Part I: Evictions are surging, and children often pay the price

The story was originally published in CT Mirror with the support from USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism’s 2022 National Fellowship and the Kristy Hammam Fund for Health Journalism.

“This place is a mess. I hate living like this,” Tanya Austin said. As of October, she was staying at a shelter and Dexter, her son, was staying with his grandmother.

(YEHYUN KIM / CTMIRROR.ORG)

Click here to read the story in Spanish

The remnants of Dexter Menyfield’s childhood are crammed into a storage unit. To yank out a garbage bag full of clothes is to nearly send his old Hot Wheels rolling. An attempt to free his mother’s porcelain elephant dislodges his X-Box, which teeters before he grabs it.

Since he and his mother, Tanya Austin, were evicted, they’ve been back and forth to the West Haven storage unit several times, grabbing his school clothes, winter coats and blankets to make their hotel room cozier. Tanya’s social security checks just cover the unit, and they hope to unpack at a new place before the holidays.

It’s not the first time the 15-year-old has been homeless. But his memories of homelessness when he was younger are scant.

He greets the photo of himself, age 4 and dressed for karate, with an embarrassed smile and his mother’s declaration that they were living in their van at the time with an incredulous “We were?”

Tanya and Dexter were evicted in late August from a West Haven apartment they’d lived in since 2018. The landlord stated in filings that the lease had expired. Tanya says she and the landlord were in conflict for months ahead of the filing. Now, she and Dexter are living apart much of the time — he’s living at his grandmother’s house in West Haven while she stays at a New Haven homeless shelter. He sees his mom at the shelter on weekends.

They are far from the only Connecticut family struggling with the loss of their home. Since early pandemic-era protections against eviction expired, the number of filings has spiked as rents rise, inflation impacts budgets and families continue to struggle to recover financially from the pandemic.

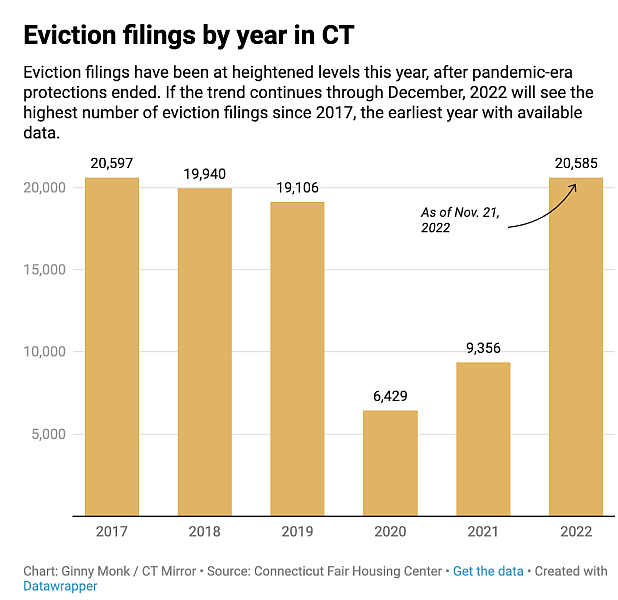

With about a month left to go in the year, the number of filings in 2022 had reached 20,585, surpassing the total number of filings in 2019 by nearly 1,500. Each of these filings can affect multiple people, depending on how many are in the household.

The rise in evictions has had an outsized impact on children, particularly on their health, education and mental health. It disrupts many aspects of life and separates families, leaving kids worrying about where they’re going to sleep, if they’ll have enough to eat, if they’ll be forced to stay somewhere unsafe.

Chart: Ginny Monk / CT Mirror. Source: Connecticut Fair Housing Center

Women and people of color, particularly women of color, are more likely to be evicted. Families with children are also at higher risk of eviction, studies show, although the number of children who face eviction are more difficult to track.

“Children really thrive on predictability and routine and knowing what's going to happen,” said Jason Lang, chief program officer at the Child Health and Development Institute. “Home, particularly, is typically a safe place for kids. It's the hub of kids' lives. ...

“So when there's a sudden eviction … when that always happens without warning or without the child being aware of what's going to happen, it can threaten the child's sense of safety and predictability.”

During the months between when her case was filed in December 2021 and the August eviction, Tanya looked for a new place to live. She typically has a small but steady income from social security and the occasional home health care job.

But with the eviction on her record, it proved difficult to find somewhere new. The two stayed in the U-Haul truck they’d rented to move their furniture into storage. One shelter offered to let them stay at night, but they had to find somewhere else to be during the day. They’d often ride the bus to the park or around New Haven.

For a couple of weeks, Tanya paid for a hotel. She called the Department of Children and Families twice to report the situation in the hopes more government involvement would get them to housing more quickly.

A nonprofit later placed them at a Super 8, but Dexter had already developed a cough that wouldn’t go away. It lingered for weeks, through the first motel stay, where they got bed bugs, to the second that Tanya paid for, and to the third, the Super 8 where they stayed for several weeks and decorated so it would be homier.

“It takes a toll on people,” Dexter said of the situation, ending the heavy sentence, as he always does, with a light laugh.

National housing experts have warned for months of an upcoming tsunami of evictions because people with lower incomes have struggled to recover financially from earnings losses caused by the pandemic.

That tsunami is now upon us, Connecticut experts say.

“There are definitely tenants who are still struggling,” said Elizabeth Rosenthal, deputy director at New Haven Legal Assistance. “And I think it's made worse by rising rent prices and by inflation in other areas. That's putting pressure on family budgets, which means they have less money that can go toward their rent.”

“I think we're only at the lower swells of the tsunami. I don't think we've seen the end of this rolling eviction wave, and I don't think we will anytime soon.”

What got us here

Evictions often occur within the court system.

Many researchers and housing experts also include forced move-outs under the umbrella of eviction. For example, sometimes a tenant must move out by a certain date under a court mediation, but a marshal doesn’t come to physically remove them. In other instances, landlords will push renters out through tactics such as turning off the heat or refusing to make other repairs.

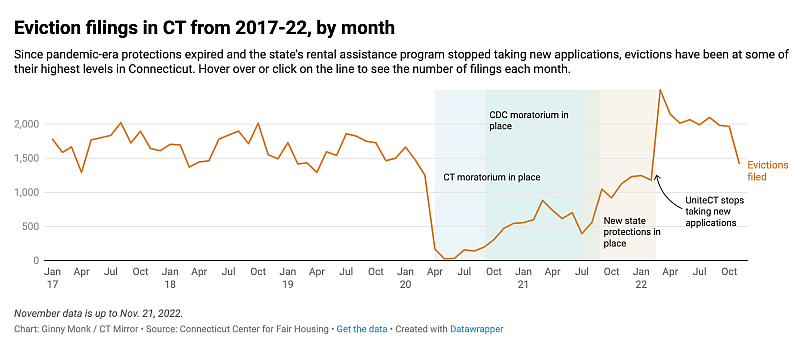

Since the early pandemic protections expired, evictions have surged in Connecticut.

In September 2020, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention issued a ban on most evictions for nonpayment of rent. The order aimed to prevent the spread of COVID by keeping people from entering congregate living settings such as homeless shelters.

The U.S. Supreme Court overturned the order in August 2021, which led to a quick spike in evictions nationwide.

In January, the number of monthly filings statewide had risen to 1,245, up from 395 in July 2021 when the federal moratorium was still in place. And they’ve risen since.

But some jurisdictions, including Connecticut, had state-level protections in place.

The state’s eviction moratorium ended in June 2021. When that order expired, Gov. Ned Lamont mandated that landlords have a UniteCT case number, meaning they’d applied for the rental assistance program, in order to file an eviction for nonpayment of rent.

Tenants also had 30 days to vacate a property after an eviction, rather than the typical five.

While the initial $400 million of the UniteCT program lasted, it kept thousands of people in their homes, housing attorneys reported. There were barriers, however. Many tenants said their landlords wouldn’t participate in the process, and landlords reported frustrations with a slow payment process.

The program has assisted about 47,700 tenants.

Connecticut’s additional protections expired in February, about the same time UniteCT stopped taking applications. Eviction filings leapt up again.

Chart: Ginny Monk / CT Mirror Source: Connecticut Center for Fair Housing

Landlords filed 2,497 evictions in March, the highest number of filings in a month since at least 2017, the earliest year with data available.

After losing money waiting for tenants to pay rent or for rental assistance payments, and with inflation affecting operating costs, it’s harder for landlords to wait for people to catch up on rent, especially if they are a newer, less-established tenant, said John Souza, president of the CT Coalition of Property Owners.

The coalition is an organization for landlords in Connecticut. Souza often speaks in legislative hearings on bills that could affect landlords.

He added that landlords don’t like to evict people, but there’s not another system in place.

“Nobody feels good about it, but sometimes you don’t have a choice,” Souza said.

He said more rental assistance might help, particularly if it was a simple process for landlords.

In October, Lamont announced that the state had received an additional $11 million in federal money. It’s being dispensed through the state’s rent bank program, which was initially funded with $1.5 million during the 2022 legislative session.

“It won't be enough,” said Giovanna Shay, litigation and advocacy director at Greater Hartford Legal Aid. “But there will be something. For a time here since UniteCT shut down, there really wasn't anything to offer folks.”

More help needed

One gauge of the need is the state’s 211 hotline, which receives an average of 1,000 requests for help every day from people like Tanya in a housing crisis, according to the United Way dashboard from the past year.

Tanya has reached out for help everywhere she can think of, and she even spent one rainy day walking around New Haven trying to meet caseworkers and get her and Dexter’s paperwork, such as birth certificates and vaccination records, in order so she could be ready with any information needed to get them back in housing.

Dexter Menyfield, 15, right, talks to his mom, Tanya Austin, while waiting for an Uber outside a motel where they were staying. "He doesn't have to go through this," Austin said. "This 15-year-old, he needs his own space." YEHYUN KIM / CTMIRROR.ORG

She’s struggled watching her son go through homelessness, and it weighs on her that she can’t find a place for them. She finds solace in prayer and walks by the river. One of the best things about the Super 8 was its proximity to the river.

“You wake up in the morning, and you don’t know where your son is going to sleep, you don’t know what he’s going to eat,” Tanya said.

Things were better at the Super 8 in West Haven. They pulled off th hotel bedspreads dotted with cigarette burn marks and made the beds with their own comforters from the storage unit. Tanya didn’t like the smell of the Fabuloso the hotel uses to clean, so she bought Pine Sol to scrub the floors and lit votive candles in the windowsill to connect them to God.

“No matter where we stay, I’m going to make it comfortable for him,” she said.

About a month ago, when they had to move to a New Haven homeless shelter, Tanya opted to have Dexter stay at her mom’s.

Tanya can’t stay with them because two adults in the apartment might put her mom at risk of an eviction, she said. There was no more money for the motel, and in order to fulfill the requirements for rapid rehousing programs, they had to be “literally homeless” – a term that is used by advocates to prioritize people for housing who live in shelters or on the streets.

Rapid rehousing refers to programs that quickly put people in housing, often through rental assistance and other services.

Tanya Austin and her son, Dexter Menyfield, 15, shared one bedroom at a motel for a few weeks after eviction. "We went from three bedrooms to a room. This is how we gotta live," Austin said. YEHYUN KIM / CTMIRROR.ORG

The move to the shelter sent Tanya spiraling. She considered suicide when she saw the room at the shelter, she said, and spent a couple of days at the hospital where she stabilized.

“I just can’t wait to get out,” she said of the shelter. “I can’t wait to get my own place again.”

Who gets evicted

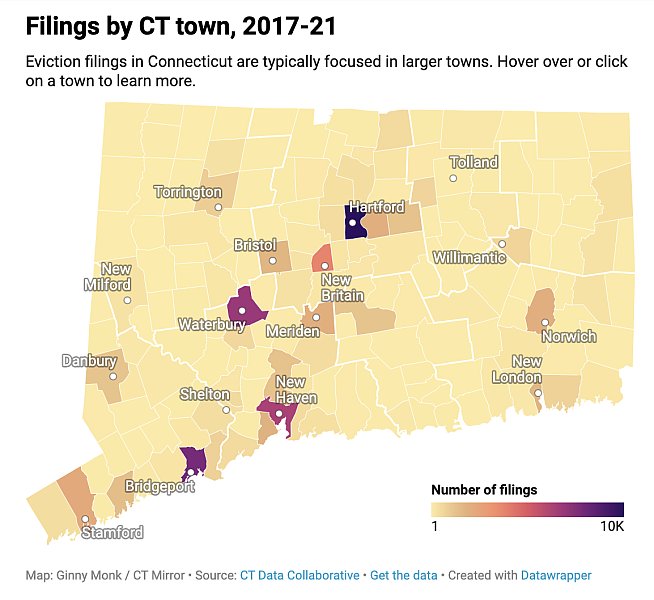

The bulk of eviction filings are in cities such as Hartford, New Haven, Waterbury, New Britain and Bridgeport. All of those except New Britain are on the Princeton Eviction Lab’s list of top evicting cities.

Those areas are also parts of the state with the largest minority populations.

“It’s Black women, isn’t it?” Tanya asked one day, when presented with the rising number of evictions.

Tanya and Dexter walk out of a motel that they were staying at. Before they moved into the motel after eviction, they spent a couple of nights under the bridge. Without having cooking furniture, they had to rely on instant food. YEHYUN KIM / CTMIRROR.ORG

She’s right.

In Connecticut, Black renters are more than three times more likely than white renters to face eviction, while Hispanic renters are more than twice as likely to face eviction, according to a CT Data Collaborative and Aurora Foundation report. The Aurora Foundation is a nonprofit that conducts research and distributes grants that deal with issues related to women and girls.

Historic, systemically racist policies mean that people of color are less likely to have as much accumulated wealth or own their homes, researchers say. This means they’re more likely to experience housing instability.

From 2017 to 2021, more than half – 56% – of evictions in Connecticut were filed against women, according to the Aurora data report.

They tend to earn less money, and more women than men are single parents, research shows.

“A single mother with children is probably going to be more vulnerable in a variety of ways,” Rosenthal said. “Potentially being late on the rent because they lost hours at work because a child was sick, or being late on the rent because a child needed new shoes, or being late on the rent because they had to make a difficult choice between feeding their child or paying their rent.”

Map: Ginny Monk / CT Mirror Source: CT Data Collaborative

Gender dynamics can also play a role, according to a study from Matthew Desmond, an eviction researcher and founder of the Eviction Lab. Some of his earlier work included a case study of evictions and their effects on tenants in Milwaukee.

Women more often tend to try to work behind the scenes to fix the problem, all while avoiding their landlord. But men are more likely to confront the problem head-on, offering to conduct work around the complex in exchange for rent or working out a payment plan, Desmond writes.

“I think people that do this work understand that women of color are always the most vulnerable and are going to be the hardest hit,” said Jennifer Steadman, executive director at the Aurora Foundation. “But this report, being able to lay that out, make it very clear that particularly Black and Latina women are disproportionately affected by evictions, that they are often single moms, single female-headed households, that didn't surprise me, but I feel like it's one of the most powerful pieces of this report.”

Families with children like Tanya and Dexter are often at higher risk of eviction. Housing code violations can draw the attention of child welfare, and children, particularly when they’re crowded into apartments, can cause damage to the rental. Landlords often don’t like the additional scrutiny, Desmond writes.

Families with children also typically have more expenses than single people or couples, Shay said.

They often need a larger space and have to pay for child care or cut back on working hours in order to take care of the kids, Shay said.

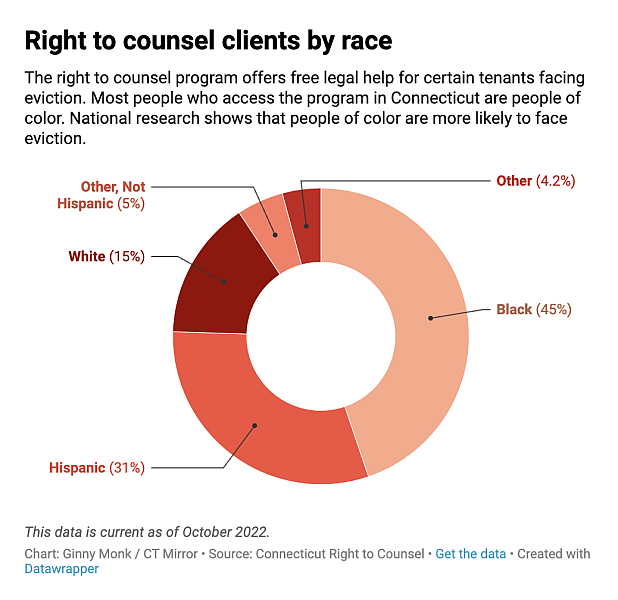

Chart: Ginny Monk / CT Mirror Source: Connecticut Right to Counsel

It’s difficult to track exact data on the number of children who are evicted. Kids aren’t typically listed on an eviction, so the court doesn’t have that data. But housing service providers and legal aid attorneys said they consistently see families with children going through eviction.

Data on clients in Connecticut’s right to counsel program shows that 63% of households in the program have more than one person in the house.

The human impact of these numbers translates to a reality in which women of color – and their children – experience the adverse impacts of eviction more frequently.

Health effects

Lailah Hall, 7, recently read a book for school called “Maybe Tomorrow,” a story about Elba, a pink hippo who is weighed down by the block of grief and sadness she drags around.

“It made her walk slowly. It made her think darkly. It was heavy,” the book says of Elba’s block.

Lailah, who is Black, has a broad smile and is happy to show off her ability to count all the way to 100, and super fast, too. But, like Elba, she drags a block. Her family is being evicted – they’ll have to be out of their Hartford apartment by the end of the month.

For the Hall family, the trouble began in 2020, soon after they moved into their apartment in the southern part of Hartford. They started having trouble with pests and asked the landlord to fix the issues, said Eboni Hall, the mother of Lailah and four other children who live with her, two adult children and a baby who died several years ago.

Lailah and her siblings can’t play on the floor because they’re afraid rats or mice will run out of their hide-y holes. They don’t even sleep in their new bunk beds because the rats climb the railings and run across them while they rest.

“It’s scary,” Lailah said in an interview at her home, perched atop one of the two chairs that occupy the kitchen. The dining room is crammed with boxes and bins her mother uses to try to keep rats off their belongings.

When they sleep, it’s her and the four kids on one mattress propped on milk crates, with the lights or the TV on so they can see the rodents scurrying across the floor.

Hartford’s Building Code Enforcement issued fines related to the violations in June 2021. The documents referenced problems with the refrigerator, bathroom shower tiles, porch door, and mice and rodents.

Eboni Hall stands in her apartment kitchen Thursday, Dec. 8. The Hartford apartment has a pest infestation, and earlier in the week, Hall had placed tin foil to cover a hole in the kitchen where mice were getting in. GINNY MONK / CTMIRROR.ORG

Evictions and poor housing conditions – two circumstances experts say are inextricably entwined – can lead to worse health outcomes both in the long and short term.

Eboni’s children are often sick, which she attributes to their living conditions.

Lailah’s monologue over whether Butterfingers or lollipops make a better Halloween treat are punctuated by deep coughs. An ear infection keeps her from hearing out of one ear, and she’s missed enough days at school that her family has an open Department of Children and Families case, said her mother.

After months of complaining to the landlord and nothing being fixed, Eboni decided to withhold rent. The lights in the hallway leading to the unit are out, so she has to use a flashlight to climb the stairs. And the outside is often littered with trash, so the kids rarely go outside to play.

Sometimes, as tenants grow frustrated with poor conditions, they’ll stop paying rent, said Rosenthal, of the New Haven legal aid group.

“If you have a fraught relationship with your landlord because they're not fixing things, and you are rent-burdened, it's easy to say, ‘Well, I have this other priority that I need to focus on. And I'm not going to focus on paying my rent because my landlord won’t fix things,’” Rosenthal said.

Eboni didn’t know Connecticut has an official process by which tenants can pay rent to the courts until code violations are remedied.

“It's really hard and frustrating because it's the winter,” she said. “It's the holidays. I just think it's unfair, that I've tried to reach out. I've tried to work with this company and they just continue to have the upper hand, and us little people just have to deal with it.”

Reached by email, Precision Property Management, the apartment building’s property manager, said they took over management in the summer and that some decisions were out of their control.

They added that since the pandemic, they are much quicker to file evictions and prefer to find a resolution in the judicial process.

“The unfortunate upshot of this is that extra costs are incurred such as marshal fees, court filing fees, and attorney's fees,” an emailed statement from the company read. “It sometimes creates a situation wherein a rental arrearage can increase beyond a tenant's ability to pay.”

Typically, Precision prefers to apply a criteria for eviction uniformly across the board. The company considers whether the tenant has made attempts to pay back rent.

They declined to comment on the conditions of the apartment.

“The Connecticut legislature has given careful consideration to how it drafted its landlord/tenant laws,” they wrote in a statement. “Tenants, similarly to landlords, are not allowed to self-help in certain circumstances. A tenant who believes they have the right to withhold rent has rights under the law; however, those rights need to be exercised as prescribed. One can't just decide one day they do not want to pay rent or make unilateral adjustments to their rent. If they do not follow the law then a landlord has no option other than to exercise their rights under the law.”

Housing conditions are a particular concern in Connecticut, where much of the housing stock is aging. The state and some municipalities have taken steps to address lead paint in homes, but tenants also reported issues with heating, plumbing and pests, among other problems.

More than half – about 59% – of right-to-counsel clients in Connecticut report that there are defective conditions in their homes, and the vast majority of those said they’d told the landlord about the problem, Walton said.

By the time Eboni’s eviction court date came around, the court mediator told her the case was meant to decide whether she’d paid rent, not whether the living conditions were up to code.

Repairs can also be expensive, landlord Souza said, which may be why some landlords hold off making them. While landlords should keep their properties up to code, they may need subsidies to make fixes and keep the apartments affordable, he said.

“Everybody wants affordable housing,” he said. “Everybody wants housing in good shape.”

Tenants who get evicted are sometimes pushed into worse housing conditions, Desmond writes. These conditions can cause lead poisoning, increased risk of heart disease and respiratory problems.

“One of the things that in some cases can lead to an eviction is residents, tenants who are complaining about unsafe or unlivable conditions and landlords basically choosing to evict as a form of reprisal,” said Peter Hepburn, a researcher with Princeton’s Eviction Lab. “The other way this flows is that people who get evicted are going to have a harder time finding housing in the future, so instead of being able to get into a good apartment, they’re going to have to settle for something downmarket. “

In addition to health concerns caused by housing conditions, displacement through eviction can cause a myriad of health problems.

It’s related to developmental problems, food insecurity, depression, anxiety, behavioral problems and disruptions in health care. When mothers experience housing instability during pregnancy, they’re more likely to give birth to premature or low-birth-weight babies, according to a 2020 report.

Research published last year showed that evictions were tied to higher rates of infection and death from COVID-19.

Evictions can impact health through stress and psychological effects. There are also environmental health effects related to housing conditions. Eviction also puts people at higher risk of contracting infectious diseases, and finances are stretched thin, meaning it’s harder to afford things like food and health care, Leifheit said.

“It's pretty hard to tease out what proportion of the health impacts will be related to physical aspects of the housing versus kind of the stress involved in displacement,” said Kathryn Leifheit, a researcher who examines connections between health and housing.

Psychological impacts

The experience of housing instability is new to Eboni. Before she moved to the apartment, she and the kids lived with her grandmother, Dorothy. Dorothy, who worked at a printing company, owned her house, and Eboni cared for her when she got sick.

When Dorothy died, her finances weren’t in order. The house had to be sold, and suddenly Eboni and her children were looking for a place to rent. The apartment in the South End of Hartford was in her price range — $1,150 per month.

Eboni keeps photos of generations of her family up on the walls of her home — many of them strategically placed to cover holes or chipping paint.

“Family is everything to me, especially with [her mother] being gone,” she said.

She wants to build a home for her children that feels safe — the way she felt in childhood.

Now, she’s working double shifts, often from 4 p.m. to 8 a.m. before she starts her “day shift” as a mom. While she’s at work, one of her adult children is home with the younger kids. Eboni rarely sleeps.

The hallway where Eboni Hall and her four children live. They are in the process of being evicted and have to be out of their Hartford home by the end of December. YEHYUN KIM / CTMIRROR.ORG

All that work is in service of building a new life for her five kids. In addition to saving thousands for a deposit on a new place, she has to replace many of her children’s belongings, she explained, because rats have chewed through clothes and toys.

She doesn’t want to let them play with or eat on any possessions the rats have touched, which rules out most of their stuff.

“It’s not an easy pill to swallow, starting from scratch,” she said.

The kids are experiencing heightened stress, she said. Sometimes, Lailah has to take breaks at school because she feels too anxious and overwhelmed to be in her third-grade classroom. Eboni’s 9-year-old son is in therapy, but she’s not convinced it’s helping.

“It won’t help as long as we're in this environment,” she said. “It's not going to work.”

She hasn’t found a new place yet and is preparing for the possibility of moving her kids into a motel.

“We don’t have the same options that white people have,” she said. “When we go into a bank or a car dealership, it’s different. … We have to work extra hard to fit in and find a place in America.”

The hallway where Eboni Hall and her four children live. They are in the process of being evicted and have to be out of their Hartford home by the end of December. YEHYUN KIM / CTMIRROR.ORG

Gary Steck, chief executive officer at Wellmore Behavioral Health in Waterbury, said his organization had seen an uptick in the number of people coming in with stress related to housing instability.

Tenants interviewed for this series consistently reported that their kids were having nightmares, wetting the bed and are often anxious, while children and teens told the Connecticut Mirror that they were worried about where they’ll live and go to school while grieving the loss of their personal belongings after evictions.

For kids, stress can also come from seeing their parents’ anxiety, Steck said.

“All kids are aware in the same way where they can just say ‘Oh, I noticed that mommy is stressed,’ but they absolutely are incredibly sensitive to the parents, caregivers and siblings and other people that are around them,” he said.

Christine Nucci, a therapist in Deep River, said kids sometimes experience grief when they are evicted.

“It’s pretty traumatic,” Nucci said. “Grief is incorporated into that for them, having to make new relationships. Oftentimes when kids leave and move, there’s no closure.”

And longstanding housing instability can leave children in a fight-or-flight mode for longer periods of time, affecting cortisol and adrenaline levels in the body.

“It’s a reaction,” Nucci said. “If you’re in crisis all the time, you’re on high alert.”

It can leave children with lifelong trauma, clinicians said.

For Lailah Hall, the immediate concerns are the rats and where her family will be for Christmas. She wants to be sure she gets to watch “the Chipmunk movie.”

Eboni says the kids will watch the movie. But she wants to give them a Christmas free of worry about housing, and full of gifts and music and cookies.

“They [the landlord] can't understand that because maybe they don't live that way,” she said. “And that's understandable too. But it doesn't mean ‘Be neglectful of the people that you rent to.’ Because we deserve to live somewhere that's decent and habitable just as well as they do.”

Right to counsel

Housing court in Hartford is a picture of juxtaposition — attorneys and court officials toting briefcases and file folders sitting alongside tenants clutching their evidence, some with babies propped on their hips.

The former understand the process and do this nearly every week. The latter are having one of the worst days of their lives.

On paper, the path to eviction is fairly straightforward. A landlord alerts a tenant they want them out — because of a lease violation such as nonpayment of rent, because they’ve become a “serious nuisance,” or their lease has expired — and the tenant receives what’s called a “notice to quit.”

If the tenant doesn’t comply within the given timeframe, the landlord can start proceedings against them in court, which usually leads to either a mediated agreement or a ruling in favor of one party or the other.

Tanya Austin moves an altar table, one of her most precious furniture, to take out clothes she and her son need. She used to decorate her previous house with the table, elephants, candles and angel statues with a Burgundy color theme, Austin said. YEHYUN KIM / CTMIRROR.ORG

But in reality, the path is often more winding, with nuance, arguments, attempts to fix the wrongs and sometimes several court filings.

During the 2021 session, lawmakers approved the use of $20 million in pandemic relief funds to establish Connecticut’s Right to Counsel program.

The program offers free legal assistance to low-income residents of certain ZIP codes and income-qualified veterans across the state. Connecticut is one of three states in the country with such a program.

Funds are on track to last until 2024 when advocates hope the legislature will allocate dollars from the state budget to keep it afloat, said Tiffany Wal

ton, grants program director at the Connecticut Bar Foundation. The Foundation oversees the program.

Legal aid services have hired additional housing attorneys to staff the program. Before it began, more than 80% of landlords had an attorney compared to 7% of tenants.

In those 15 ZIP codes, about 6% of tenants facing eviction had legal representation in 2019. In 2022, after the program launched, that rate had increase

Tanya Austin takes out belongings that she needs for the winter from a storage. After the eviction, she has kept many of her furniture and clothes in the storage. YEHYUN KIM / CTMIRROR.ORG

d to about 14%, Walton said.

Sherelle Allen, a New Haven resident, was one of those who got representation through right to counsel. She’s lived in her apartment for six years, and her landlord gave her eviction paperwork in October. He claimed she was partying and that her dog was a nuisance, both points she contested.

“I was kind of wrecked because I was pregnant at the time,” she said. “They [the landlord] wanted me to pay all these lawyer fees and stuff like that. It was just crazy, I was working, my kids are in sports and they just want to put me out on the street.”

With right to counsel, she was able to get legal representation that allowed her and her three children to stay in their home. The program has served more than 1,500 clients.

Cost of poverty

While the legal representation keeps some in housing, others still lose their cases. Tanya had free legal representation in her case, but after several weeks of b

Especially when you'd been living in a certain way, everything is suddenly turned," Austin said about her life after eviction. "That's how I felt." YEHYUN KIM / CTMIRROR.ORG

ack and forth in court filings, she lost her home.

Dexter attends a magnet high school in New Haven and acts in the school theater. He laughs easily and loves Sprites. He missed the first several weeks of school because his mom was afraid to send him off for the day, not knowing where she’d be when he finished class for the night.

It made it hard for him to catch up, but he’s pulled his grades up. Theater and lunch are his favorite parts of school, he says. He’s considering trying out for the production of Hairspray.

Since he was born, it’s been him and his mom against the world. She hasn’t dated anyone seriously so she could focus on her son.

The day they moved from the hotel to living separately, notifications flashed across his phone screen. His friends wanted to know why he wasn’t in class. He’d missed a quiz.

He doesn’t want to open up to his friends about their housing situation.

“It’s nobody’s business,” he says, with a shrug. He’s eager to find a new place, to have his own room again.

But it’s near impossible for people with eviction records to find housing in Connecticut now. Tanya has messaged dozens of landlords, even filled out a

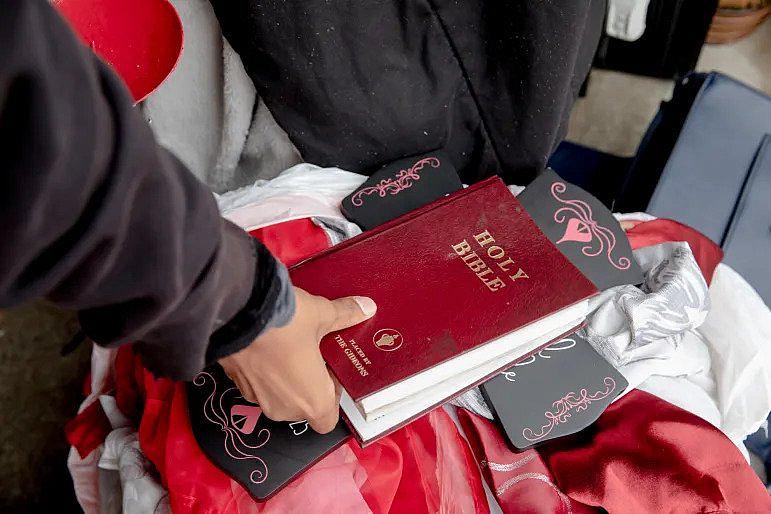

Dexter Menyfield, 15, takes the Bible out from the storage so his mom, Austin, can use it. When he and Austin were evicted and moved around between streets and hotels, he had to be absent from school for three weeks because they were not sure where they would stay for a long term. YEHYUN KIM / CTMIRROR.ORG

pplications, with no success.

Connecticut’s apartment vacancy rates are the lowest in the country, hovering around 2%, and rents are climbing.

“Not only are eviction filings topping pre-pandemic levels, but there just aren't a lot of places folks can go,” said Hartford legal aid’s Shay. “And we see that even for people with Section 8 vouchers, that they're just having difficulty finding units to rent that are in any way affordable.”

Section 8 vouchers refers to the federal housing choice voucher program, which offers people with low incomes assistance paying monthly rent.

Souza, of the Connecticut Coalition of Property Owners, said that it takes longer to evict tenants since the launch of right to counsel.

He said because tenants have representation, each eviction requires landlords to hire attorneys for longer periods of time. With that and other increased costs, he’s less likely to take a chance on someone with an eviction on their record, he said.

“People, they live close to the edge all of the time and their problems become my problems,” he said.

When they were first evicted, Tanya had about $7,000 cash for a deposit that she offered up to several landlords as proof she could afford an apartment. But as time went on, that money dwindled.

Dexter Menyfield, 15, takes out things that he needs for the winter from a storage. "I'm just hoping that Dexter doesn't have to go through this again," his mom, Tanya Austin, said. YEHYUN KIM / CTMIRROR.ORG

They had to rent the U-Haul to move their belongings. With nowhere to store food, they had to eat takeout or fast food more often. The monthly payments for their storage unit stacked up. And staying in a hotel was pricey before the nonprofit started covering the tab.

Dexter has been helping his mom look for places, a task that has developed into a hobby. He downloaded the Zillow app on his phone, and scrolls through listings during the day, clicking condos with high ceilings and sleek new cabinets, and apartments where he could have his own bathroom.

He says he wants to become a real estate agent one day. It’s good money, and he could find a place for him and his mom, he says.

His attitude through the ordeal and his advice for other kids going through eviction, he said one day while waiting for his mom to get checked in at the homeless shelter, is a simple method to keep in good spirits.

“Keep your expectations low and your vibrations high,” he said.

"Notice to Quit," a multi-part examination of evictions in Connecticut and their effects on children and families, was produced as a project for the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism’s 2022 National Fellowship and its Kristy Hammam Fund for Health Journalism. This project also was supported by the Center’s Engaged Journalism Initiative.