Black Caregivers Face Challenges Caring For Aging Loved Ones With Dementia

The story was co-published with Sacramento Observer as part of the 2024 Ethnic Media Collaborative, Healing California.

For the past seven years, veteran OBSERVER photographer Robert Maryland has cared for his 84-year-old father, Carl Maryland, who has dementia. Black families are more likely to be caregivers in at-home settings.

Photo: Louis Bryant III, OBSERVER

Growing older, African Americans often make a heartfelt plea to their loved ones: “Do not put me in a home.” This sentiment underscores a deep-rooted cultural emphasis on familial caregiving and a desire to maintain independence and connection to one’s community in the later stages of life.

It’s estimated that nearly 7 million people age 65 and older in the U.S. are living with Alzheimer’s disease. That number is expected to grow to 9 million by 2030. It is estimated that 65% to 75% of dementia patients receive care from family members. African Americans account for roughly 1 in 10 of the 15 million family dementia caregivers nationwide.

The responsibility of looking after those with Alzheimer’s and other dementias falls heavily on African American families, leading to significant stress and negative health outcomes for caregivers, such as cardiovascular problems, chronic conditions like diabetes and obesity, lower immunity, increased headaches and back pain. Research suggests they may face heightened risks, yet their experiences are often underrepresented in studies. Addressing this disparity is crucial for developing culturally competent and effective support systems.

Retired photographer Larry Dalton is mourning the loss of his significant other, Kathy Charles, whom he saw change as her dementia rapidly progressed. The two lived together locally before Charles was moved to a care home, where she sadly passed in October.

Photo: Louis Bryant III, OBSERVER

Longtime OBSERVER photographers Robert Maryland and Larry Dalton became their own support system when they both found themselves caring for loved ones facing cognitive challenges. They recently began sharing their families’ experiences as openly as they swapped tales of memorable photoshoots with celebrities and community icons.

The lens has always been on others, but now Maryland and Dalton find their own lives in focus, revealing their own struggles. They’re not just observers behind the lens; both are now experiencing firsthand the struggles they’ve long documented, forging a deeper connection with the community they serve.

Stepping Up To The Plate

Over the years, Robert Maryland has used his photography skills to capture moments in the life of his father, Carl Mayland. A photo of his father showing off championship rings he won with his senior baseball teams is mounted on the wall of the 83-year-old’s bedroom suite. Carl, who almost went pro in the 1960s, traveled the country playing softball in his later years. Some of his old baseball caps are also on display in his room.

Robert recalls the time he took his father out to a local baseball field, knowing it would likely be his last time at bat. Instead of a baseball uniform, the former shortstop wore pajama pants and slippers with his sweatjacket and hat. Robert remembers hearing players out on the field whispering about his father’s status as a legend. “That’s Carl Maryland. He has dementia,” he recalls them saying.

There was awe and sadness in the men’s voices.

While it’s unknown whether Carl heard them, understood that their words were about him or even knew where he was that day, he had a smile on his face, as did his son.

Robert has been caring for his aging father for the last seven years. The two live in an Elk Grove home they bought together. Prior to the purchase, the elder Maryland resided in a local senior living community. Legendary baseball manager Dusty Baker’s mother was his neighbor.

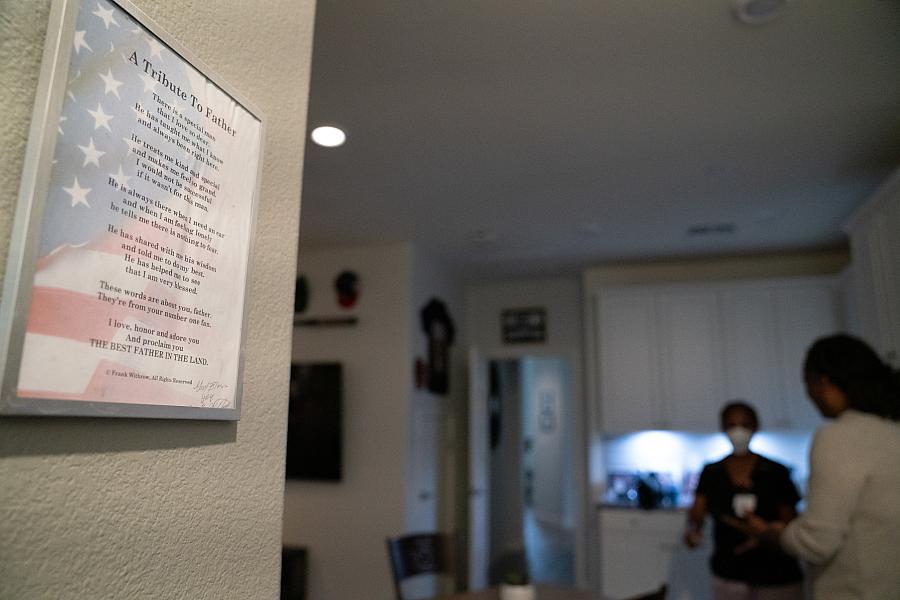

Robert Maryland discusses his father’s care with a visiting nurse.

Louis Bryant III, OBSERVER

“It was a nice, top-of-the line place,” Robert Maryland says. “It was very expensive but, hey, it’s my dad.”

Carl was doing well there. He cheerfully helped other residents and was popular among the ladies. Always a sharp dresser, Carl got himself ready every day and still drove his own car. The facility found his driving to be a liability, however, and asked Robert to remove the car from their site.

“My dad said, ‘Rob, I don’t want to live here anymore.’”

Rather than continue paying $4,000 a month for his father’s stay, Robert took his mother’s advice that the two men purchase a home.

Maryanne Maryland’s support would surprise some, as she and Carl had an acrimonious divorce in 2018. The two were married 61 years and had been together since their teens. While no longer together, Maryanne comes over often and sits with her ex-husband while Robert is out on assignment or handling other business.

“My mom always says, ‘I’m not here for Carl, I’m here to help my son out.’ I respect that,” he says.

Robert is the youngest of Carl and Maryanne’s three adult children. They’ve discussed the likelihood of her being able to care for her ex-husband had they not separated.

“It would have been too much work for her because she’s an older woman too,” Robert says.

His mom turned 83 in October and has had a knee replacement and several rotator cuff surgeries.

“She’s too weak to change him,” Robert says of his mother’s physical limitations. “She helps me out, she feeds him. I do the changing and the stretching of his body and stuff.”

Robert was lifting his father out of bed, getting him to the bathroom and into the shower every day, before his mother showed him how to bathe him in bed.

Maryann Maryland feeds her ex-husband Carl Maryland.

Photo: Louis Bryant III, OBSERVER

“I didn’t know,” he says. “I wasn’t trained to do anything, but I’ve got it down now. I’m a master.”

The physical exertion, however, had already taken a toll on Robert, a grandfather himself who turns 62 in January.

“To this day, my shoulders still hurt from lifting dead weight,” he says.

Most people don’t think about the realities of taking care of an older person with dementia until they have to. It’s rarely pretty.

“I didn’t think I could do that either,” Maryland says. “He’s my dad first of all, but then I’m seeing this man there and he can’t do it. He can’t change himself. He can’t even get up to go to the bathroom anymore.”

His father has been bedridden for most of 2024 and doesn’t talk much.

“His memory is off and on,” Robert says. “He’s there, then sometimes he’s gone.”

It’s a stark difference from when they first moved into the new house.

“He got dressed every day. He’d sit outside. He’d mow the grass. He was still Carl Maryland.”

Help Wanted

Despite affecting more whites, African Americans and Hispanics face a higher risk of Alzheimer’s due to health care barriers such as discrimination, limited access and historical mistrust, leading to poorer health outcomes. The number of Black Americans with dementia is expected to quadruple by 2060, highlighting the urgent need for increased services and support for caregivers like Maryland and Dalton.

Locally, the Agency on Aging, Area 4, offers a number of low-to-no-cost services for caregivers ranging from meal delivery to home visits meant to give providers respite. ONTRACK Program Resources’ Soul Space program offers a number of free support groups aimed at helping people maintain mental health and emotional wellness.

“One of the brothers in my group has cared for his wife, who has been a close friend of mine for 43 years,” says Paul Moore, who leads Soul Space’s biweekly “Black Men: Alive and Well” sessions. “The mental respite he receives in this space is critical to helping caregivers feel less stressed and burnt out.”

Participants also receive one-on-one interaction with empowerment advocates who link them to needed community resources.

The National Caucus and Center on Black Aging Inc. offers online resources, as does the Alzheimer’s Association, which also has a 24-hour hotline. Organizations such as the Alliance with Black Churches and Alter offer resources for Northern California’s faith-based community. The UC Davis Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center provides a caregiver bootcamp class, covering topics such as memory support strategies, stress management techniques and navigating behavioral changes.

Been There

In her book “Get Ready, Get Set, Cuz, We’re All Gonna Go,” local author Beatrice Toney-Bailey reflects on caring for her second husband before he died of lung cancer. She also suggests seeking help from a professional mental health provider, joining a support group and maintaining one’s physical health.

“During this journey, I found out so much information and I just knew I had to share it with the world, hoping that someone will have less chaos in their lives,” Toney-Bailey wrote.

A career as a professional photographer can be chaotic. Job demands and the industry’s competitive nature often kept Maryland and Dalton apart. However, the veteran photographers’ bond deepened as they aged, particularly when they both found themselves dealing with a loved one’s dementia.

They started meeting for breakfast or lunch. While Robert’s father was at home, most of the time Dalton would bring along his longtime girlfriend Kathy Charles, who started displaying signs of dementia two years ago, following the pandemic. The two lived together and dated for 17 years before her tragic death in October at age 74.

“I’m devastated,” Dalton says of the passing of the woman he planned to grow older with.

Sometimes Maryland and Dalton dined with colleagues; at other times, it would be the two of them, discussing possible collaborations or talking shop, reminiscing about the good old days and how new technology has revolutionized photography. Charles would talk incoherently as they conversed or fork food that wasn’t on the plate in front of her. Dalton’s sister and other friends compassionately included her in conversations and accompanied her to the bathroom so she wouldn’t get lost.

Maryland, having dealt with his father’s dementia, began sharing the wisdom he’d gained along the way.

“I’d bring Larry over and he’d be watching me, observing how I care for him [Carl], how I wash him up and all that. Just different techniques,” Maryland says.

He’d also share supplies, including diapers as Dalton’s girlfriend began forgetting how to go to the bathroom. At first Dalton was squeamish about such matters, as he’d never even seen her relieving herself during their long relationship. He got over that and learned to approach such moments clinically.

Beyond the financial burden, the demands of caring for someone with dementia can significantly impact caregivers’ mental and physical well-being. This can manifest as heightened stress, depression, exhaustion, compromised self-care, physical discomfort, feelings of guilt, and strained social relationships. While they admit the task is taxing, most family caregivers of color balk at what they do being called a burden. They often have a different perspective, approaching caregiving as an honor and a privilege while some look at it as a sacrifice or burden.

About 30% of caregivers are themselves 65 or older. Maryland turns 62 in January and Dalton is 73. They’ve had to oversee an adult’s day-to-day care while trying to stay healthy enough to be up for the task. They have aches and pains related to their own aging.

Dalton has had a knee replacement and tries to get to the gym when he can. Maryland still finds time to play basketball with friends and even rollerblades on occasion.

“I’m just trying to focus on me, body-wise, to get my body in shape mentally, spiritually and physically,” Maryland says.

He does it not for himself, he says, but for his father.

“I just want him to have the best life, a peaceful life, really.”

In 2022, the Family Caregiving Institute at the Betty Irene Moore School of Nursing at UC Davis joined with the Family Caregiver Alliance and California Caregiver Resource Centers for a study on California’s caregivers. Participants reported more adverse physical and mental health effects from their caregiving role, including isolation and loneliness. During the second year of the project, 90% of those surveyed were providing complex and intense care. It’s care that most aren’t trained for, says Carmen Estrada, executive director of the Inland Caregiver Resource Center in Southern California.

“Caregivers are really the backbone of our health care providing care for our older adults,” Estrada says.

The UC Davis study found that 73% of respondents spent more than 40 hours per week providing care for loved ones and that Black, Hispanic and Native American caregivers spend more time providing care with fewer resources.

Adult sons and daughters often speak of the role reversal of caring for aging mothers and fathers who no longer can do for themselves, feeling as if they’re now the parents. Being there for his dad is particularly poignant for Maryland, who, as an infant, was cared for by Carl while his mother went back to work.

Robert acknowledges his father wasn’t always easy to live with. He remembers him as a “loud and opinionated” man who was extremely private, rarely showed emotion or talked about his past. Carl was different as a grandfather, Robert says.

“He taught me not to yell at my girls,” he says. “He taught me to be a better dad.”

EDITOR’s NOTE: This article is part of OBSERVER Senior Staff Writer Genoa Barrow’s series, “Senior Moments: Aging While Black.” The series is being supported by the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism and is part of “Healing California,” a yearlong reporting Ethnic Media Collaborative venture with print, online and broadcast outlets across California. The OBSERVER is among the collaborative’s inaugural participants.