. Northern California does not include Bay Area counties. Source: Prenatal to Five Fiscal Strategies Kristen Taketa & Karthika Namboothiri / The San Diego Union-Tribune

“When you start thinking about child care as a public good ... then you start saying: Well, shouldn’t the government be paying for high-quality care that has the high-quality outcomes, not just babysitting?” said Simon Workman, principal at Prenatal to Five, who has developed tools to estimate the true cost of child care for the federal government and other states. “In order to do that, you have to pay more than what families are paying. You have to pay what they cost.”

The gaps between subsidy rates and the true cost have discouraged child care providers from serving families through the state’s subsidized programs, said Lucia Garay, educational consultant and retired executive director of early education programs for the San Diego County Office of Education.

That in turn, she said, has limited how many subsidized child care spots are available for families who need it.

What goes into the cost of care

Currently, the highest rate that the state pays Algorri per child is about $12,000 a year, for an infant.

Meanwhile, the true cost for a family child care home like Algorri’s to take care of an infant in San Diego County is $39,836 a year, according to Prenatal to Five’s estimates.

Algorri says she doesn’t receive enough money to cover all her expenses, which range from insurance to her home’s mortgage to gas for picking up older children from school. She can afford to pay her assistant teachers only a little above minimum wage.

Southern California region does not include Los Angeles County. Northern California does not include Bay Area counties. Source: Prenatal to Five Fiscal Strategies Kristen Taketa & Karthika Namboothiri / The San Diego Union-Tribune

Algorri gets some reimbursement for food, one of her biggest expenses, through a government child nutrition program. But because she serves children for longer hours and feeds the children more meals and snacks than she is paid for, that reimbursement falls short of her food bill by about $7,000 a year, she said.

But as for most child care providers, her biggest expense is labor.

The state requires teacher-to-child ratios that providers must follow in order to maintain their licenses, ratios that are in place to ensure health, safety and quality.

For example, centers that provide state-subsidized care can have no fewer than one adult for every three infants, one for every four toddlers and one for every eight preschoolers — ratios in line with federal recommendations.

If a child care teacher who takes care of three infants is paid $47,304 a year — the income required to make ends meet in San Diego County for a single a

dult with no kids, according to the Massachusetts Institute of

Southern California region does not include Los Angeles County. Northern California does not include Bay Area counties. Source: Prenatal to Five Fiscal Strategies Kristen Taketa & Karthika Namboothiri / The San Diego Union-Tribune

Technology’s Living Wage Calculator — then that means the cost to provide care for each of those infants is at least $15,768 a year, just for their teacher’s salary.

That’s not taking into account any of the other costs of running a child care business. According to Prenatal to Five’s estimates, salaries typically

make up more than half of a child care provider’s expenses, followed by employee benefits, administrative costs, program supplies like food, classroom materials and medical supplies, then facility costs like rent, mortgage and maintenance.

The rate reform working group’s August report — which gathered input from more than 70 child care experts, state officials, providers and parents — recommended last year that California adopt a single, uniform rate system that is based on cost estimates, assumes living wages for child care workers and factors in regional costs of living. The recommendations echoed those that a similar working group had already outlined four years prior.

The federal government has allowed states to base child care subsidy rates on something other than market prices since 2014. Only three places have made the switch so far, Workman said: Virginia, New Mexico and Washington, D.C.

The challenge, he said, is the expense. If California chose to fund the full cost of care, the state would need to agree to pay as much as four times the rates it now pays some e providers, depending on their region, type and children’s age.

Southern California region does not include Los Angeles County. Northern California does not include Bay Area counties. Source: Prenatal to Five Fiscal Strategies Kristen Taketa & Karthika Namboothiri / The San Diego Union-Tribune

California officials said they are working on creating a new reimbursement system in light of the working group’s recommendations. But it’s unclear how soon such reforms will happen, as the state is predicting a $22.5 billion budget deficit later this year.

“It would be huge if California were to move on this,” Workman said. “You need the political will, you need the funding and all of the child care providers to be bought into this approach.”

The trouble with TK

Asked for comment for this series, the first thing a spokesperson for the governor’s office touted was the ongoing expansion of transitional kindergarten, a new grade level for 4-year-olds that is the keystone of Newsom’s plan for free universal preschool.

“California is transforming education, empowering students and families with more supports, more choices, and more opportunities,” the spokesperson wrote in an email. “Regardless of a family’s income or immigration status, California’s children will now have access to crucial education by age four — and we’re also making unprecedented investments to support subsidized child care across the state, in addition to the ongoing review of child care rates.”

The expansion of transitional kindergarten will bring more kids — and with them more money — to public school districts that for years have raised alarms about enrollment declines, which reduce their funding.

But Newsom’s biggest early learning initiative leaves out private child care providers entirely, threatening to take 4-year-olds away from the industry that has been educating them for decades — and that relies on them to stay in business.

Many providers count on preschoolers to make up for the money they lose caring for infants, who cost the most to care for because they require more adults for fewer children. “The older kids are basically what keep a lot of these centers afloat,” said Brown, the economics professor.

Assistant teacher Karina Palomino, left, pours milk for Julian and Ares, both one year old.(Eduardo Contreras / The San Diego Union-Tribune)

With fewer 4-year-olds, child care providers said they have had to take measures like reducing employees’ hours. Some are now trying to open infant and toddler programs for the first time but struggling to find the staff for them.

Andrea Laub, director of the Lakeside Montessori child care center, said she is down a dozen preschool students because families are going to transitional kindergarten instead. So she had to cut teachers’ hours from eight to four or six hours a day, further shrinking their already-thin paychecks.

“I don’t want to have to look at teachers and say, ‘I’m sorry, I have to lay you off because the public schools are taking all your kids,’” she said.

Child care advocates also argue that transitional kindergarten won’t help alleviate the child care shortage, because school districts don’t serve kids outside of the school day and school year. Many districts’ transitional kindergarten programs last only three hours a day.

“Universal TK is a wonderful talking point, and it sounds great,” said former state Sen. Connie Leyva, D-San Fernando Valley. “But candidly, most of us women call it ‘dude daycare.’ Because it’s three hours. What woman is going to drop off her child for TK, go work for three hours, then come and pick the child back up?”

Leyva, who was a member of the legislative Women’s Caucus until she left office last year, authored multiple child care bills, including one that would have established a single reimbursement rate system based on cost rather than market prices.

Another bill she authored would have let private child care providers in on transitional kindergarten funding through a mixed delivery system, which is used in other states including Washington and North Carolina. The bill passed the Senate but died in the Assembly’s education committee.

To many child care providers, their exclusion from transitional kindergarten speaks to long-standing disparities in funding and treatment of workers between the public K-12 school system and the largely private child care industry, even though both perform essentially the same job — educating kids and preparing them for healthy and productive lives.

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the average kindergarten teacher in California made $85,760 in 2021. A child care worker, meanwhile, earned just $35,390.

In the public school system, teachers get summer vacation, weekends and health and retirement benefits. In the child care industry, many providers are open from 6 a.m. to 6 p.m. — sometimes longer — and have no summer vacation, and sometimes no benefits.

In the public school system, nearly two-thirds of teachers are White. In the child care industry, more than two-thirds are women of color.

Providers point back to the way care for young children has long been undervalued.

“Our challenge is to show we aren’t just caring for kids ... it’s also education,” said Ken Herron, who runs the Herron House Preschool Center near Fresno and is a public policy advisor for early education advocacy group EveryChild California. “It will never happen if people believe we’re just babysitting kids.”

‘A higher chance of thriving’

Julian plays with a toy as Miren Algorri’s assistant teachers play with the other children.(Eduardo Contreras / The San Diego Union-Tribune)

In many ways, Algorri has been just as underserved as her students’ families.

Born in Tijuana and raised in central Mexico, Algorri started working in child care at 17 as an assistant for her mother’s home child care business in Spring Valley.

At the time, college wasn’t much of an option: Since she didn’t understand English well, she missed the testing and application deadlines — plus she had no transportation, and couldn’t have afforded tuition anyway.

Five years after she started working, Algorri married and gave birth to her first of two daughters. At 23, she opened her own family child care business to work with her daughter by her side.

“I did not want to leave her. I did not want to miss anything,” she said.

Algorri had trouble getting by after she and her first husband divorced. She no longer had a spouse’s income to make up for how little she earned in child care.

So she worked more.

The children and the teachers go outside to play in the yard.(Eduardo Contreras / The San Diego Union-Tribune)

She earned more state subsidy funding by enrolling more kids, serving them at all hours of the day to stay within her legal capacity — often by working overnight and on weekends. Some years, she says, she never took a day off.

And when she had to, she borrowed money — whether from her family, with a second mortgage or by taking on credit card debt.

Algorri has always had another option to cover her financial shortfalls: She could ask her families for a weekly copayment. Providers can charge families the difference between their subsidy payments and their expenses.

But Algorri won’t. As underserved as she is, she says she would rather shortchange herself than take money from other underserved families.

She’s not alone. About 44 percent of family child care providers and 31 percent of child care centers said they don’t charge families a copayment, compared with 27 percent of family providers and 38 percent of centers who do, a 2021 state survey found.

“I know that by not having a copayment, the families have a higher chance of thriving by having that money to buy food or pump gas or pay their electricity bill — whatever their needs are,” Algorri said.

On top of running her business, Algorri organizes with the state child care providers union and takes college classes — she’s working toward a bachelor’s degree in early childhood development. She stays up as late as 1 a.m. to complete essay assignments.

It took Algorri 20 years of studying, between taking care of other people’s children and raising two daughters as a single mom, to finally earn her associate’s degree.

She graduated from Southwestern College with honors in May 2019, on the same day her daughter graduated from Columbia University.