S.F. is Evicting Homeless Families From Shelters. Here’s What to Know.

The story was co-published with El Tecolote as part of the 2025 Ethnic Media Collaborative, Healing California.

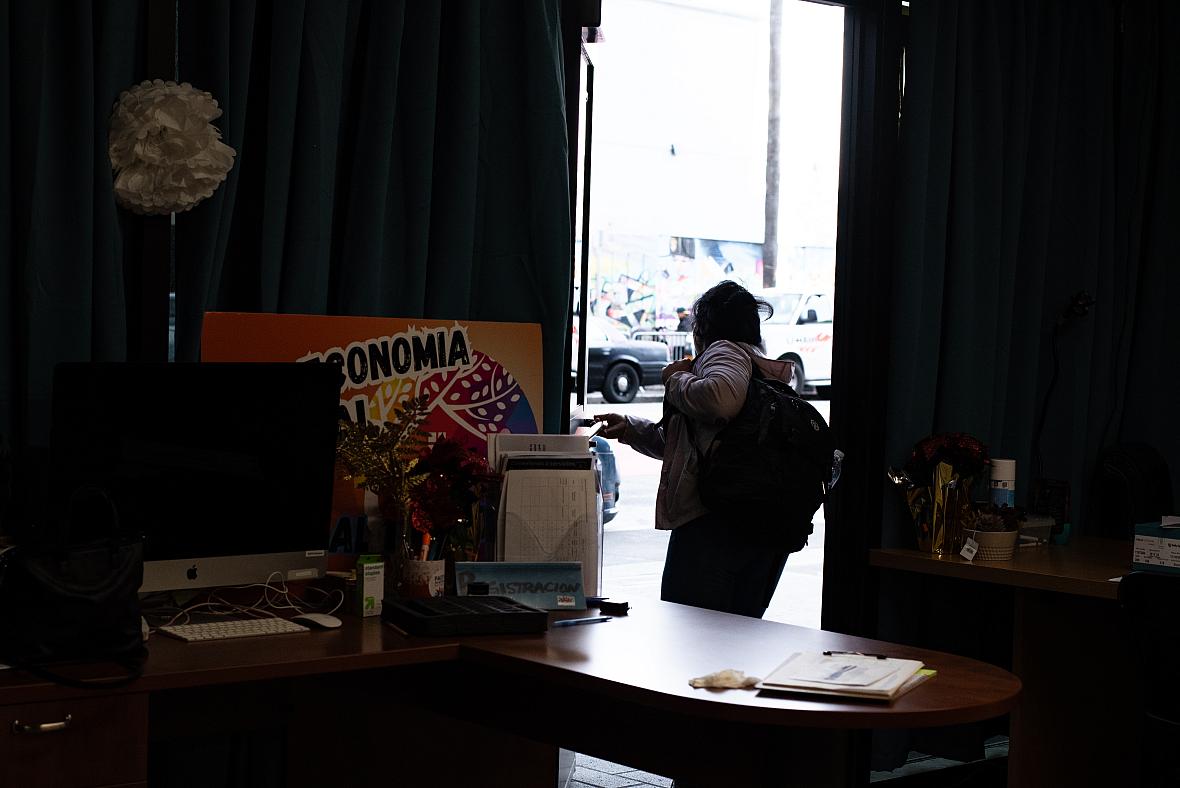

Vilma A. walks out of the Faith in Action Bay Area (FIABA) office in San Francisco, Calif. on Wednesday, March 5, 2025. Photo: Erika Carlos

At the beginning of March, Vilma A. braced for the worst. By March 10 at 5:00 p.m., she and her family were set to be evicted from a San Francisco shelter — with nowhere else to go.

Then, just hours before her scheduled eviction, she got a last-minute reprieve: a one-month extension for her family.

For the past 10 months, the Honduran mother, her husband and their two young children have lived in a San Francisco family shelter, on the waitlist for a city-provided rent subsidy that might help them afford a place of their own. Her husband, who works as a garbage collector earns enough to keep them afloat but not enough to afford the city’s high rents.

On March 7, though, Vilma said the shelter told the family they would have to leave after the weekend — whether or not they had secured housing.

Vilma was among dozens of homeless parents facing evictions this month under a controversial city policy that now limits family shelter stays to 90 days. The majority of families that were unable to secure housing, like Vilma’s, ended up receiving short-term extensions until April, but are now worried they will be in the same situation in a few weeks.

Reinstated in December, the city’s end of stay policy replaced a pandemic-era rule that let families stay in shelters indefinitely while securing housing. Now, families must apply for 30-day extensions each month after an initial three-month stay.

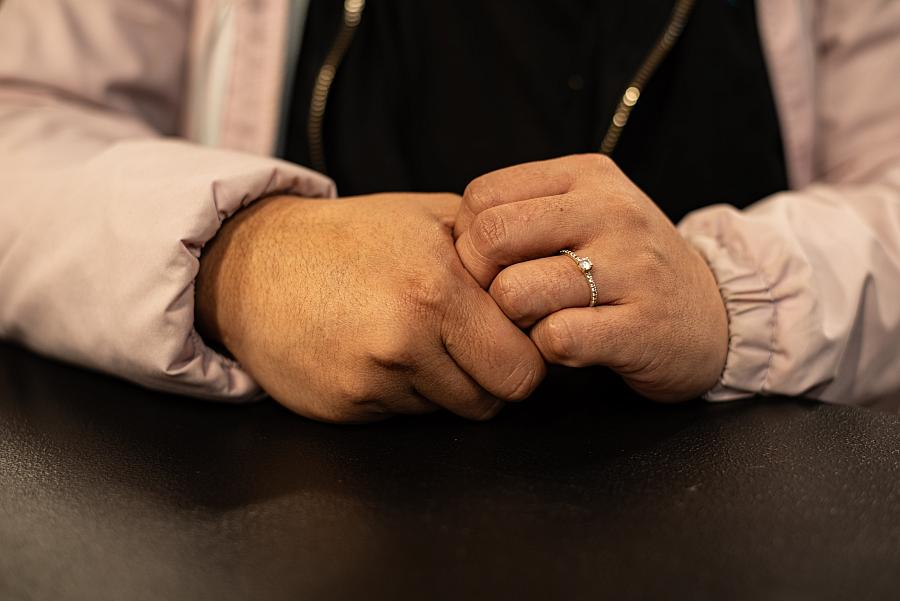

Vilma A. is one of dozens of homeless parents facing evictions this month due to a controversial city policy that limits family shelter stays to 90 days. Photo: Erika Carlos

With 318 families on the shelter waitlist, the Department of Homelessness and Supportive Housing (HSH) says the policy is meant to “increase the flow of families” through the shelter system and connect them with long-term housing solutions faster. But families say securing extensions is riddled with delays and misunderstandings, and the constant stress is taking a toll on their mental health.

“We’re trying not to get sick, to not worry too much,” Vilma said. “We know that with so much stress, people end up at the hospital. So we’re trying to take things slowly.”

Ervin M., a Honduran father, who says he has been recovering from a mishandled brain surgery, is living in a San Francisco shelter with his 12-year-old son and 64-year-old mother. Before the surgery, he said he worked for a catering company, but nerve damage impaired his mobility, making it impossible to work and to save enough to afford a place of their own.

Days before his scheduled March 10 shelter eviction, he said he was able to secure an extension, because his mother applied for a work permit. But, like Vilma, his family is reckoning with another looming shelter eviction — their new exit date is April 10.

“We don’t have anywhere else to go,” Ervin told El Tecolote.

Homeless families say they feel unheard by the city

Like Ervin and Vilma, hundreds of families are experiencing homelessness in San Francisco, a crisis that has disproportionately impacted working-class Latino households and newly arrived immigrants. The city’s Latest-Point-in-Time Count found 405 families experiencing homelessness on a given night in January 2024. Educators and service providers estimate the current number to be much higher, with more than 3,000 public school students affected by the crisis during the last school year.

Some families say they have been pushed into homelessness by medical emergencies or job losses, while others, such as newly arrived asylum seekers, have not been able to secure stable work or housing since immigrating to the city.

As pandemic-era benefits fade and affordable housing remains scarce, families who have recently managed to secure stable housing say the current process often takes several months, and on top of their income, often requires financial assistance from city programs that isn’t immediately available to everyone.

“I’m just hoping that at some point we get an opportunity to get a subsidy … an opportunity to have our own space,” said Ervin, who is worried his son is unmotivated because of their current living situation– the three family members share a room in a shelter.

Over the past year, the nonprofit Faith in Action Bay Area (FIABA) has been organizing homeless families, seeking to expand city resources available to support them. Now, the group is also rallying against the shelter eviction notices.

On Feb. 26, after more than a month of rallies and press conferences, dozens of homeless families, and FIABA advocates met with Mayor Daniel Lurie. Families at the meeting said Lurie assured them that families actively seeking housing wouldn’t be forced onto the streets.

“[Lurie] told us not to worry,” said FIABA advocate Brenda Córdoba. “We thought that meant he would mobilize, maybe talk to access points about giving all families extensions… but now he’s saying he didn’t commit to anything.”

At first, Córdoba said, the meeting with the mayor felt like a breakthrough. But when families reconvened the following week, many still had pending eviction notices. When asked to comment, Lurie’s press team referred El Tecolote to HSH.

“At the moment we’re not seeing any solutions,” Vilma said. “But we're hoping that something can happen … It’s a very frustrating situation.”

For Córdoba, this is the nonprofit’s latest frustration with city officials. Last July, after months of advocacy from FIABA, the city allocated $50 million to expand shelter capacity for homeless families, enough funding for 165 rent subsidy vouchers and 115 emergency hotel vouchers. But bureaucratic delays stalled some of it, and HSH has yet to confirm how much of that money has actually been spent.

“It’s frustrating,” Córdoba said. “Because they don’t understand what families are going through.”

Nelly, 49, and her 12 year-old son prepare their mattresses inside the gymnasium at the Buena Vista Horace Mann K-8 school that gets converted into a shelter at night in San Francisco, Calif., on Nov. 15, 2024. Photo: Pablo Unzueta for El Tecolote/CatchLight Local

Running out of time, families struggle to secure extensions

Since the policy went into effect on Dec. 10, more than 120 families have received end-of-stay notices, telling them that they must leave the shelter system by their given exit date. So far, most families unable to secure housing have been given extensions, while at least 21 have moved into permanent housing, according to HSH data.

Many families got their first end-of-stay letters in December, letting them know they would have to leave their shelters by early February. In January, HSH granted all families an automatic one-month extension, due to an update in the policy. Starting March, extensions have been up to each shelter’s discretion.

To qualify for extensions, families must work with a case manager, prove they are actively seeking housing and meet specific criteria, such as medical conditions, pending housing placements, or other barriers beyond their control, like immigration-related challenges.

Case managers must document each case, submit it for approval to the shelter, and inform families within seven days, both verbally and in writing. Extensions beyond the three months are possible but require sign-off from HSH.

Families that don’t meet the extension eligibility requirements can get back on the shelter waiting list 14 days before their exit date if they don’t have a safe place to go, HSH told El Tecolote.

Several parents told El Tecolote they qualified for extensions but were informed days or even hours before their scheduled eviction dates.

Vilma, who is currently in asylum proceedings, says she struggled to get shelter staff to understand her situation. The same day as her scheduled eviction, she shared her story in an emergency press conference organized by FIABA.

“We are in the process of securing housing,” said Vilma during the press conference. “But despite that they are not giving us more time to be in the shelter.”

Last week, HSH told other outlets it evicted three families that did not exit to housing and did not get a shelter extension, after reviewing their cases. The department granted three other families in the same situation a last minute extension – one of whom was Vilma.

Families experiencing housing insecurity line up for dinner inside Buena Vista Horace Mann K-8, a school that serves as a family shelter at night, in San Francisco, Calif., on Oct. 16, 2024. New city policies limit how long families can stay in shelters and tighten eligibility requirements. Photo: Pablo Unzueta for El Tecolote/CatchLight Local

The toll of eviction notices

Córdoba says the constant stress of looming evictions is taking an emotional toll on families. What families need from the city, she says, is more shelter and permanent supportive housing — not more restrictions on top of the ones they already face.

“A month is nothing. Ninety days is nothing,” Córdoba said. “Without work, with all the uncertainty that exists, and on top of that their immigration status… Many people are scared to go look for jobs. They’re dealing with two deportations — from their home and from the immigration status that they might hold.”

Recent studies have shown that even a perceived risk of eviction is associated with elevated mental health problems, and that depression and anxiety medication use is higher in communities at risk of eviction. Other research has found that evictions increase the probability of hospitalization for a mental health condition.

Several parents have told El Tecolote that they have experienced anxiety attacks and depressive episodes born out of the pressure from eviction notices. Maria Z., another Honduran mother who has received extensions up until April, said she goes to a shelter-provided therapist every day, to work through the stress from her family’s possible eviction.

“Sometimes the stress makes me want to stop fighting, but then I remember that my kids’ health comes first,” said Maria, who has three young children. “So I try to stand strong for them, because if I kept thinking I wouldn’t keep moving forward. I’d get stuck.”

Like Maria, Vilma says she keeps pushing forward for her children, a six-year-old and eight-year-old enrolled in elementary school.

“The people who are the most affected by these situations are children. Children are supposed to be happy” Vilma said. “It would be too much for me to tell them that we have to go to the street.”

This project was supported by the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism, and is part of "Healing California," a yearlong reporting Ethnic Media Collaborative venture with print, digital, podcast and broadcast outlets across California.