Beyond Policies: A Closer Look at Undocumented Asian Lives

The story was co-published with World Journal as part of the 2025 Ethnic Media Collaborative, Healing California.

US-Mexico border in Jacumba Hot Springs, San Diego County. Jian Zhao/World Journal

In a country shaped by generations of immigrants, millions now find themselves living at the margins, as immigration enforcement tightens under the Trump administration. Among them are a growing number of undocumented Asian immigrants, many caught in legal limbo — unable to adjust their legal status, return home, or speak openly about their lives.

Many people question why some Asian migrants don’t immigrate legally like others do or choose to stay in the U.S. without legal documentation. The reasons vary. Some seek asylum, while others long for better work and educational opportunities that are often lacking in their home countries. Yet as immigration debates continue to rage, the voices of undocumented immigrants themselves remain faint.

Who are they? The real people behind the headlines

Fifty-six-year-old asylum seeker Yuan Yang came to the U.S. from China in 2011 and, unable to afford an immigration lawyer, has been handling his immigration case on his own. His application has never been approved, and his work permits were rejected six times, according to the immigration documents he shared. Over the years, he worked in restaurants, as a day laborer on home renovations, and most often cared for the elderly. Years have passed. Now, older and without a work permit, he cannot find a job to support himself. As he evaluates his life and considers his choices, he’s begun to despair. “I’m desperate and regret coming to the U.S.” he said. But going back is no longer an option — there’s nothing left for him in China.

Unlike Yuan Yang, 79-year-old Lily Li said she has no regrets, despite missing her final moments with her mother. She spent the last 18 years in the U.S. sending money home to support her elderly mother and her medical treatment. Her mother passed away in 2022, and Lily decided to remain in the US to save enough for her own retirement. Over the years, she has worked as an in-house nanny for several families, earning under $2,000 a month. “I’m lucky. The families I worked for treated me well, and I didn’t have to pay for living expenses,”she said.

Li pays $450 rent for a single bed in a room shared with two others. This is her corner of the room. (Courtesy of Lili Li)

Chinese attorney David Liu, based in the San Gabriel Valley, mentioned a case that left a lasting impression on him. An undocumented migrant came to the U.S. to support his family back in China, choosing to settle in Los Angeles partly because he hoped to see the ocean. After arriving, he worked multiple jobs a day. Three years later, he died in an accident while driving his truck. His wife, whose visa had been denied, couldn’t come to the U.S. to collect his body. She asked one of her husband’s friends to scatter his ashes in the ocean. He had never made it to the beach.

“This reflects the lives of many undocumented Chinese immigrants — they work nonstop to support their families,” Liu said.

People who choose to enter the U.S. without documents aren’t always seeking to escape poverty or political oppression. Lin and his wife, in their 40s, told the World Journal when they arrived at the southern border that they paid $200,000 for a safe crossing across the border into the United States because they wanted a better educational environment for their 8-year-old son with ADHD, who had experienced discrimination at his school in their home country. They said they had applied for a visa twice but been denied both times, and so decided to forego legal immigration options. As the Lins tearfully shared their story, their son silently squatted beside them, scraping the sand on the barren borderland.

The Lin family in the U.S.-Mexico border. (Jian Zhao/ Wolrd Journal)

Long Backlogs and Waits

Becoming a legal immigrant in the US requires luck and patience.

The U.S. immigration system limits the number of green cards issued annually to individuals from any single country. These country caps have led to significant backlogs for countries with high demand, such as Mexico, China, India, and the Philippines.

According to the latest Visa Bulletin from the U.S. Department of State, which provides monthly updates on when individuals can move forward with their immigrant visa applications—the step before receiving a green card—the longest wait for Chinese applicants is for those who applied before August 1, 2007.

“That is an 18-year wait to be reunited!” said Sin Yen Ling, director of communications from Chinese for Affirmative Action, an advocacy group that works to promote civil rights and social justice for the Chinese American community. She explained some people can't wait that long so they attempt to migrate through the Southern Border, and ask for asylum. Then these desperate legal cases are often rejected by immigration courts. Still, in an effort to stay in the U.S., they choose to appeal. After years of litigation, they ultimately lose and are ordered deported. But they can’t afford to leave, fearing they won’t be allowed to return.

If a U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services officer determines that an applicant is ineligible for asylum and appears to be inadmissible or deportable, they will refer the application to the immigration court.

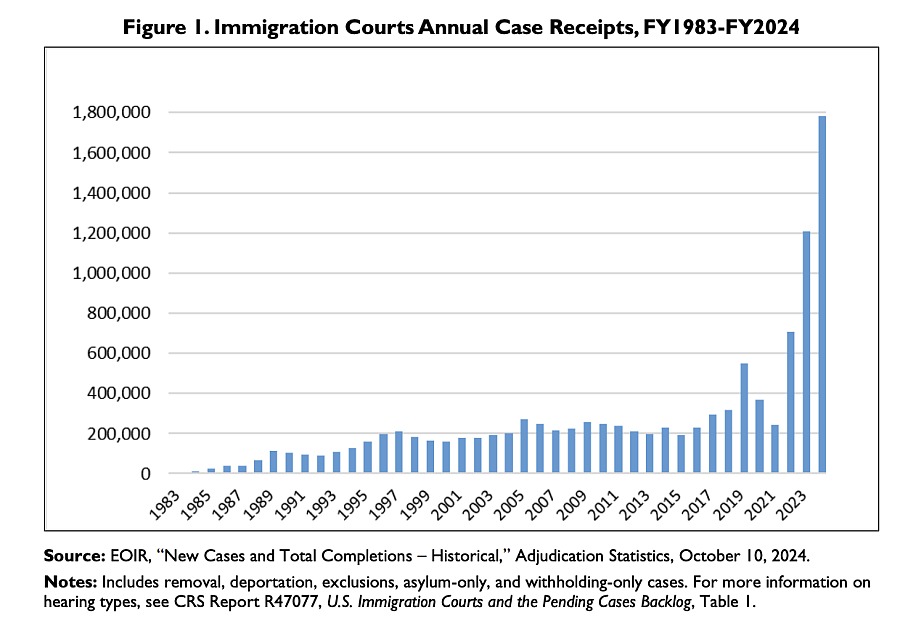

In the past three years, immigration courts have had record backlogs. which reached 3.6 million cases at the end FY2024. Many of those in removal proceedings have filed applications for asylum as a defense against removal.

Data from the Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse reveals that court records for October 2024 show only 35.8% of asylum claims were granted.

No Way To “Get in line”

Many undocumented individuals have no line to wait in.

Yudy, who has been undocumented for 20 years, shared her story through a recording with Chinese for Affirmative Action and requested that her last name be withheld to protect her identity. She came to the U.S. from Hong Kong when she was 17 because her aunt was living here.

Yudy said that at the time she did not understand what "undocumented" meant or the challenges that came with it until she was a senior in high school and applying for college. She realized she was not qualified for financial aid and had to stop her studies because she couldn’t afford tuition as an international student.

Over the years, Yudy said she has been taking low-wage jobs. “I had no choice. I had to do it because it was the only way for survival,” she said.

In 2012, Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) was created by the Obama administration to give temporary protection from deportation and work authorization to those like Yudy who had entered the U.S. as children.

“However, I missed the eligibility requirement for DACA, because it required that I be under 16 when I entered,” she said.

Another Chinese immigrant, who also requested her last name be withheld , said she entered the U.S. through the southern border in 2014 and later married a U.S. citizen. However, her husband could not petition for her because she was deemed “inadmissible” under immigration law, as she was not inspected by CBP at the time of entry.

Last year, the Biden administration sparked hope for people in her situation with the Keeping Families Together initiative. The new parole process aimed to recognize the plight of 500,000 undocumented individuals married to U.S. citizens who are unable to adjust their status. However, just two months after it was introduced, the court struck down the program.

"I am back to where I was before—undocumented but still legally married to a U.S. citizen," she said.

No Way Back

An estimated 6.3 million U.S. households include unauthorized immigrants, and almost 70% of these households are “mixed status,” with lawful residents in the family. About 4.4 million U.S.-born children under 18 live with an undocumented parent, according to Pew Research Center.

Yudy said that the rest of her family later immigrated to the U.S. through legal means. For a time, they tried to help her adjust her legal status, but this ended up exposing her situation, and she received a deportation order.

“During that time, I was so terrified of being kicked out of the U.S. All my family is here, and I don’t know anyone in Hong Kong,” Yudy said.

Undocumented immigrants who enter the U.S. without being legally inspected are generally not eligible to obtain green cards while still inside the country, according to the American Immigration Council. Even if a visa is available, they are barred from converting their status to legal one without first leaving the country, and for those out of status for over a year, there is a 10-year reentry ban. Although there are waivers that can allow people to return sooner, they are difficult to obtain. Risking a decade away from their families or established lives is too high a price to pay.

Jose Ng, one of the operators for Rapid Response Network hotline in San Francisco, which responds to people affected by recent ICE raids and detentions, said that many people arrested since January have reported receiving a deportation order.

Ng said most of the clients his organization works with have lived in the U.S. for at least10 years, and they might have a family member willing to sponsor them or help them adjust status, but they are afraid of never being able to come back.

“With families and jobs to support, it's really hard for them to leave their loved ones behind, especially those with young kids or newborn babies.”

Undocumented presence alone is not a crime

Since the surge of people crossing the southern border after the pandemic, the narrative linking immigration to crime has become widespread.The largely spurious link is often cited by politicians and conservative pundits in recent months, amid the ongoing immigration crackdown under President Trump.

Outdated and offensive terms like “illegal alien” have also fueled the belief that increasing undocumented immigration leads to more crime, portraying the undocumented group as a danger to the community.

However, many studies tell a different story. Research examining crime rates in “sanctuary cities” like Los Angeles found no discernible difference compared to other cities without sanctuary policies. In fact, undocumented immigrants are 33% less likely to be institutionalized compared to US natives.

For immigrants, the fear of getting in trouble and being deported keeps them away from engaging in criminal activities, according to studies.

"I hope people can see us from a different perspective. Although our voices are not often heard, we are here, a part of this society," Yudy said. "We came here just to escape hardship and give ourselves and the next generation a better life. We work even harder."

This project was supported by the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism, and is part of "Healing California," a yearlong reporting Ethnic Media Collaborative venture with print, digital, podcast and broadcast outlets across California.